Contents

Figures

Tables

First published in the UK in 2019 by

Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2019 by

Intellect, The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street,

Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2019 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copy editor: MPS Technologies

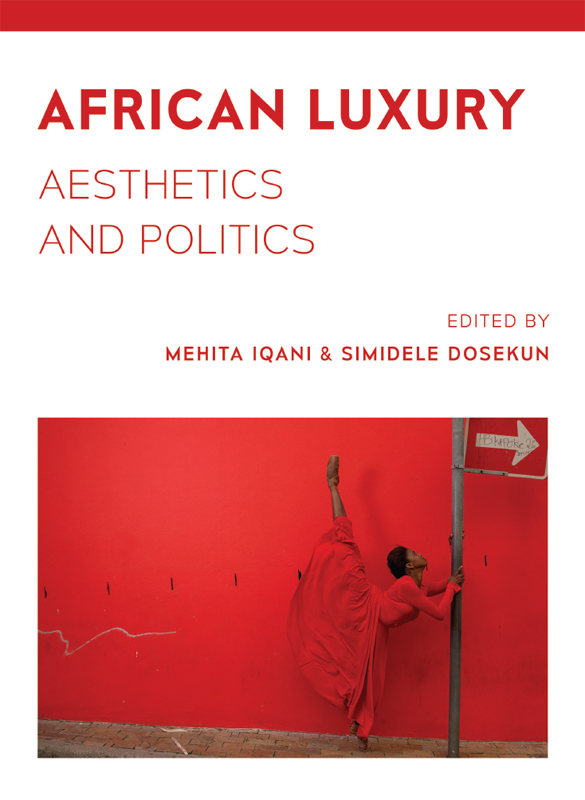

Cover designer: Aleksandra Szumlas

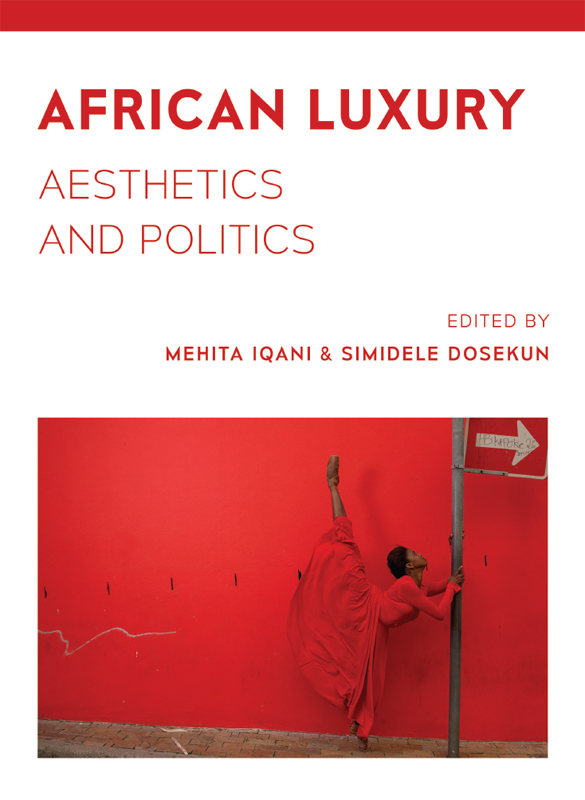

Cover image: Copyright Sydelle Willow Smith, featuring ballet dancer Londiwe Khoza.

Production editor: Faith Newcombe

Typesetting: Contentra Technologies

Print ISBN: 978-1-78320-993-4

ePDF ISBN: 978-1-78938-024-8

ePUB ISBN: 978-1-78938-023-1

Printed and bound by TJ International, UK.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND) Licence. To view a copy of the licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Simidele Dosekun and Mehita Iqani

S ome might assume that the phrase African luxury is an oxymoron, certainly not considering the notion that Africans are the consumers of said luxury. At the time of writing, entering the search keywords Africa and luxury into Google Scholar resulted not in scholarly work that engaged critically, or indeed otherwise, with how luxury consumer cultures play out in African settings, but rather in numerous articles that use the idea of luxury as a rhetorical device to ask whether certain developmental needs are necessities or nice-to-haves for Africans. For example, one question raised is whether the availability of adolescent psychiatry is a luxury for African communities (Robertson et al. 2010), and it is also considered how, in certain Aids-stricken African contexts, it might be a luxury to grieve for loved ones lost to the disease (Demmer 2007).

While there is extensive scholarship examining various aspects of contemporary consumer cultures and identities in Africa, including those of elite actors and demographics (Dosekun 2020; Gott 2009; Huigen 2017; Iqani 2015) and those centred on expensive goods and indeed their symbolic destruction, in the case of the South African township culture, izikhotane (Howell and Vincent 2014) luxury has been little considered as a distinct category thus far, moreover as distinct from conspicuous consumption. Some attention to luxury can be found in work on other global south locations often, tellingly, more in relation to so-called new middle classes than the elites or super-elites of concern in the global North (Brosius 2012; Fernandes 2006; Lange and Meier 2009; Southall 2016). There is, for example, work on luxury accommodation in gated communities in Bangalore, India (Upadhya 2009); on the growing popularity of luxury golf courses in China (Zhang et al. 2009); and on middle-class Thai consumers savvy expenditure on affordable fast fashion, complemented with substantial investments in expensive western branded goods a Prada bag, a pair of Gucci sunglasses, which gives them entry into elite consumer spaces, and which are often resold or traded at luxury goods exchanges (Arvidsson and Niessen 2015: 9; Wattanasuwan 1999). At the same time, in both the larger and more established body of scholarship on luxury from business, marketing and management studies (Cavender and Kincade 2014; Dubois and Duquesne 1993; Kapferer and Bastien 2012; Truong et al. 2008), and in the emergent field of critical luxury studies concerned with the cultural and other politics of what is contemporarily deemed luxury (Armitage and Roberts 2016; Featherstone 2014), the focus is almost exclusively on the global North.

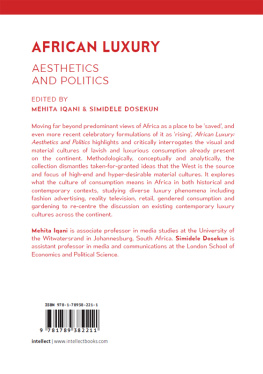

African Luxury: Aesthetics and Politics emerges from, and begins to fill, these multi-faceted gaps. With original case studies spanning the continent, from Togo to the former Zaire to Angola, the book moves beyond predominant imaginaries of Africa as a place to be saved or aided, as well as more recent, teleological formulations of it as rising, to foreground and also historicize different extant forms of the production, consumption and representation of wealth, indulgence and lavishness on the continent, including self-declared luxury brands, services and industries. We know that, however precisely defined, luxury very much matters. It matters in our contemporary global moment of extreme income inequality; in a world in which we speak routinely of not just the 1 per cent but smaller fractions thereof and, conversely, of surplus or disposable populations, the many (and rising) on the sharp end of neoliberalisms power to define who matters and who doesnt, who lives and who dies (Giroux 2008: 594). If in even the wealthiest and officially democratic of societies, food banks and Ferraris coexist in close proximity (Armitage and Roberts 2016: 1), luxury becomes a matter demanding close scholarly attention and critique.

As John Armitage and Joanne Roberts (2016: 14) write in their delineation of critical luxury studies as an emergent, interdisciplinary field one in which we situate this book luxury is a site of power and of struggle. Luxury, in the first place, is a difficult property to define and fix, being highly relative and contextual. Literally, the word points to the non-essential, to that which is desired rather than strictly necessary, although this boundary between need and want is cleverly blurred by marketers. The tag of luxury assigns considerable symbolic meaning, rendering its referents not only symbols of wealth and status but also of the consumers personality, taste and ability to access a world of exclusivity and superiority, from the craftsmanship of material goods to rarefied experiences of leisure. At the same time, luxuries are things which have power over us; by offering a range of pleasures they sway and move us (Featherstone 2014: 48). Luxury can serve, then, as a site and method to pose and answer critical questions about power. Through luxury we can trace, theorize and, in and across divergent sites, connect the complex political-economic, social, cultural and also subjective workings of global neoliberalist capitalism. Luxury points our attention to the sensory and affective, too, including as newly intensified realms of commodification and economic value (Bhme 2003).

From African and other global southern perspectives, luxury also matters and reveals, because the inequalities that enter necessarily into its meanings and marks centrally include the geopolitical. A key question that arises is the extent to which the very idea of luxury today, as well as the kinds of brands and commodities most associated with it, are wedded to ideas of the global, and the western more specifically, such that global luxury economies can be considered new sites and vehicles of cultural imperialism. A cursory observation of elite consumer practices and tastes in key African cities might seem to confirm the cultural imperialism thesis: what we see most typically and visibly construed as luxury includes French champagne, Italian suits and fashion labels, American-style malls, German sports cars, private jets and the like. In recent years, western media outlets have also begun to see and take an interest in African elites and their spectacular consumption, often focusing on their travels to, and lifestyles in, the West often in a patronizing and scandalous tone. The Nigerians have arrived declares a 2014 article in