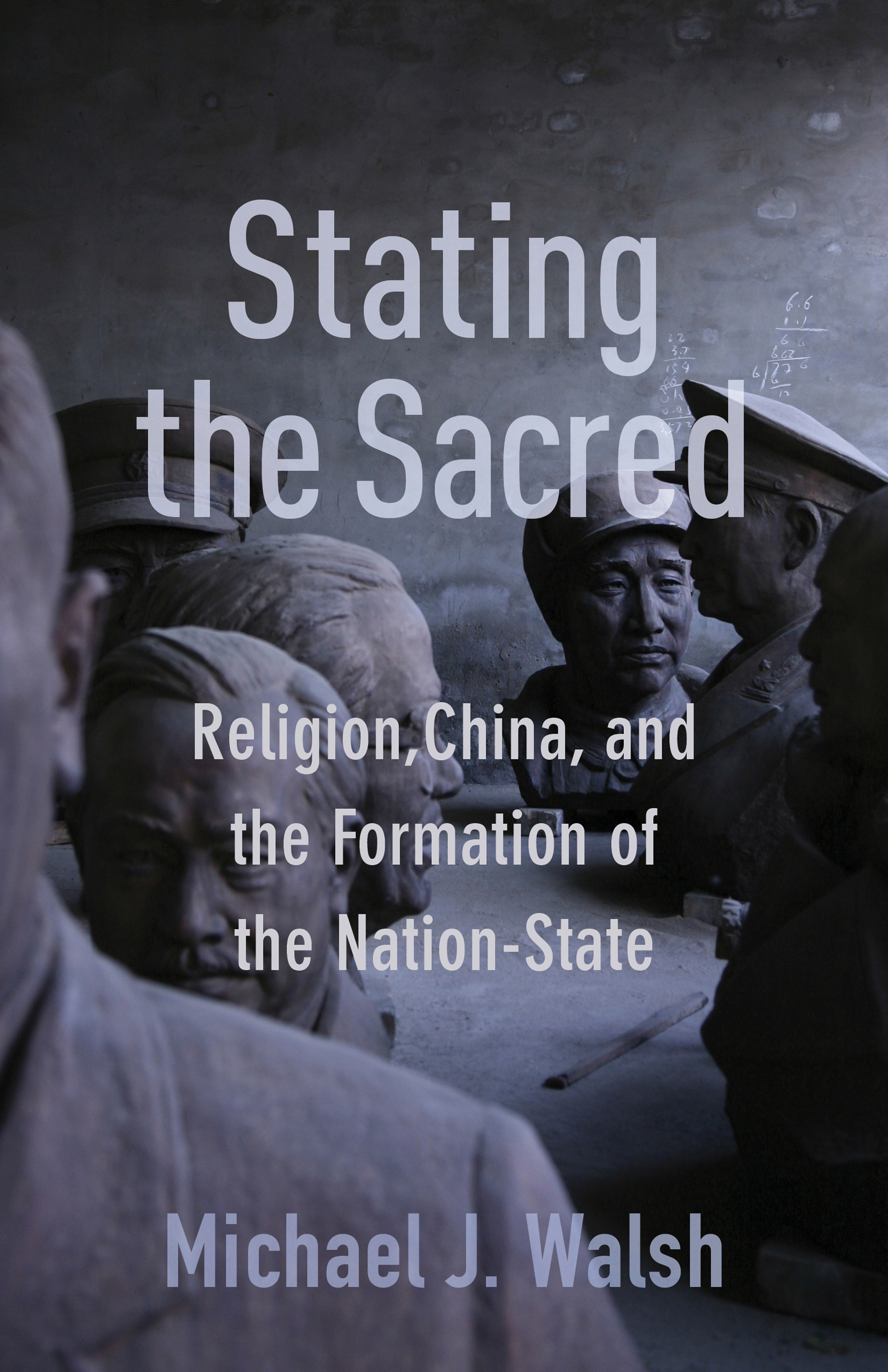

Michael J. Walsh

Names: Walsh, Michael J. (Michael John), 1968 author.

Title: Stating the sacred : religion, China, and the formation of the nation-state / Michael J. Walsh.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019023904 (print) | LCCN 2019023905 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231193566 (cloth) | ISBN 9780231193573 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Civil religionChina. | Religion and stateChina. | CitizenshipChina. | National characteristics, Chinese. | Nation-state

Classification: LCC BL1803 .W25 2020 (print) | LCC BL1803 (ebook) | DDC 322/.10951dc23

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

I n 1989 the campus at the University of Cape Town was a space of violence. As students protesting the apartheid regime, we faced regular clashes with the police, our ears and bodies threatened by the sound of bullhorns, shotguns, tear gas, and sjamboks. On the streets, in the cities, the police began using a special purple dye fired through water cannons. It stained the skin for days. They could then arrest and detain at will. South Africas own purple rain.

No amount of purple could erase the black, brown, and white skins on their return to campus. The state was dying, and we wanted a fiery revolution that could eradicate a history. Nelson Mandela had a different plan. You have five minutes to disperse! yelled the policeman through his megaphone. And we did feel dispersed. We would read in the newspapers the number of people killed in the townships the day before, then go to our next class. At first the dead numbered in the hundreds and then the thousands. Black smoke from burning tires filled the township horizons. Time to picket the main freeway that snaked below the university campus, making its way into downtown Cape Town.

We would attend a political rally, then attend to our studies. Yet we did not know at the time that apartheid was falling apart; that the violence we were witnessing was the final crescendo at the end of a fireworks display. A state was coming to an end, and a new nation was going to have to be imagined. Amandla! (power) was the call for resistance. Awethu! (power to us) was always the reply.

I took a seminar and an independent study that year that helped me think about the state we were in, about politics and the sacred, violence and Christianity. (The apartheid government spoke with a God on its side. The rhetoric of a chosen white race and divinely bestowed sacred land went hand in hand.) The seminar was with David Chidester, who introduced me to the interdisciplinary endeavor of religious studies. I sat in his office one afternoon, pointed at his bookshelves, and asked him what my students now ask me: Have you really read all these books? He said he had and then grabbed one bookMary Douglass Purity and Dangerand told me to read it immediately.

What a remarkable study! It clarified for me the role of ritual in demarcating boundaries between what an individual or a group of people might consider pure and what they consider polluted. It gave me a sense of how social space could be purified through ritual, constructed, and fought over. It offered me a methodological lens to help focus the way I think about apartheid South Africa, the United States, and now China. It allowed me to think about how a state needed to produce itself and the violence required to do so. It helped me better understand the purification process, or better yet, the sanctification process that the South African apartheid state undertook for decades, all predicated, however irrationally, on a covenant with a biblical God at a battle called Blood River on the morning of December 16, 1838. This was to be their sacred territory, cleansed of those less than human, or later, in apartheid government language, cleansed of those who were nonwhite. Douglas also helped me understand a singular, extreme reenactment of this event.

Exactly 150 years after the battle, Barend Hendrik Strydom walked around downtown Pretoria in November 1988 shooting any black person he could see. By the time he was apprehended he had killed eight people and wounded fifteen others. That way territory can be claimed, its inhabitants can be named, and control of its people and resources can be maintained. Only then can it be called sovereign space.

This logic forms part of an inviolate, cruel core of nation-statism. It is a theos that allows, and indeed compels, Strydom to walk through Pretoria shooting black South Africans. He felt he had the right to reclaim what he understood to be his territory, his God-given right to the land.

The apartheid regime always understood that its territory was awarded to it by God. It was sacred land to do with as the regime pleased. It was part of the mythological narrative, the same narrative that explained the regimes purported racial superiority. Strydom, citizen of a proclaimed white race, had sought to defend the purity of the states territory. Race, territory, religion, and citizenshipsignatures of the nation-statewere at the heart of his identity and actions.

My independent study was with Jan Hofmeyr. He introduced me to the readings of Confucius, Mencius, and Laozi. Jannie had recently returned from a trip to the United States, and one of the books he brought back with him was Benjamin Schwartzs The World of Thought in Ancient China. Nothing could have been farther from the reality we were living in at the time, and yet thats the book we read together, along with primary texts in translation.

As we read that June about ancient China, we watched a contemporary China with more than a million of its students pouring into Tiananmen Square. A man stood alone in front of a tank. No one will tell us how many died. Tracing a line back to 1839 with the first Opium War, the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 became a pivotal moment in Chinas historical narrative that marked the start of its current form of maximalist nationalism. A new state came into being.

Years later, sitting in my living room in the United States at 8 pm on August 8, 2008, I watched on television a countdown in Beijing led by 2,008 drummers who welcomed and presented China to the world. The twenty-ninth Olympiad had begun. It was as if China was born anew, declaring to the worlds nation-states that its nation-state had definitively arrived at the center of the worlds stage. The centerChinas literal name is Zhongguo, the central territorywas where China had been for millennia, but two nineteenth-century Opium Wars, various rebellions, and the colonization of the east coast interrupted that.