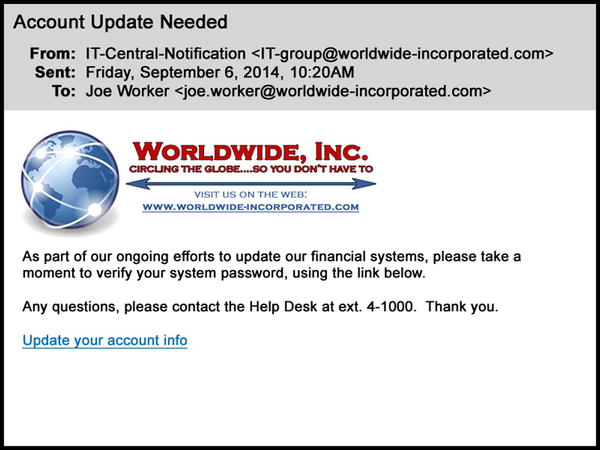

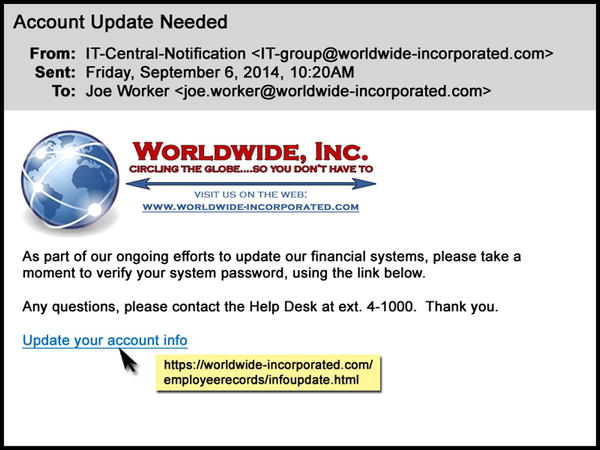

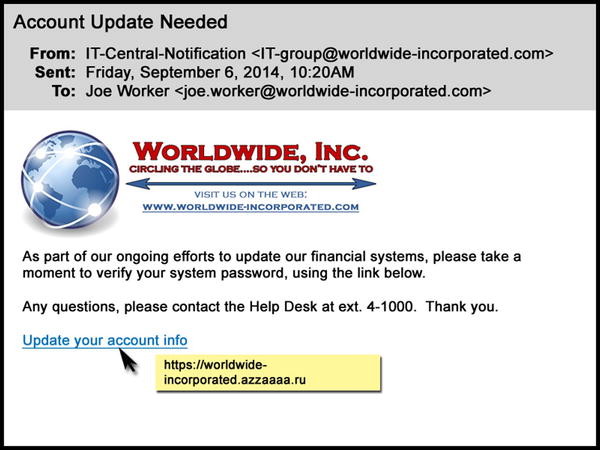

Joe is a midlevel procurement manager with 14 years of experience at the multinational company Worldwide, Inc. His section is a large one, and much of the procedural updating that regularly comes through official channels is disseminated virtuallyby text, the corporate instant messaging application, or e-mail. Joe rarely sees his immediate supervisor during the course of an average day and is accustomed to gettingand followingelectronically delivered policy and housekeeping directives. Joes communications with administrators from other sections in his division also typically come through company e-mail. From time to time updates to the companys IT systems require him to change his existing passwords or create new ones, so he is not uneasy when he receives a routine e-mail from his companys IT group directing him to update his system password (see Figure ).

Figure 1-1.

Sample e-mail asking for password confirmation and featuring two hyperlinks: the company logo and the Update your account info line

The e-mail is fairly well-written and looks kosher. It employs quasi-proper English grammar, incorporates the company logo in the usual way, and is signed with the correct phone extension for the IT help desk. The message contains a hyperlink to the companys web site and another for Joe to confirm his existing password and set a new one.

A Closer Look at Phishing

Phishing is a virtual attack that uses a more or less compelling or attractive lure to acquire confidential or proprietary information through the use of fraudulent electronic communication. Victims of phishing attacks get caught when they take the bait offered by a phisher, such as an apparently legitimate request by their IT department to change a password or by their credit card company to protect an account with an additional personal information gate. E-mail is the most commonly used approach to launch a phishing attack, but such attacks can also be launched through web sites, text messages, IM (instant messaging), and mobile apps. Phishing techniques began to be deployed in the late 1980s, some years before the term itself was coined. The term derives from fishing for gullible users login credentials and personal details, orthographically tweaked by substituting f with ph by analogy with phreaking (the practice of cracking phone network security to make free long-distance calls). The phish most commonly seen by IT departments is the one that almost snared Joe in the opening scenario. An electronic communication is sent to a target with a link embedded in a message that looks official but in reality originates from a fraudulent party seeking to steal personal information in order to gain malicious access or to resell to a criminal cyber organization.

Phishing techniques are increasingly sophisticated and well-crafted. No longer are incongruous language, improbable scenarios, or misaligned layouts used that give off the stink of phish that is immediately obvious to any employee. Today, the word choice, spelling, and grammar deployed in the most dangerous class of phishing messages are correct or, even better, are calibrated to be just slightly illiterate, in the same way that genuine corporate communications tend to be (as in Figure ). Such phishes blend company logos, colors, design schemes, and other attributes of official communications in mimicry of legitimate messages that employees and customers routinely receive. Their sending e-mail addresses and hyperlink URLs are typically spoofed to resemble those of legitimate senders.

Sophisticated phishing operations are adept at securing and exploiting information about companies internal changeover periods. If a company is in the process of undergoing IT system changes of any kind, its users are more likely to expect rather than suspect password change requests and other change-associated e-mails. Phishers prefer to time their attacks to correspond with periods of transition when users psychological defenses are temporarily relaxed.

The majority of phishing attacks are long-line or . These attempts dont have a specific target. Their goal is to snare as many victims as possible following a volume or economies-of-scale approach and leveraging a broad, randomized targeting scheme. Contrasted with this kind of broadcast phishing is spearphishing , which is carefully and lethally aimed at a specific individual, company, school, or other organization. These kinds of attacks are much more dangerous than conventional untargeted phishing scams.

Target-ed Phishing

A targeted spearphishing attack may be deployed to go after someone specific, such as Joe, because the attackers are aware that he has a system account with access to sensitive company information. A general, untargeted phishing attack may go out to literally tens or hundreds of thousands of mailboxes or phones. If even a few of the targets click on the malicious link, the attack is a success. Spearphishing attacks, on the other hand, target a defined group of users or even only one high-value user within an organization.

One of the troubling characteristics of contemporary phishing is the range and versatility of tactics attackers use to lure or lull victims into providing valuable information. For example, in phone-keypad phishing, users are told to dial a number that a caller says belongs to the end users bank or credit-card company but that is in reality owned by phishers. End users enter their account number, social security number, PIN code, or other private information via the telephone keypad, which is then captured and sold or used by the phishers.

Phishers use cross-site (CSS or XSS) to compromise legitimate sites with pop-up windows or browser tabs that redirect users to fraudulent web sites. CSS attacks are more prevalent on computers and systems with unpatched and/or outdated operating systems (for more, see ).

Neutralizing phishing is not a trivial issue. Whats at stake? Money. Most phishers are in it purely for financial gain. EMCs 2013 annual report estimated that $5.9 billion was lost worldwide to nearly 450,000 phishing attacks. This same report identified a hacking tool called Jigsaw that allows malicious actors to gain specific and detailed employee information for use in spearfishing attacks. With access to your bank account information and password, phishers can easily transfer funds away from your accounts or divert a paycheck or other direct deposit away from your account to accounts that they control.