David Shneer - Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph

Here you can read online David Shneer - Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190923815

eISBN 9780190923839

All photographs unless otherwise specified are courtesy of the Dmitri Baltermants estate, Glaz Gallery, and Paul Harbaugh.

I first saw the print hanging in a local photography collectors basement. It was 2003, and I had been connected to this mysterious collector by Simon Zalkind, my next-door neighbor and a local curator, who knew I was in search of great Soviet war photography for a book about Soviet Jewish war photographers that I was working on.

Do you know Paul and Teresa Harbaugh? If not, you should, he said.

A five-mile drive away, I was greeted at the door by a tall, silver-haired gentleman, a classic image of a patrician American, and his wife, Teresa, a feisty, passionate woman proud of her Lebanese heritage. We descended into their basement to see what would turn out to be one of the largest collections of Soviet photography in the world. The basement is Pauls workspace, cluttered with bric-a-brac and valuable photographic material. (Teresa had a separate workspace down the road at their business, Azusa Publishing, before her untimely death in 2016.) He stored his best material in the laundry room.

Come in here and take a look, Paul said as he pulled out large prints and laid them flat... on the washing machine. He began showing me massive-scale prints by a whos who of Soviet photography, names who at the time were barely recognizable but who would become intimately familiar to me as I worked on my bookYevgeny Khaldei, Georgi Zelma, Mark Markov-Grinberg, Arkady Shaikhet. They pictured everything from soldiers waving flags over the Reichstag and tanks plowing through the snow in Stalingrad to gruesome images of concentration camps at Stutthof and bodies being dragged on a sleigh through the streets of Leningrad during the siege of the city. And then he paused. This one is special.

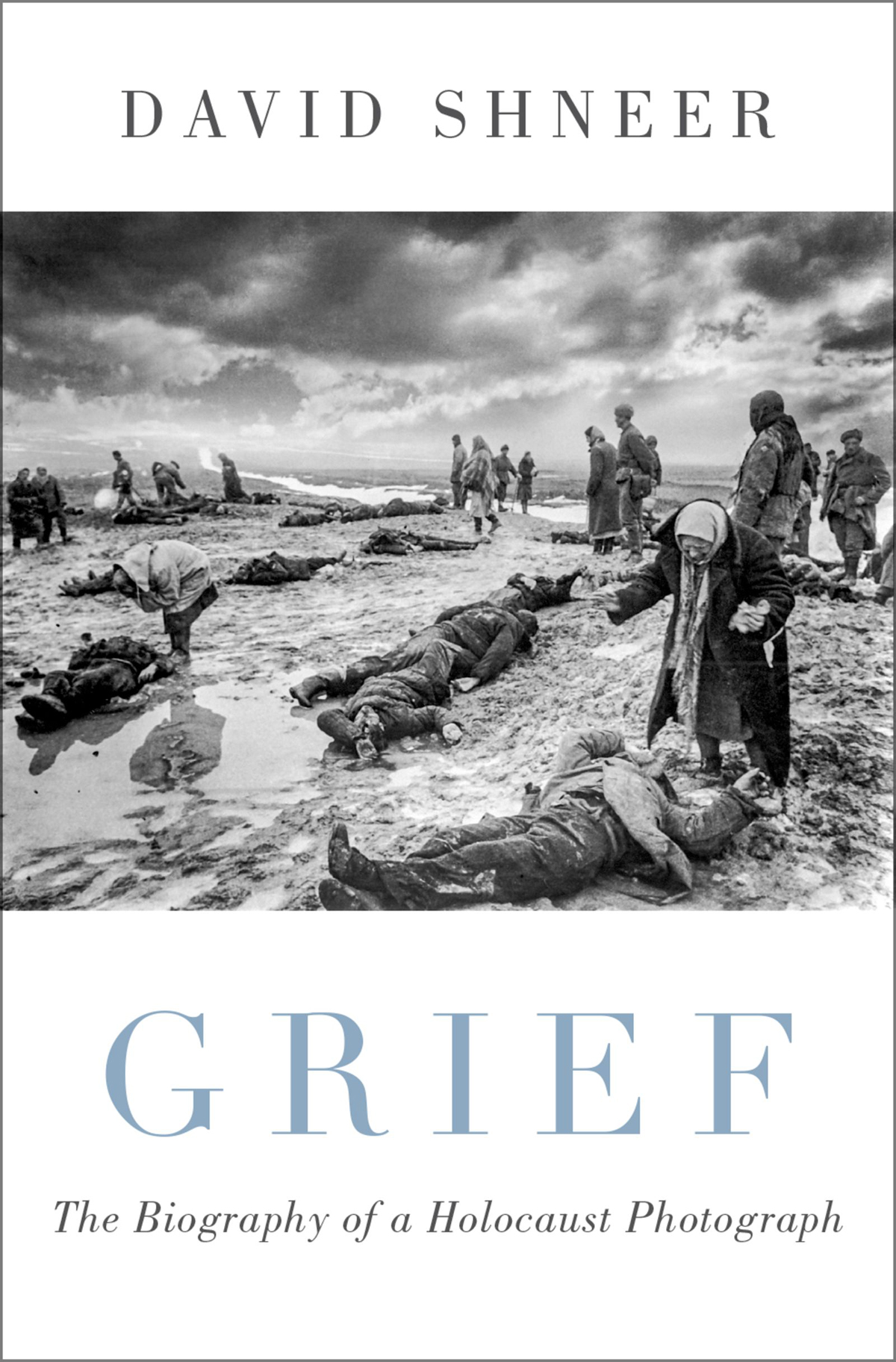

I had never seen anything like what he was showing me at that moment. First was its sheer scale: it was bigger than most photographs from the era, a limited-edition exhibition print measuring approximately thirty-six by forty inches, printed on heavy, glossy paper. But it was not just the sheer size of the image. Dark clouds hang over the scene, ominously, almost as if they had been placed there to lend the scene a dark air of horror. The sky takes up the top third of the picture, but then my eye was drawn to the woman in shock and sorrow. At first I thought she was alone, as if the photographer had chosen her from among all the others, to capture the expression of a woman discovering her husband lying dead in that snow-covered field. The addition of the dark clouds drew me into the image, a way of using perspective that created empathy between the viewer and the subject, whose name I would later learn was P. Ivanova.

Paul then explained that the photographer, Dmitri Baltermants, had been on a field in the southern Soviet city of Kerch to document the aftermath of battle in January 1942. He documented this horrible scene and called it Grief. He said that the photograph was suppressed during the war so as not to lower the morale of the Soviet population any further than it already had been in those dark years when the country nearly fell to Nazi Germany. The image made its debut only in the 1960s, during the Thaw, when Nikita Khrushchev finally forced the country to confront the violence of Stalinism.

I stared at the photograph for several more minutes, and I began to notice that the woman was not alone. In fact, Baltermants photographed a whole series of women discovering their loved ones on the battlefield, or so I thought at the time. The photograph clearly resembled classic postbattle imagery, such as the Civil War photographs of Mathew Brady, taken at a time when postbattle images were the only kind of war a photographer could capture. By World War II, photographers no longer lugged around huge amounts of heavy equipment, as Brady did. During World War II, such photographers became photojournalists with lightweight portable cameras, albeit still developing their photographs in makeshift darkrooms on the battlefields, like nineteenth-century war photographers. But by World War II, they sent their negatives and notes about the photographs to their editors on airplanes for possible publication.

I was struck by the amazing, ominous sky. How did Baltermants manage to take photographs of horror on a day when the sky so naturally lent itself to such a scene? I asked.

He didnt, Paul replied, as he then explained how Baltermants had collaged two prints together because of damage on the original negative sometime after Joseph Stalins death, when the photographer began playing around in his archive and then gave the composition its title.

Since that day in 2003, I have seen prints of Grief, whose original Russian title was the similarly laconic Gore, in dozens of places: hanging in galleries in places as far flung as Moscow, Paris, and Berlin and on the sterile white walls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. I saw it at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles in an exhibition dedicated to war photography, where it served as one of the signature photographs. It is also one of Time magazines one hundred most influential photographs in the history of photography. Sometimes, Grief stood alone, as if it needed no context to explain what was happening in the picture, just the tombstone label: Dmitri Baltermants, Grief, 1942, Kerch, Silver-Gelatin Print, Collection of Teresa and Paul Harbaugh. On other occasions, the exhibitions curator hung Grief alongside other photographs to create a visual dialog, juxtaposing it with others that Baltermants took at Kerch or other photographers images of war. But for the most part, the curators choices suggested that the image speaks for itself.

After years of researching this image, I have still never seen the damaged negative of the Grief photograph. I came close one afternoon in 2008 when I was working in the Baltermants archive in an attic in Scarsdale, New York, at the home of Michael Mattis, a second collector involved with Baltermants and his estate. Mattis had purchased the Baltermants archive, some thousands of negatives in all, in 1999 and hoped to turn a little-known Soviet photographer into the next Robert Capa. He showed me the massive amount of work his research assistants had done cataloguing, labeling, and putting into archival envelopes each and every negative. That day, however, he could not find the negatives from Baltermantss photographs at Kerch. Then, in 2010, as I later learned, he sold the archive back to an investment group in Russia and the negatives have since seemingly disappeared.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph»

Look at similar books to Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Grief: The Biography of a Holocaust Photograph and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.