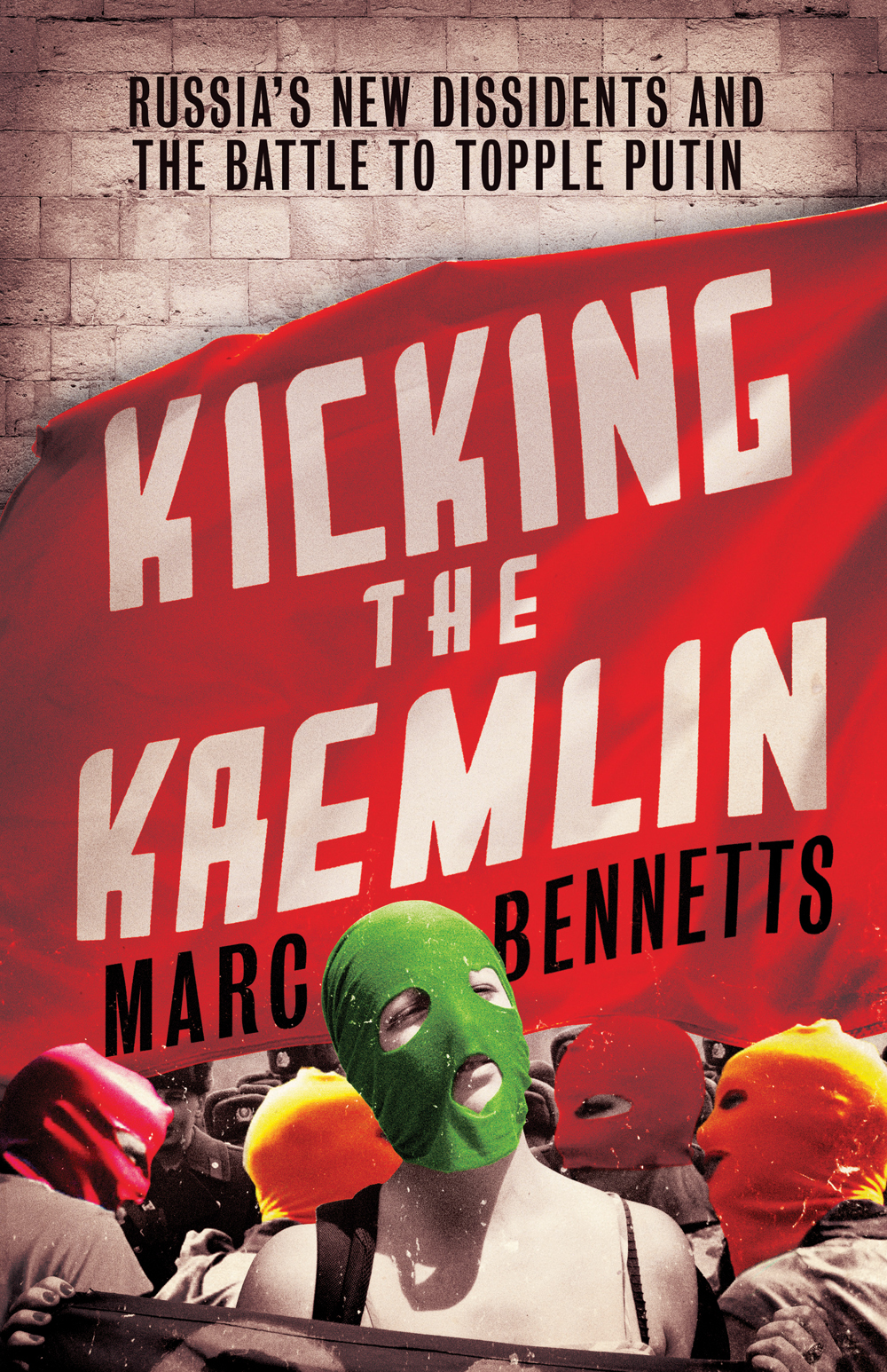

About the Author

Marc Bennetts is a British journalist based in Moscow, where he has lived for the past fifteen years. He has reported from Russia, Iran, and North Korea for the Guardian , The Times , the Observer and the New York Times , among other publications. He spent eighteen months as a reporter for Russias RIA Novosti news agency. His first book, Football Dynamo , examined Russian culture thought the countrys national sport.

A Oneworld paperback original

First published in North America, Great Britain & Australia

by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright 2014 by Marc Bennetts

The moral right of Marc Bennetts to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-348-6

ISBN 978-1-78074-349-3 (eBook)

Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Contents

List of Main Characters

The Kremlin and Its Allies

Vladimir Putin Long-time ruler of Russia, ex-KGB officer

Dmitry Medvedev Putins political protg, Russias chief blogger

Vladislav Surkov Putins grey cardinal, fan of gangsta rap

Patriarch Kirill Head of the Orthodox Church, connoisseur of luxury watches

Alexander Bastrykin Russias top investigator, opposition persecutor

The Anti-Putin Movement

Alexei Navalny Protest figurehead, Russias alternative chief blogger

Sergei Udaltsov Leftist leader, fan of really heavy underground rock

Pussy Riot Anti-Putin punk group, keen on multi-coloured balaclavas

Eduard Limonov The granddaddy of Russian radical politics

Yevgenia Chirikova Eco-activist who failed to notice the collapse of the Soviet Union

God save us from seeing a Russian revolt, meaningless and merciless!

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN

The Captains Daughter (1836)

This book is dedicated to my wife, Tanya Nevinskaya, with much love.Thank you for everything but especially for Masha!

Prologue

One Day in December

Rossiya bez Putina! came the chant. Then again, louder now, as if the tens of thousands of protesters had convinced themselves the first time around that such a thing might actually be attainable. Russia without Putin! Russia without Putin!

The words floated high into the Russian capitals frigid winter skies. The slogan would, a speaker promised as demonstrators stamped their feet to keep warm, be audible in the nearby Kremlin. Especially if the protesters turned towards its elaborate towers, still topped by Soviet-era ruby-red stars, and shouted the rallying cry once more.

Up until that exact moment, the possibility of a Russia without Vladimir Putin in charge had appeared about as probable as a Moscow winter without snow. Or, perhaps, a Russia without the engrained, high-level corruption that had seen the country slide to the very lower reaches of Transparency Internationals global corruption index, sharing 143rd place out of 182 nations with Nigeria.

But, on 10 December 2011, at Moscows Bolotnaya Square, less than a week after what had looked like a blatant case of mass vote-rigging to secure Putins United Russia party an unlikely parliamentary majority, nothing was unthinkable anymore. Moscows richest and most educated residents the so-called creative class were suddenly out on the streets in an unprecedented show of discontent. Even rank-and-file riot police looked taken aback at the size of the crowd. I spotted a group of officers taking snapshots of protesters, including a bride still in her white wedding dress, on mobile phones. (This could, of course, quite easily have been for surveillance purposes.)

To fight for your rights is easy and pleasant. There is nothing to be afraid of, said Alexei Navalny, the oppositions de facto leader, in a message passed out of a Moscow detention facility. Every one of us has the most powerful and only weapon we need a sense of our own worthiness.

Could Putin hear them? I wondered. Could he hear the disparate gathering of liberals, nationalists and leftists? The humiliated and the insulted? And, if he could, what did he feel? Fear? Shock? Or, perhaps, scorn? While large-scale dissent was a new thing for modern Russia, Putin could still boast of approval ratings that were the envy of any Western leader. He also possessed an incomparable control over national television channels, the main source of news for the vast majority of Russians.

I looked around the square at the families, the pensioners, the young men and women flush with the excitement of participation in a genuinely historic moment. I never thought Id see this, a veteran activist told me, the words pouring from her. In the past, a few hundred people turned up to protest rallies, but just look at how many there are here now. A lot of people have come to a demonstration for the first time and not the last.

*

The mass anti-Putin protests that began in Moscow that afternoon confounded analysts and inspired Kremlin critics, both of whom had believed that the ex-KGB officers long stranglehold over political life meant such a thing was all but impossible. As crowds wearing the white ribbons that quickly became the symbol of the protest movement filled the streets of the Russian capital, Putins foes could have been forgiven for believing that their arch-nemesiss days were numbered. The Kremlin seemed initially uncertain how to respond to the mass protests, alternately threatening and making half-hearted proposals on political reform. It appeared back then to many people that victory was just around the corner, recalled Sergei Udaltsov, the fiery, shaven-headed leftist who symbolically tore up a Putin portrait to ecstatic applause at a February 2012 Moscow rally.

It would not be quite so easy to get rid of the man himself. Do we love Russia? Putin yelled at a rare presidential election campaign rally in south Moscow in the spring of 2012, jabbing his finger into the driving sleet. Of course we do, he continued, after the cries of da had faded away. And there are tens of millions of people like us all across Russia.

The battle for Russia goes on! Putin told the crowd, many of them bussed in en masse from the countrys conservative heartland, as his speech came to an end, his hand reaching up then swiftly down as if to snatch victory from the chill Moscow air. And we will triumph!

Inevitably, within weeks of Putins controversial return to the Kremlin in May 2012, the long-expected clampdown began. They ruined my big day, Putin was widely reported to have said of the protesters who had marred his inauguration for a third presidential term. Now Im going to ruin their lives.