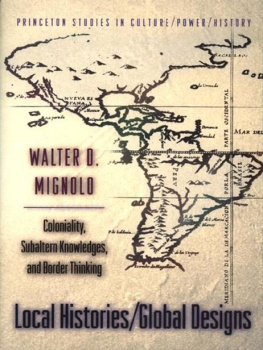

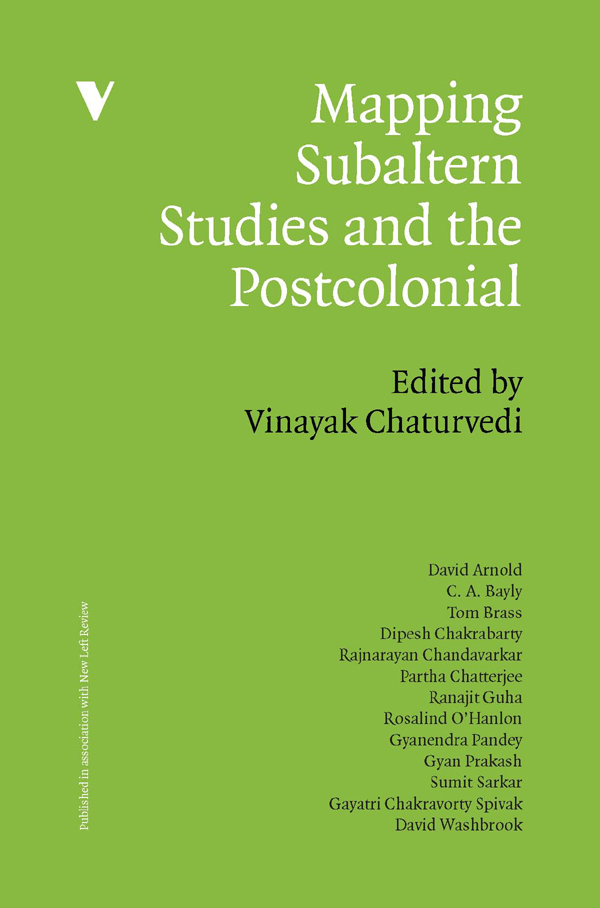

C. A. Bayly

This book maps the terrain of the Subaltern Studies project of writings on South Asian history and society. Subaltern Studies was initially conceived as a three-volume series to revise the elitism of colonialists and bourgeois-nationalists in the historiography of Indian nationalism. However, as the Subaltern Studies project became increasingly influential, its relationship to the heterodox Gramscian Marxism which had informed its founding theoretical charter became increasingly distant. This collection of essays traces the trajectory of Subaltern Studies from the Marxism of its inception, to its current post-Marxist contours, and it critically tracks the history of this transformation.

At the end of the 1970s, Ranajit Guha the founding editor of Subaltern Studies and a group of young historians based in Britain embarked on a series of discussions about the contemporary state of South Asian historiography. This was a theoretically self-conscious break from the economic determinism of orthodox Marxist scholarship, and a promise to write histories from below where subaltern classes were the subjects in the making of their own history.

There are three important factors to consider in examining the intellectual origins of Subaltern Studies whose interplay is reflective of the dialectic between Western Marxism and Indian political culture. First is the intellectual influence of Susobhan Sarkar, the eminent Bengali historian who taught Ranajit Guha as a student at Presidency College in Calcutta. was taken up by the subalternists and addressed to the colonial context. Ranajit Guha explicitly made this point in the Preface to the first volume of the series:

The aim of the present collection of essays, the first of a series, is to promote a systematic and informed discussion of subaltern themes in the field of South Asian studies, and thus help to rectify the elitist bias characteristic of much research and academic work in this particular area... The dominant groups will therefore receive in these volumes the consideration they deserve without, however, being endowed with that spurious primacy assigned to them by the long-standing tradition of elitism in South Asian studies. Indeed, it will be very much a part of our endeavour to make sure that our emphasis on the subaltern functions both as a measure of objective assessment of the role of the elite and as a critique of elitist interpretations of that role.

In addition, even if less decisive than the populist agenda of history from below, was Robert Brenners contribution to the long-standing debate on the transition from feudalism to capitalism. This point is clearly exemplified in Ranajit Guhas writings in the early 1980s, as well as in his political associations: not only was he actively involved with Maoist student organizations, but his theorization of the violent nature of subaltern ideology and consciousness reflected the political landscape of the period. For Guha, a new epistemology was required to understand the antinomian dimensions of subaltern politics. Meticulous thick descriptions of insurgency could disclose the otherwise concealed political character of peasant consciousness by reconstructing the vantage point, the spontaneous ideology of the peasant rebel.

In 1982 the project was launched with the publication of Subaltern Studies I by Oxford University Press in Delhi. The following three years witnessed the publication of Subaltern Studies II (1983), Subaltern Studies III (1984) and Subaltern Studies TV (1985), as well as Guhas seminal monograph associated with the series the previously mentioned Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983). The first four volumes of the series, under the editorship of Guha, mainly adhered to the programme of writing history from below about nineteenth- and twentieth-century India. Fragmentary episodes illustrating the autonomous politics of the people demonstrated the utility of Gramscis prescriptions: Every trace of independent initiative on the part of subaltern groups should therefore be of incalculable value for the integral historian. Consequently, this kind of history can only be dealt with monographically, and each monograph requires an immense quantity of material which is often hard to collect.

By 1986, the Subaltern Studies project was confronted with internal debates about its future development: the tradition of historical materialism had come to be seen by many as a significant, and yet limited, resource for a project which now claimed to contest Eurocentric, metropolitan and bureaucratic systems of knowledge. In addition, what had been an integral part of the project the search for an essential structure of peasant consciousness was now no longer acknowledged as valid. The repudiation of that search was, in a sense, a post-structuralist moment.

Subaltern Studies, while receiving critical acclaim in India throughout the 1980s, was largely overlooked in North America, and even in a Britain of multiple Marxisms. Subaltern Studies, as practised in volumes VIIX (199299), has assumed increasingly pronounced post-Marxist forms, as it has accommodated itself to the culturalist atmosphere of US humanities departments.

There is more than a little irony in all this. Whereas Subaltern Studies began as a critical engagement with Marxism in the early 1980s, much of the writing from the collective in the following decade, having shifted methodologically and theoretically, could best be identified with what may be called a certain spirit of Marx. It is testimony to the perennial importance of the issues made central by the original Subaltern Studies collective that the problems of agency, subject positions and hegemony constitute to the ontological resistance of all varieties of historical determinism, techno-economic or cultural.

The texts included in this volume represent a balance sheet of the Subaltern Studies project. They provide a panoramic view of the seminal writings emerging from the key theorists of Subaltern Studies between 1982 and 1999. Also included in the collection are selections from distinguished intellectuals specializing in Indian history and politics, whose writings provide a comprehensive assessment of the origins and formal shifts in the project. As a caveat, it may be important to say something about the necessary omissions from the collection. Due to the large secondary literature emerging around the project in recent years, it has been difficult to include all relevant essays which would have made this volume complete. Readers will find that there are no inclusions of essays from the first reception of the project in India, although two later essays are included; it would be otiose to reproduce essays here which comprise a central focus of a forthcoming volume on the histories of dialogue around Subaltern Studies. In making the selections, an attempt has been made not to repeat essays and discussions from the original series. There are two important reasons for such a choice: first, as the members of the collective emphasize their own autonomous voices within the project, it was pertinent to select essays which were published independently of the series and reflected theoretical shifts in the 1980s and 1990s; second, by presuming an audience which was already familiar with the original essays found in the pages of Subaltern Studies , this volume was designed to be a companion collection of texts. The essays are organized according to the intellectual trajectory of the project. Theoretical statements from the members of the Subaltern Studies collective are followed in sequence with critiques, thereby providing a historical framework for the discussions and debates centring on the project. With the exception of the first essay by Ranajit Guha from Subaltern Studies I and a new interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the initial pieces were published in academic journals and edited volumes in India, Britain and the USA. However, it should be emphasized that the essays selected for this volume do not presume a specialized knowledge of Indian history or politics, and can be read independently of the series. The aim is to provide sources for addressing the relationship of Subaltern Studies to contemporary social theory, while also contributing to the ongoing debates in the social sciences and humanities.