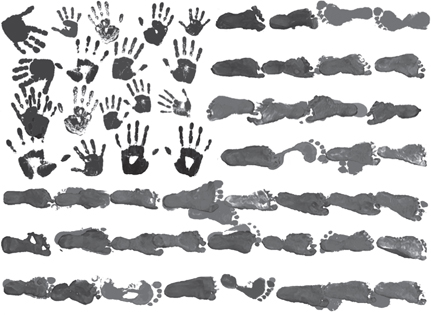

Laura Briggs - Taking Children: A History of American Terror

Here you can read online Laura Briggs - Taking Children: A History of American Terror full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: University of California Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Taking Children: A History of American Terror

- Author:

- Publisher:University of California Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Taking Children: A History of American Terror: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Taking Children: A History of American Terror" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Laura Briggs: author's other books

Who wrote Taking Children: A History of American Terror? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Taking Children: A History of American Terror — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Taking Children: A History of American Terror" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Named in remembrance of the onetime Antioch Review editor and longtime Bay Area resident,

the Lawrence Grauman, Jr. Fund

supports books that address a wide range of human rights, free speech, and social justice issues.

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Lawrence Grauman, Jr. Fund.

LAURA BRIGGS

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2020 by Laura Briggs

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Briggs, Laura, 1964 author.

Title: Taking children : a history of American terror / Laura Briggs.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020000732 (print) | LCCN 2020000733 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520343672 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520975071 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH : Child welfareUnited StatesDecision making. | Child welfareCentral AmericaDecision making. | Juvenile detentionUnited States. | Juvenile detentionCentral America.

Classification: LCC HV 6250.4. C 48 B 74 2020 (print) | LCC HV 6250.4. C 48 (ebook) | DDC 362.7/79145610973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000732

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000733

Manufactured in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to all children unjustly taken from their kin and caregivers, especially those who died in US immigration detention in 2018 and 2019 or immediately after their release:

Jakelin Caal Maquin, 7, from Guatemala

Felipe Gomez Alonzo, 8, from Guatemala

Wilmer Josu Ramrez Vsquez, 2, from Guatemala

Carlos Gregorio Hernndez Vsquez, 16, from Guatemala

Darlyn Cristabel Cordova-Valle, 10, from El Salvador

Juan de Leon Gutirrez, 16, from Guatemala

Mariee Juarez, 1, from Guatemala

The public debate about asylum seekers in 2018 and 2019 was raw. Members of the Trump administration and its supporters considered the asylum process a farce, a ruse that allowed people who transparently had no right to be in the United States to enter. Trumps people regarded them as illegal immigrants who were trying to manipulate the law by calling themselves refugees, and they complained that special rules on the treatment of children made bringing a child with you basically a get-out-of-jail-free card. They celebrated their strategy of deterring illegals by taking squalling children from their parents and caregivers, calling it zero tolerance. Womp, womp, said former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, mocking in high frat boy form the story of a child with Downs syndrome separated from her mother.

Activists and journalists who opposed the policy protested in ways that were no less emotional. Protestors held up photos of children and parents separated from each other, downloaded pirated audio of children crying in shelters as Border Patrol officers laughed at them, and carried their own babies to demonstrations. The sounds and images of sobbing mothers and babies torn from their arms were everywhere.

In all this emotion, opponents of the policy in particular were repeating a very old move, reaching directly for historical parallels. Consciously and not, they borrowed one of the most successful tactics from the movement to abolish slavery. They tried to compel any audience they could get to imagine the fear and grief that stalked children and parents at the moment they were separated from each other and for the rest of their lives. They put that vulnerability and terror alongside the ugliness of the political ends of those who took babies and children.

In fact, some critics deliberately pointed out relationships between taking children of asylum seekers at the southwest border and the histories of slavery, Indian boarding schools, Japanese internment, mass incarceration, and anti-Communist wars against civilian populations in Latin America. Lance Cooper, a Flint water activist, tweeted what became a viral image of an enslaved mother reaching for a child being carried away by a white slave trader, writing, Dont act like America just started separating children from their loving parents. DeNeen Brown wrote in the Washington Post about the parallels: A mother unleashed a piercing scream as her baby was ripped from her arms during a slave auction, she said, reviewing an exhibit that the Smithsonian had pointedly put up on the history of child taking. Even as a lash cut her back, she refused to put her baby down and climb atop an auction block. Catholic clergy and laity holding a

These kinds of activism sought to fill a void in public memory about the history of separating children from parents. One of the refrains that too often punctuated the liberal response to the policy was This isnt America. We dont separate parents and children. (Theres nothing American about tearing families apart, Hillary Clinton tweeted.) This kind of exceptionalist claim for an American moral high ground was as unhelpful as it was untrue.

On the other side, the supporters of the Trump-era border policy, including the president himself, also gave the policy a false history. Trump insisted dozens of times that the Obama administration had also separated children from parents at the border. Except that it had not. Obamas administration took pride in the fact that it detained parents and children together. It also deployed other harsh tactics against immigrants and asylum seekers; there was a reason La Raza head Janet Murgua called him the deporter-in-chief. His administration expelled record numbers of immigrants in each of the first five years of his presidency, numbers even the Trump administration did not match. It housed unaccompanied minors at military bases, detained small children and their mothers in camps, urged expedited removal for unaccompanied children without asylum hearings, and even attempted to put children in solitary confinement to punish their mothers for engaging in a hunger strike to protest their seemingly endless detention.

Trumps misstatement seemed designed to assail Democrats in order to defend his own party. What he was evading was that it was a Republican administration, George W. Bushs, that had first separated asylum-seeking parents from their children. The Bush administration, as it securitized its immigration and refugee policies after September 11, 2001, also stepped up its punishment of children. It opened the notoriously abusive T. Don Hutto Center in Texas, where children were allegedly beaten by guards, separated from their parents, and held indefinitely until the administration was forced to stop by an ACLU lawsuit. Bushs predecessorsReagan, the first Bush, and Clintonvanished into the haze beyond the horizon of the conversation, although they, too, had put immigrant and refugee children in detention camps.

As a historian, I found the deliberate attempt to sow confusion and the failure of most people to be able to fill in the blanks or correct the misinformation in the public conversation extraordinarily frustratingand surprising. For decades, I have been writing about events that were not exactly obscure: the taking of children under slavery, in Indian boarding schools, in to the foster care system as a punishment visited upon welfare mothers, in anti-Communist civil wars in Latin America, in the moral panic about crack babies, and in the context of mass incarceration. In 2012, in a book entitled Somebodys Children, I even wrote that taking the children of immigrants was the next crisis on the horizon, in the vain hope that a history book could somehow stop it.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Taking Children: A History of American Terror»

Look at similar books to Taking Children: A History of American Terror. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Taking Children: A History of American Terror and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.