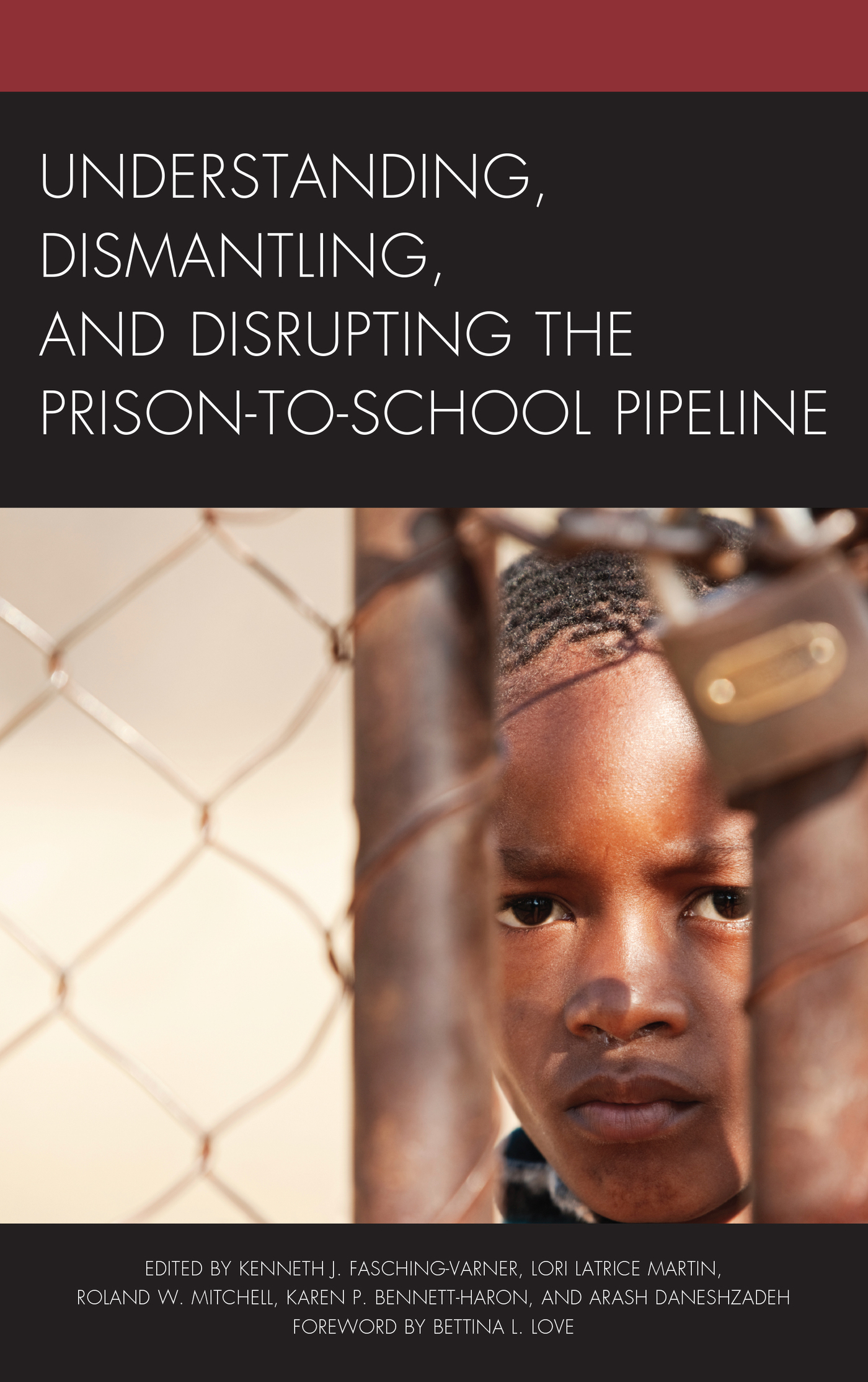

Understanding, Dismantling,

and Disrupting the

Prison-to-School Pipeline

Understanding, Dismantling,

and Disrupting the

Prison-to-School Pipeline

Edited by Kenneth J. Fasching-Varner, Lori Latrice Martin, Roland W. Mitchell, Karen P. Bennett-Haron, and Arash Daneshzadeh

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4985-3494-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-3495-6 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Foreword

Bettina L. Love

I write this foreword while sitting in an elementary school in Atlanta, GA, surrounded by the sounds of another school morning. Children laugh at the top of their lungs as they swing their book bags (or in the case of the smallest, drag them). Sneakers squeak against the hard floors as a group of students come to a screeching halt at the sight of their teachers. A teacher bends to place his hand on a childs shoulder and warmly asks him to stop running. The student apologizes with big brown eyes and a slight smile. Joyful chattering erupts all around me. Its 7:54 am, and the first bell of the day begins to ring. The hallways clear as students tuck themselves away in the classrooms.

I find a quiet spot to work. I reread a few chapters from this book and remind myself of the work of David Stovall, Bill Ayers, Monique Morris, Maisha T. Winn, Erica R. Meiners, Beth E. Richie, Michelle Fine, Anthony J. Nocella, Kimberl Crenshaw, Priya Parmar, and Michelle Alexander. These scholars with laser sharp analyses have documented the well-calculated, premeditated, heartless, spirit murdering (Love, 2013, 2016) prison-industrial complex/nexus and educational reform-industry. These two industries are deliberately entangled to profit from Americas systematic attack on Black and Brown bodies. Our youths current conditionmy current conditionrooted in White supremacy and human subjugation, never allows me to forget that I live and work in a carceral state, regardless of those childrens smiles, dreams, natural gifts, and my best intentions.

Meiners (2010) writes, The term carceral state alludes to how the logic of punishment shapes other governmental and institutional practices, even those not perceived as linked to prisons and policing (p. 122). Meiners, like many other prolific scholars writing and working to eradicate prisons altogether, have argued that slavery, anti-immigration laws, and hyper patriarchy and heteronormativity are inextricably linked to our prison nation [that] is not broken, but is functioning precisely as designed (p. 123).

As I write, here, in a public charter school where my own children sit at their desks, and where I serve as the chair of the school board, my stomach drops at the realization that my lifes work as a teacher-educator and public servant is deeply entangled in the system. This school is filled with Black children who have yet to discover that their physical lives and African spirits of self-determination, awakened by educational practices that center their culture and present lives, are up for sale through market-based approaches posing as egalitarian school reform efforts. In moments like these, I turn to the incomparable Derrick Bell, as many authors do in this volume.

Defining the foundation of racial realism, Bell (1992) writes, The Realists argued that a worldview premised upon the public and private spheres is an attractive mirage that masks the reality of economic and political power (p. 367). He states that racial realism brazenly acknowledges that Black people will never gain equality, and that our mind-set should be to avoid hopelessness and to imagine and implement racial strategies that can bring fulfillment and even triumph (p. 374). Bell reminds me that the strength to move an unmovable mountain is in the radical love and solidarity found through the work of critical resistance. I find sustenance in the intellectual work, direct action, and movement-building that produces language and strategies for everyday people to work toward collective liberation. I have no hope in the system, but all the faith in Black and Brown people and allies/co-conspirators, who work endlessly toward creating a platform that will bear fruit for the humanity and dignity of Black people.

Therefore, this volume is not just timely and important, but each author passionately and with intellectual rigor contributes to the vision of racial realism. For academics, Bells life and work should be an example of what is possible as we teach, resist, and create in peril. I lean on him when the world does not make sense, but his work reminds me that the injustice I am seeing and feeling in my everyday life has been ordered up like a lunch special at my favorite restaurant. The prison-industrial complex/nexus and educational reform-industry are predictable monsters. They feast on greed, and the authors in this book understand their appetites.

And so, it is with a heavy heart that I conclude this foreword, as I realize that many of the faces passing me by in the hallways of this very school will be stolen by Americas massive tentacles of racial inequity and racial injustice. I write not to speak the hyperbolic language of an educational cynic, but to speak the Truth. In reading this book, if confronting these brazen words, and those of the authors that follow, brings discomfort, imagine doing so on a daily basis, since you drew your first breath, and know what it is to live as a child of color. As such, the authors in this volume center disrupting and dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline by critically examining the political economy of our social institutions in a neo-liberal world. This book therefore stands as not only as reinforcement that we, as a community, have a lot of work to do, but as another piece of valuable armor for our fight.

Bettina L. Love

Atlanta, GA

Chapter 1

Free-Market Super Predators and the Neo-liberal Engineering of Crisis

Kenneth J. Fasching-Varner, Lori L. Martin, Roland W. Mitchell, Karen P. Bennett-Haron,

and Arash Daneshzadeh

Examining Twenty-First-Century Educational and Penal Realism

We edit this book, and write this first chapter, with heavy hearts. We expect that readers may find themselves feeling angry, frustrated, and sad when thinking through realities of both the educational reform and the prison industrial complexes. We are motivated, as scholars, thinkers, and humans, to approach this work with the belief that continued discourse and action are needed to address the so-called school-to-prison pipeline, or what we call death by education. To be certain, much attention has been paid to the school-to-prison pipeline (Archer, 2009; Christle, Jolivette, and Nelson, 2005; Cole and Heilig, 2011; Cooc, Currie-Rubin, and Kuttner, 2012; Darensbourg, Perez, and Blake, 2010; Feierman, Levick, and Mody, 2009; Fowler, 2011; Kim, Losen, and Hewitt, 2011; Skiba et al., 2003; Smith, 2009; Tuzzolo and Hewitt, 2006; Wald and Losen, 2003; Winn, 2011; Winn and Behizadeh, 2011). Several of the editors and authors of this volume contributed to a special issue of

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.