CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

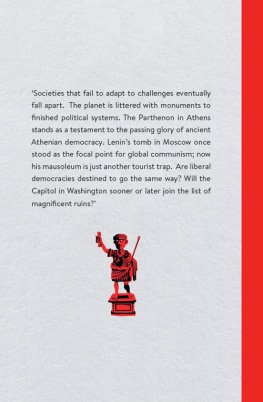

If everyone could have everything they wanted whenever they wanted, there would be no such thing as politics. Whatever the precise meaning of the complex activity known as politics might be and, as this book illustrates, it has been understood in many different ways it is clear that human experience never provides us with everything we want. Instead, we have to compete, struggle, compromise, and sometimes fight for things. In so doing, we develop a language to explain and justify our claims and to challenge, contradict, or answer the claims of others. This might be a language of interests, whether of individuals or groups, or it might be a language of values, such as rights and liberties or fair shares and justice. But central to the activity of politics, from its very beginnings, is the development of political ideas and concepts. These ideas help us to make our claims and to defend our interests.

But this picture of politics and the place of political ideas is not the whole story. It suggests that politics can be reduced to the question of who gets what, where, when, and how. Political life is undoubtedly in part a necessary response to the challenges of everyday life and the recognition that collective action is often better than individual action. But another tradition of political thinking is associated with the ancient Greek thinker Aristotle, who said that politics was not merely about the struggle to meet material needs in conditions of scarcity. Once complex societies emerge, different questions arise. Who should rule? What powers should political rulers have, and how do the claims to legitimacy of political rulers compare to other sources of authority, such as that of the family, or the claims of religious authority?

"Political society exists for the sake of noble actions, and not of mere companionship."

Aristotle

Aristotle said that it is natural for man to live politically, and this is not simply the observation that man is better off in a complex society than abandoned and isolated. It is also the claim that there is something fittingly human about having views on how matters of public concern should be decided. Politics is a noble activity in which men decide the rules they will live by and the goals they will collectively pursue.

Political moralism

Aristotle did not think that all human beings should be allowed to engage in political activity: in his system, women, slaves, and foreigners were explicitly excluded from the right to rule themselves and others. Nevertheless, his basic idea that politics is a unique collective activity that is directed at certain common goals and ends still resonates today. But which ends? Many thinkers and political figures since the ancient world have developed different ideas about the goals that politics can or should achieve. This approach is known as political moralism.

"For forms of Government let fools contest. Whateer is best administered is best."

Alexander Pope

For moralists, political life is a branch of ethics or moral philosophy so it is unsurprising that there are many philosophers in the group of moralistic political thinkers. Political moralists argue that politics should be directed towards achieving substantial goals, or that political arrangements should be organized to protect certain things. Among these things are political values such as justice, equality, liberty, happiness, fraternity, or national self-determination. At its most radical, moralism produces descriptions of ideal political societies known as Utopias, named after English statesman and philosopher Thomas Mores book Utopia, published in 1516, which imagined an ideal nation. Utopian political thinking dates back to the ancient Greek philosopher Platos book the Republic, but it is still used by modern thinkers such as Robert Nozick to explore ideas. Some theorists consider Utopian political thinking to be a dangerous undertaking, as it has led in the past to justifications of totalitarian violence. However, at its best, Utopian thinking is part of a process of striving towards a better society, and many of the thinkers discussed in this book use it to suggest values to be pursued or protected.

Political realism

Another major tradition of political thinking rejects the idea that politics exists to deliver a moral or ethical value such as happiness or freedom. Instead, they argue that politics is about power. Power is the means by which ends are achieved, enemies are defeated, and compromises sustained. Without the ability to acquire and exercise power, values however noble they may be are useless.

The group of thinkers who focus on power as opposed to morality are described as realists. Realists focus their attention on power, conflict, and war, and are often cynical about human motivations. Perhaps the two greatest theorists of power were Italian Niccol Machiavelli and Englishman Thomas Hobbes, both of whom lived through periods of civil war and disorder, in the 16th and 17th centuries respectively. Machiavellis view of human nature emphasizes that men are ungrateful liars and neither noble nor virtuous. He warns of the dangers of political motives that go beyond concerns with the exercise of power. For Hobbes, the lawless state of nature is one of a war of all men against each other. Through a social contract with his subjects, a sovereign exercises absolute power to save society from this brutish state. But the concern with power is not unique to early modern Europe. Much 20th-century political thought is concerned with the sources and exercise of power.

Wise counsel

Realism and moralism are grand political visions that try to make sense of the whole of political experience and its relationship with other features of the human condition. Yet not all political thinkers have taken such a wide perspective on events. Alongside the political philosophers, there is an equally ancient tradition that is pragmatic and concerned merely with delivering the best possible outcomes. The problems of war and conflict may never be eradicated, and arguments about the relationship between political values such as freedom and equality may also never be resolved, but perhaps we can make progress in constitutional design and policy making, or in ensuring that government officials are as able as possible. Some of the earliest thinking about politics, such as that of Chinese philosopher Confucius, is associated with the skills and virtues of the wise counsellor.

Rise of ideology

One further type of political thinking is often described as ideological. An important strand of ideological thinking emphasizes the ways in which ideas are peculiar to different historical periods. The origins of ideological thinking can be found in the historical philosophies of German philosophers Georg Hegel and Karl Marx. They explain how the ideas of each political epoch differ because the institutions and practices of the societies differ, and the significance of ideas changes across history.

"The philosophers have only interpreted the world the point is to change it."

Karl Marx

Plato and Aristotle thought of democracy as a dangerous and corrupt system, whereas most people in the modern world see it as the best form of government. Contemporary authoritarian regimes are encouraged to democratize. Similarly, slavery was once thought of as a natural condition that excluded many from any kind of rights, and until the 20th century, most women were not considered citizens.