POLITICS

ALSO BY DAVID RUNCIMAN

Pluralism and the Personality of the State

The Politics of Good Intentions

Political Hypocrisy

Representation

The Confidence Trap

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC 1 R 0 JH

www.profilebooks.com

Text copyright David Runciman, 2014

Original illustrations Cognitive Media Ltd, 2014

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by Jade Design

www.jadedesign.co.uk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 257 4

eISBN 978 1 78283 056 6

Enhanced eBook ISBN 978 1 78283 135 8

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

POLITICS

Politics matters.

If you live in Syria today, you are stuck in a kind of hell: life is frightening, violent, unpredictable, impoverished and, for all too many Syrians, short. As I write, estimates for the number of Syrians killed in the civil war range from 80,000 to 200,000. (The gulf between the estimates is a sign of how bad things are: the dead have disappeared into a cloud of disinformation.) The people who have seen their quality of life displaced runs into the millions. The number who have seen their quality of life depleted because of the violence includes just about everybody in the country (unemployment in 2014 is reckoned to be about 60 per cent). No one in their right mind would choose to live in Syria right now.

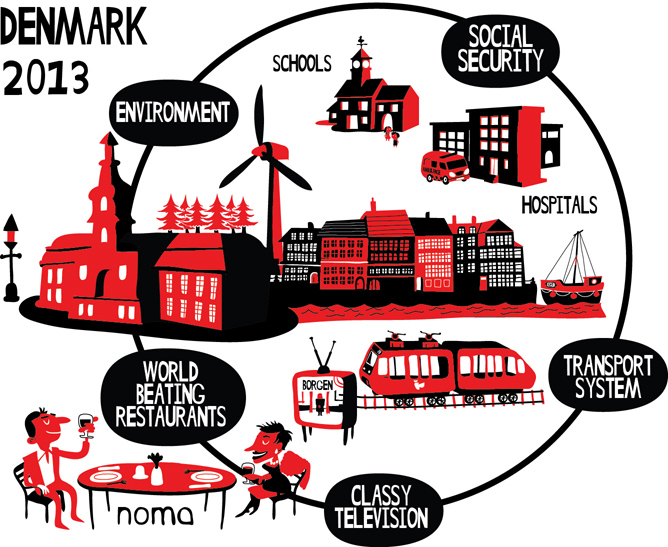

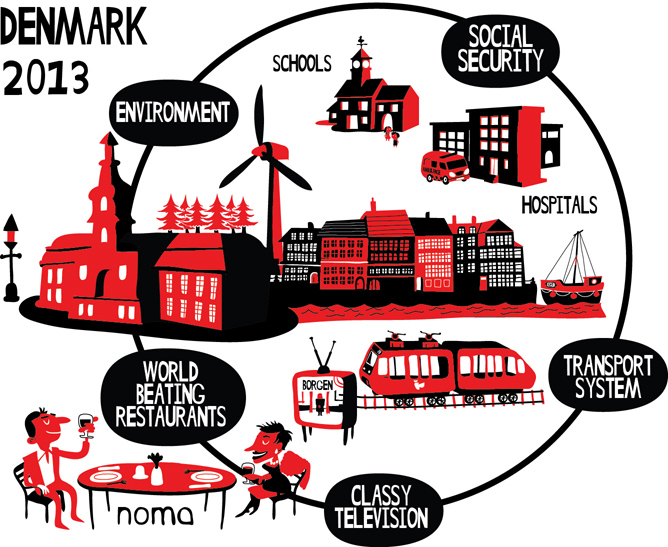

If you are lucky enough to live in Denmark, you are in what is by any historical standards a version of heaven: life is comfortable, prosperous, protected and civilised, and it lasts. The world envies Denmark its fantastic restaurants, its classy television programmes, its elegant design culture, its generous social security provisions, its environmentally friendly lifestyles. Denmark comes at or near the top of international comparisons that measure quality of life and the contentment of citizens. Danes regularly report that they are happier than anyone else. Perhaps not everyone would choose to live in Denmark: the downside, like many versions of heaven, is that it might be a little boring. But if you had no prior attachments, youd pick Denmark over Syria any day.

The difference isnt that Danes are better people than Syrians. They arent inherently nicer or smarter: people are pretty much people the world over. Nor have Danes been blessed with greater natural advantages. If anything, its the reverse: Syria is part of the fertile crescent that was once the birthplace of human civilisation; Denmark is a bleak northern outpost with few natural resources of its own. Denmark is full of nice things, but not many of them grow out of the ground. (The restaurants that have made Denmarks gastronomic reputation specialise in local produce, but they transform it with the aid of modern technology; no one would pay those prices for what the Danish soil produces on its own.)

The difference between Denmark and Syria is politics. Politics has helped make Denmark what it is. And politics has helped make Syria what it is.

To say that politics makes the difference is not to say that politics is responsible for everything good that happens in one place and everything bad that happens somewhere else. Danes arent happy because their politics make them happy: politicians seem to annoy and aggrieve the Danes just as much as they do people everywhere. Danish politicians can take some of the credit for their social security or transport systems, but they can hardly claim to be the ones who made the restaurants world-beaters or the design so desirable. Likewise, Syrias current politicians are to blame for plenty of the misery stalking their country, but they didnt invent the religious and ethnic divisions that are behind so much of the violence. The civil war has pitted Sunni against Shia; it is being fuelled by deep differences of culture and history; it was triggered by the chance effects of recession and drought. Politics doesnt create all human passions or hatreds. Nor is politics responsible for every natural disaster or economic set-back that takes place. But it either amplifies them or it moderates them. Thats the difference it makes.

Denmark today looks like a country that enjoys political stability because its people have nothing serious to fight about. Danes might be antsy about immigration, like many Europeans. But, compared with Syria, there exist none of the ethnic or cultural fissures that would provoke a civil war. As well as being peaceful and prosperous, Denmark is also a broadly secular society: religion doesnt overshadow public life, even though it does occasionally intrude. But Denmark wasnt always like this. Five hundred years ago it was more like Syria: a fragile, tempestuous, hard-scrabble place, shot through with religious conflict and violent disagreements. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when Denmark, like the rest of Europe, was regularly tearing itself apart, you would have been hard pressed to know whether it was better to live there or in Syria. Life was cheap everywhere. If anything, Denmark was the really dangerous place to be, because of the endless spill-over of conflict with its Scandinavian neighbours. For most of its history Denmark stood at the crossroads for war in Europe. Syrias borders today are an arbitrary construct, imposed on the country by victorious rival powers. But so too are Denmarks.

Yet, despite this, Denmark has made the transition from war to peace, and from a subsistence economy to a wealthy one. It did so by arriving at the social and political institutions that enabled its people to co-exist peacefully with each other and with their neighbours. How this happened is not easy to explain. The puzzle is that good politics is both a symptom and a cause of the transition. Politics works in Denmark because it has made Danes more tolerant. But it also works because Danes have learned a tolerance for politics. These are the two sides to any successful political arrangement. There is the politics that is produced by stable institutions: all the arguments and disagreements that somehow stop short of war. And there is the politics that produces stable institutions: all the arguments and agreements that somehow bring war to a stop. Politics cannot be reduced to any particular set of institutions. It precedes them, and it emerges from them.

What these two sides of political life have in common is that they both combine choice with constraint. Politics is about the collective choices that bind groups of people to live in a particular way. It is also about the collective binds that give people a real choice in how they live. Without real choice there is no politics. If it were the case that successful political institutions were the automatic product of particular historical circumstances give me the right climate, culture, economy, religion, demographics, and Ill give you democracy then life would be a lot simpler. But its not that simple. Political institutions are still shaped by human choices, and human beings always retain the capacity to screw them up. Equally, if it were the case that the right political institutions did away with the need for choice give me democracy, and Ill give you peace, prosperity, fancy restaurants, a quiet life then life would also be simpler and a lot duller. But even in Denmark the successful functioning of political institutions depends on the choices people make: choices made by politicians and by voters, choices about what laws to have and about whether to obey them. Some of these choices can be agonising: even in rich, happy countries some political decisions are matters of life and death. Nothing is automatic in politics. Everything depends on the contingent interplay between choice and constraint: constraint under conditions of choice; choice under conditions of constraint.