ROBERT C. VIPOND

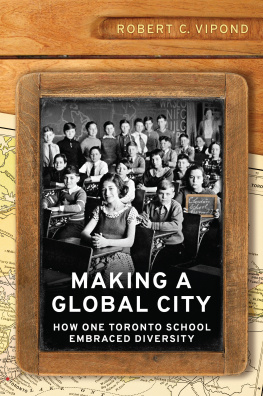

Making a global city : how one Toronto school embraced diversity / Robert Vipond.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Clinton Street Public School (Toronto, Ont.) History 20th century. 2. Public schools Ontario Toronto History 20th century. 3. Immigrant students Ontario Toronto History 20th century. 4. Multiculturalism Ontario Toronto History 20th century. 5. Toronto (Ont.) Ethnic relations History 20th century. I. Title. II. Series: Munk series on global affairs

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario.

Foreword

Why would we publish an ethnographic and political history of one inner city Toronto school in a book series on global affairs? One hint is found in the subtitle to Rob Viponds lively history of Clinton School: Making a Global City. The history of this one school helps tell the wider story of how a bastion of Anglo culture, once known as Toronto the Good (read monolithic and bland and buttoned up), became one of the most vital and diverse urban centres on earth.

But the story is even more global than the civic history would suggest. In 2016, the year that saw the rise of Trumpism, the shock of Brexit, a Hungarian referendum that ratified a refusal of an authoritarian government to take any refugees on a continent overflowing with need, this fresh story of Clinton School provides a much-needed counterpoint. It is the story of bottom-up mutual accommodation, of shifting demographics that prompt constant evolution in how a community is built and maintained, of a construction of citizenship that is both inclusive and bounded.

Professor Vipond traces remarkable Canadian immigration shifts over the course of the twentieth century that produce three distinct periods in the life of Clinton School, what he calls Jewish Clinton, European Clinton, and Global Clinton. Somehow, in each period, students who were new Canadians were made to feel that they were somebodies. When the Ontario government created regulations that sought to reaffirm a dominant Protestant culture in the 1950s, the local school community resisted and found ways to ensure that Jewish students and their families felt welcome. In the early 1960s, when children of Italian immigrants came to dominate the school numerically, communications from the school and from its parent committee were routinely sent out not only in English but in Italian (and later in other languages as well). In the 1980s, when Global Clinton emerged, the schools parent committee struggled to balance a commitment to ensure that new immigrants learned English quickly while supporting their desire to maintain their original language and culture.

The twentieth-century history of Clinton School reveals a complex, daily negotiation of what came to be called multiculturalism. Viponds story is not a simple progressive narrative, for it frankly acknowledges failures and conflict. Not all the former students interviewed had fond memories; many told stories of exclusion and bullying. Teachers sometimes remembered stronger academic commitment than the students could recount. Yet, despite the imperfections, Clinton School managed in successive generations to create forms of respect that allowed new Canadians to feel part of a receiving culture without sacrificing personal and community histories. As Vipond concludes: Finding the right balance at Clinton between acculturation and adaptation was all part of the daily routine. Every day was a practice in the construction of civic identity.

A single school in a single city can tell us much about some of the biggest issues of our own era. How can new waves of immigrants find a place in their new countries? Is a nation made up only of those who share a common history and culture? Can shared identity be built through education? What does it mean to be a citizen? In this first monograph in our Munk Series on Global Affairs with the University of Toronto Press, Vipond demonstrates vividly that the history of public education can provide helpful ways to ponder these fundamental questions. Little Clinton School in the heart of Toronto has global significance.

Prof. Stephen J. Toope

Director, Munk School of Global Affairs

Acknowledgments

This is a book I had no intention of writing. It is not the culmination of a career-long scholarly interest in the history of public education. It does not draw on a deep reservoir of research money generated by national granting agencies. And it does not fit squarely into a well-established genre of writing in my home discipline, political science. It owes its existence, rather, to a more or less chance conversation that I had, in the spring of 2012, with Wendy Hughes, principal of Clinton Street Public School in Toronto. Wendy intercepted me one morning as I was leaving the school after dropping my daughter off at her Grade 5 classroom. Are you interested in history? she asked. There was, of course, only one possible answer to that question, and before I knew it I had volunteered to be part of the committee charged with organizing the program for the schools 125th anniversary in 2013. I want to thank her for getting me hooked and for keeping me hooked.

I soon discovered that the school held a complete set of registration cards that provided demographic information about every child who had attended the school between 1920 and 1990, a well-organized archive that had been assembled at the time of the schools centenary in 1988, and loads of graduates of all ages eager to share their school and childhood memories rich resources all. I have spent most of my scholarly career reading and writing about political speeches, constitutional cases, and the like, so this project and these materials deposited me in a sort of scholarly terra incognita. I would probably still be there were it not for the generosity of friends and colleagues who know their way around. It gives me great pleasure, at long last, to be at the stage where I can thank those who have helped turn an idea into a research project, and a research project into a book.

In 201213, a half-dozen undergraduate students in political science at the University of Toronto signed up for a year-long seminar on the history of Clinton Street School. We spent the first term reading about some of the themes that animate this book the history of education, theories of citizenship, and the politics of multiculturalism among them. In the second term, the students produced major research papers based on archival research and interviews with former students and school trustees. The work they did was superb. More importantly, their work confirmed that there really was a book waiting to be written about Clinton School. To those students Jordan Kamenetsky, Scott Kilian-Clark, Taryn McKenzie-Mohr, Alissa Saieva, Nicole Stoffman, and Abby Vaidyanathan I am deeply grateful.

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.