Contents

FLOATING

COAST

AN ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY

OF THE BERING STRAIT

BATHSHEBA DEMUTH

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Pulishers Since 1923

THE STRAITS

Ledum, Labrador Tea, saayumik.

A matted growth beneath the most shallow

depth of snow on record in all our winters.

Pausing upbluff from the edge of ice

I broke from branches leaves to pin

Between my teeth and tongue

until warmed enough for their fragrant

oil to cleanse you from me.

Somewhere in a bank of fog

beyond the visible end of open water,

alleged hills were windfeathered

drainages venous. In routes

along the shore forever slipping

under, I am remindedin the city

one finds it simple to conceive nothing

but a system, and nothing but a world of men.

Joan Naviuk Kane

T he people of the Bering StraitBeringiahave many names for themselves. In translation, most signify that they are the true people. By the early nineteenth century, all the true peoples lived in many small nations. The term nation is imperfect, but captures the political autonomy, territorial sovereignty, and social distinctions that ordered peoples lives. These nations came from three major linguistic groups: the Iupiat (adjective and singular, Iupiaq), the Yupik, and the Chukchi. This book uses those terms to refer to each people in general, and Beringian when referring to the three groups at once.

Everyone else is a foreigner. This term is deliberate: not all foreigners were racially white or ethnically European. Many were never settlers. In Alaska, not all were American by citizenship, just as in Eurasia not all were Russian by ethnicity or language. Norwegians, Poles, former African American slaves, Germans, Uzbeks, Native Hawaiians, and many others came to Beringia in the long twentieth century. What they had in common was an experience of Beringia that, at best, spanned a few generations. Most had far less. I, too, am a foreigner, and write as one.

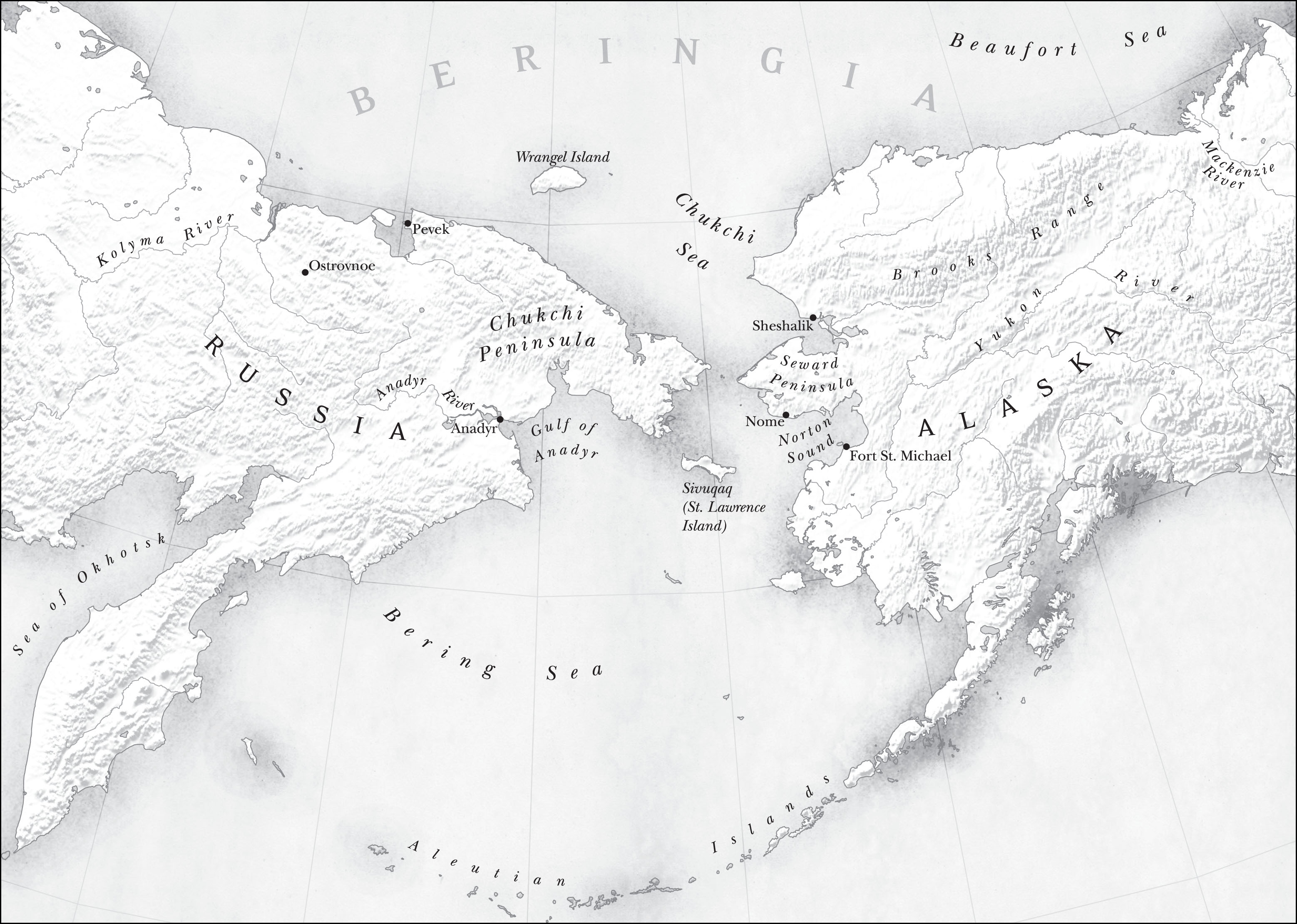

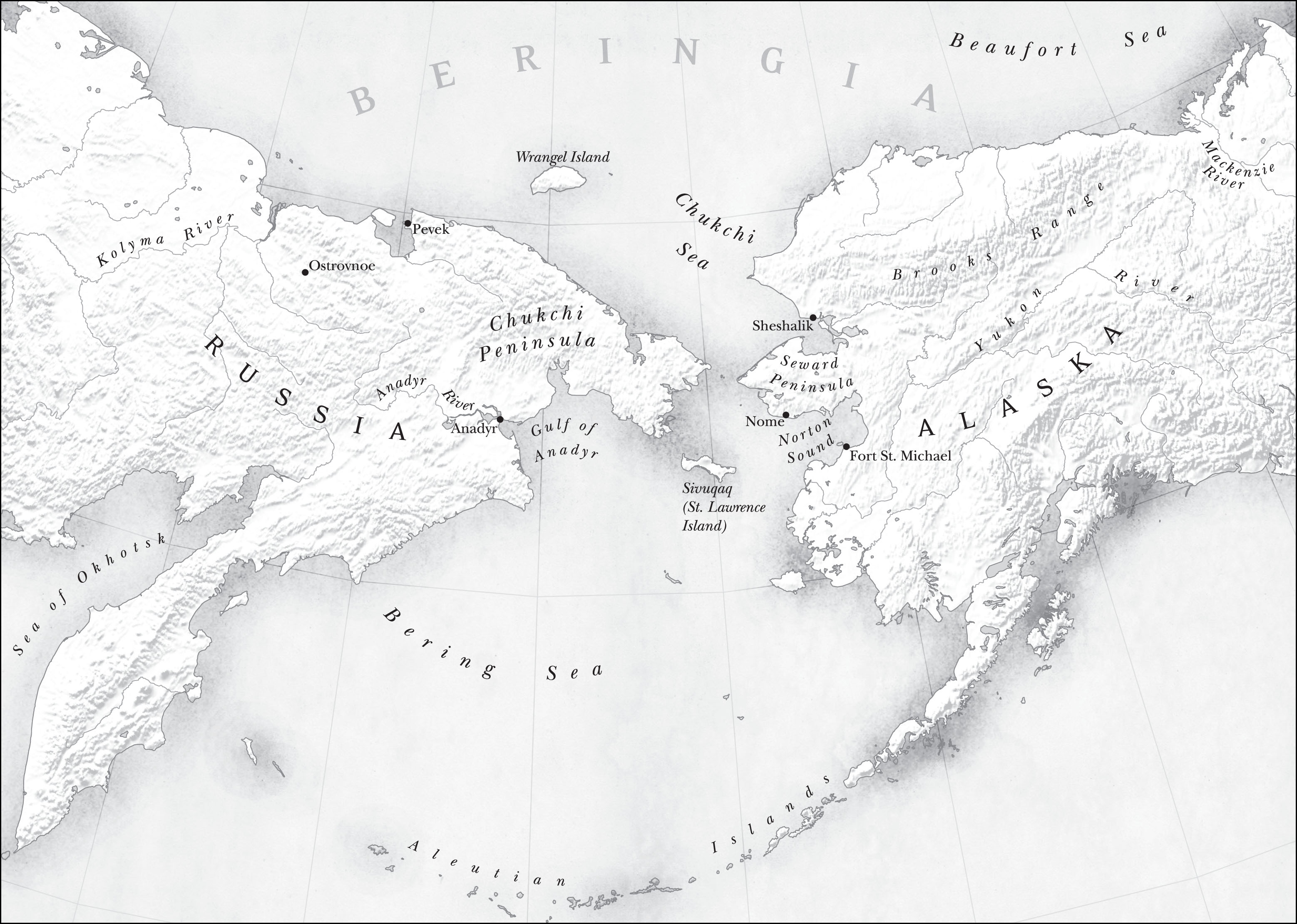

Places in Beringia also have many names. This book introduces those given by the original inhabitants first. They are replaced in the course of these chapters, as they have been on printed maps, by foreigners names. The exceptions are large regional termsChukotka, Alaska, the Seward Peninsula, the names of seas, Beringia itselfthat cross multiple linguistic boundaries. The original names will be strange to many, but then, strangeness is an experience of being foreign in a new land.

Below is a list of each original name and its colonial replacement.

| Ianliq (Iupiaq) | Little Diomede Island |

| Imaqiq (Iupiaq) | Big Diomede Island, Ratmanov Island (Russian) |

| Kiigin (Iupiaq) | Cape Prince of Wales |

| Luren (Chukchi) | Lorino |

| Qiqiktaruk (Iupiaq) | Kotzebue |

| Omvaam River (Chukchi) | Amguema River |

| Sivuqaq (Yupik) | Gambell, or St. Lawrence Island as a whole |

| Ugiuvaq (Iupiaq) | King Island |

| Ungaziq (Yupik) | Mys Chaplino (later Old Chaplino), Indian Point |

| Utqiavik (Iupiaq) | Barrow (now returned to Utqiavik) |

| Uvelen (Chukchi) | Uelen, East Cape |

| Siik (Iupiaq) | Golovin |

| Tikiaq (Iupiaq) | Point Hope |

E ach morning in spring, the sandhill cranes rise pair by pair from the fields and marshes where they rest, and turn their bodies north. They trill and honk on the wing, the sound filling the flyways of North America. By late April or May, they approach the Pacific Oceans terminus, where the Seward and Chukchi Peninsulas reach toward each other across the Bering Strait. Twenty thousand years ago, during the last ice age, the water passing beneath them was land. People hunted mammoths and caribou across a corridor of earth. Now, cleaved by just fifty miles of ocean, a geological and ecological unity remains in the territory encircled by the Mackenzie and Yukon Rivers in North America, the Anadyr and Kolyma Rivers in Russia, and the oceans north of St. Lawrence Island and south of Wrangel Island. From river to river and sea to sea, geographers call this country Beringia.

I was eighteen when I first heard the cranes, standing on the runner of a dogsled eighty miles north of the Arctic Circle, on Beringias eastern edge. I remember stopping by a lake to watch a pair dance. The light had come back, out of winter, running orange shadows onto the waning snow where the birds arched their necks, opened curtains of wing, and sang in throaty, chuckling harmony. We were both migrants from the Great Plains, the cranes and I. They came north to make from the brief fecundity of Arctic summer new feathers and new chicks. I came with less material longings: a Midwestern child raised on Jack London, I had visions of the Arctic as a beautiful but essentially static place to find nature untouched by people. My expectations were disciplined by an education that explained natures pastgeology, biology, and ecologyseparately from human history, from culture, economics, and politics. It was a divide that endowed human beings alone with the power to make change; nature was the thing acted upon.

Living in Beringia collapsed this separation. I was apprenticed to a Gwitchin musher, a task that, in its specifics, was about sled dogs, but generally required learning how not to die. I did not know, when I arrived, that moose are dangerous when startled, or where to find blueberries, or the shape of an eddy where salmon congregate, or the color of the cloud that brings the storm in the season when bears leave their dens. Sandhill season. This did not mean people did not change things. Caribou died because we killed them. Dogs were born because we wanted their labor. We lived in a village built by people, from the cabins to the diesel generator that supplied electricity and the airplanes with their cargo of bread, soda, DVDs, tools. The village, by its very existence, was a testament to how people change each other; settlement, here, was a colonial figment, brought a century before by foreigners with their ideas of law, value, and the proper way to live. But those ideas, transformative as they were, did not alter the fact that the world I ran my dog team through was dense with action and transformation, only some of it human.

My host father and his country taught me two things I have carried in the years since. The first is that if we pay attention, the world is not what we make of it; rather, it is part of what makes us: our flesh and bones, and also our inclinations and hopes. In the Arctic, such attention is not an option but is necessary, and it yields appreciation for the precarity, the contingency, of simply being. The second is a question. In the north, I saw the power of peoples ideas to change the Earthto build villages, to legislate relationships with places and animalswhile we simultaneously lived by rules whose origins were not only human. It left me wondering at the relationship between ideal and material, between human and not. What power do human ideas have to change their surroundings, and how are people in turn shaped by their habitual relationships with the world? Put another way, what is the nature of history when nature is part of what

Next page