Crimes of Peace

PENNSYLVANIA STUDIES IN HUMAN RIGHTS

Bert B. Lockwood, Jr., Series Editor

A complete list of books in the series

is available from the publisher.

Crimes of Peace

Mediterranean Migrations

at the Worlds Deadliest Border

Maurizio Albahari

Copyright 2015 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-8122-4747-3

To our grandparents,

travelers

before the invention of immigration.

To the life of the drowned. To whom they loved.

Ai nostri nonni,

viaggiatori

prima che limmigrazione fosse inventata

Naim precima,

putnicima

pre nego to je izmiljena imigracija

Then again, you dont divide up an empire with a

handshake.

You have to cut it with a knife.

Roberto Saviano, Gomorrah

Contents

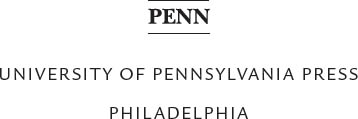

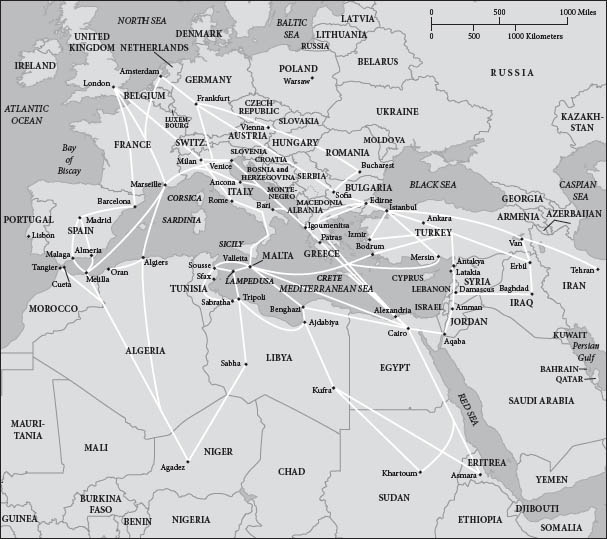

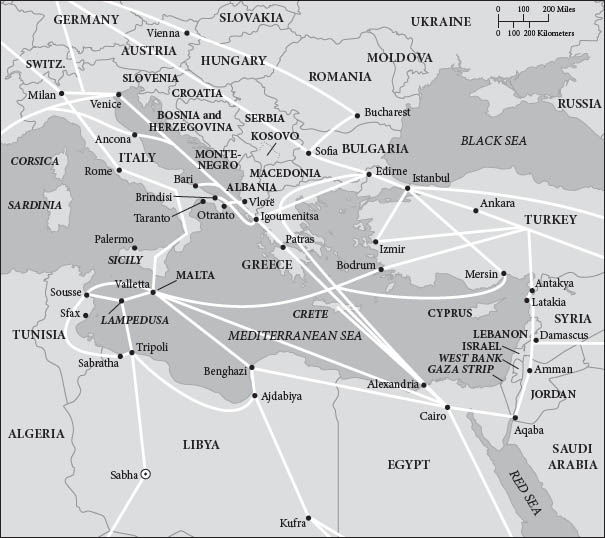

Map 1. Mixed Migration Routes. Adapted from Dialogue on Mediterranean Transit Migration 2014 i-Map (interactive map) on Mixed Migration Routes

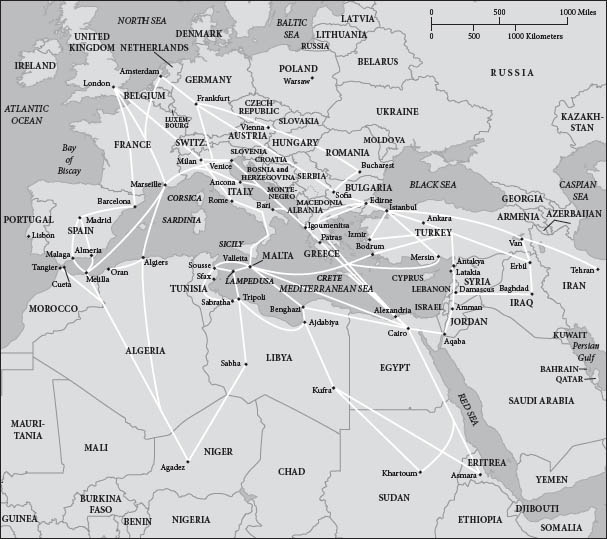

Map 2. Central and Eastern Mediterranean Mixed Migration Routes. Adapted from Dialogue on Mediterranean Transit Migration 2014 i-Map (interactive map) on Mixed Migration Routes

PART I

JOURNEYS

Introduction

On the Threshold of Liberty

The current amazement that the things we are

experiencing are still possible... is not philosophical.

This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge

unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which

gives rise to it is untenable.

Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History in Illuminations

Safe Ports

The cannon is surrounded by a variety of intricate fences. It aims at the bare torso, or perhaps at the bluish horizon beyond the steel bars, the wide-open window, and the raging flames. Agents, rescuers, and hesitant bystanders might be peeking through the airy curtains. Observers are haunted by preemptive angst.

Ren Magrittes surrealist painting On the Threshold of Liberty (1929) uncannily foreshadows recurrent anxieties over security, rights, and democracy. Its eerie suspense resonates with the condition of maritime migrants skirting the edge of the abyss. Set in the vicinity of an Italian port, in 2014, the paintings window would be open onto a procession of gray warships. They are directed to Augusta, Pozzallo, Catania, Porto Empedocle, Trapani, Ragusa, and Palermo, in Sicily; to Brindisi, Taranto, Crotone, Salerno, and Naples, on the southern Italian coast. On the warships decks stand Italian navy sailors, police agents, doctors, and Red Cross staff wearing paper-thin, white-hooded overalls, gloves, and surgical masks. Agents carry their batons, and a gun strapped to their legs. People in their charge sit on the deck in orderly fashion. Most also wear masks. Some women wear a veil and sunglasses; others show sunburned faces. Small children are nursing; older ones look with curiosity toward the city lights. Several teenagers are alone. Among them, some are pioneers, buying into a better future for the families they left behind. Others have been sent to safety by their distressed parents. Still others hope to reunite with families in northern Europe, or have become orphans. A man holds a baby intent on grabbing his glasses. Others have nothing and no one. Their eyes speak of excruciating exploitation and of physical distress. Everyone is sitting with their backs turned to the white blankets, barely covering the bodies of those who could not be rescued in time. As they climb down the boarding ladder, debilitated passengers are patiently assisted by navy sailors. Some have numbers stapled on their shirt. Wheelchairs and ambulances are waiting. The police prefect and the mayor are busy on their cell phones, as they allocate new arrivals into local facilities. Catholic clergy and local volunteer residents are also busy with preparationshospitality will need to be extended.

On the outskirts of Tripoli, the smugglers Abdel, Tesfay, From this fifth-floor room, the Italian police also coordinates the deployment of several Italian navy vessels, including two submarines, and a police plane. This constitutes the bulk of what the Italian government has termed the military-humanitarian mission Mare Nostrum. Critics in Italy and the EU disparage it as a state-owned ferry line for unauthorized immigrants and as an insurance policy for traffickers. Supporters hail it as a systematic search-and-rescue endeavor with a scope unprecedented in world history.

The 2011 Arab (Spring) Uprisings have dethroned Europes emigration gatekeepers in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya (

Since its inception in mid-October 2013, following two major shipwrecks ( Crimes of Peace traces this record.

Back in the southern Italian port, volunteers are blowing soap bubbles, if only to give children a moment of distraction. The scirocco, the southeasterly Mediterranean windsirocco, shlq, xlokk, jugo, ghiblimakes your face sticky. Locals will tell you in dialect, lu sciaroccu te trase intra llossa, it gets everywhere, it corrodes baroque buildings and ones bones. Today it brings seawater droplets right onto the news cameras lens. Haze dampens my faux-Moleskine notepad.

Alis Journey

Ali is a Hazara Afghan now in his late twenties. His journey began in 1995. One of eight siblings, he left Afghanistan when he was ten, ready to face the risks of a perilous and expensive journey, rather than the certainty of coerced Taliban recruitment. One leaves, he explains, not only because one suffers, but because of seeing others suffering. He worked for three years in Iran, where nobody ever asks who you are. After he paid $2,500, smugglers helped him cross into Turkey, walking for ten days on difficult mountainous terrain, on the same snowy paths routinely taken by thousands of people from Tehran, Baghdad, and Kabul. Some get lost; others lose limbs to the cold. Ali worked in Turkey for two and a half years in conditions worse than in Iran, with neither identification documents nor the recognition of his refugee condition. Heavy patrolling made venturing alone across the land border with Greece impossible. Markets in Izmir and western Anatolia display a variety of life vests, targeting the hundreds of people intent on reaching Greece. Ali crossed into Greece on a speedboat, but was beaten and sent back to Turkey. In a second attempt, again the police at a Greek port caught and beat him, sending him back. Ali did make it to Greece the third time, sneaking onto a ferry by hiding in a commercial truck. One of his fellow travelers died of asphyxiation. Often, others attempting to cross this way are crushed by the freight. Like them, Ali did not fear death, but rather being discovered by the truck driver or the police. In Greece, he worked in the fields for a year and a half. After several failed attempts, in the port of Patras he hid himself under the air spoiler of a truck without the driver noticing. He made it by ferry to an Italian port, which he later understood was Bari, on the southeastern coast. When the carabinieri (army police force) found him, it was impossible to communicate. Though he could speak English, no agent was able or willing to listen to the story of a journey that took eight years.

Next page