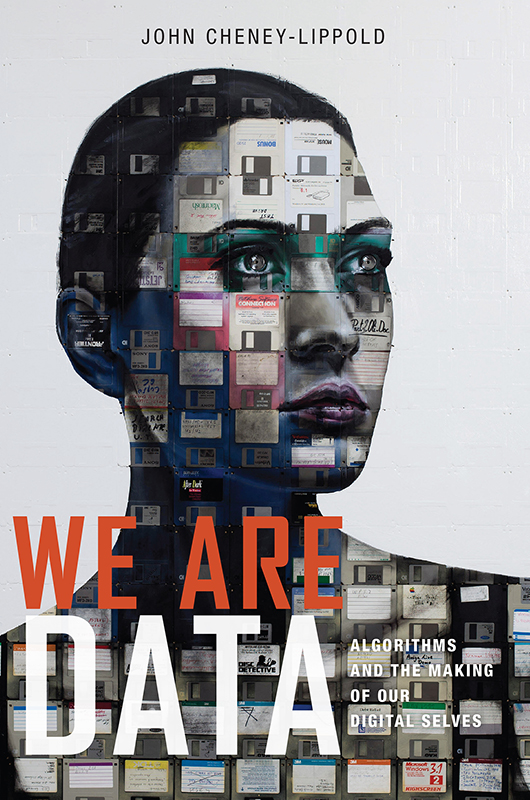

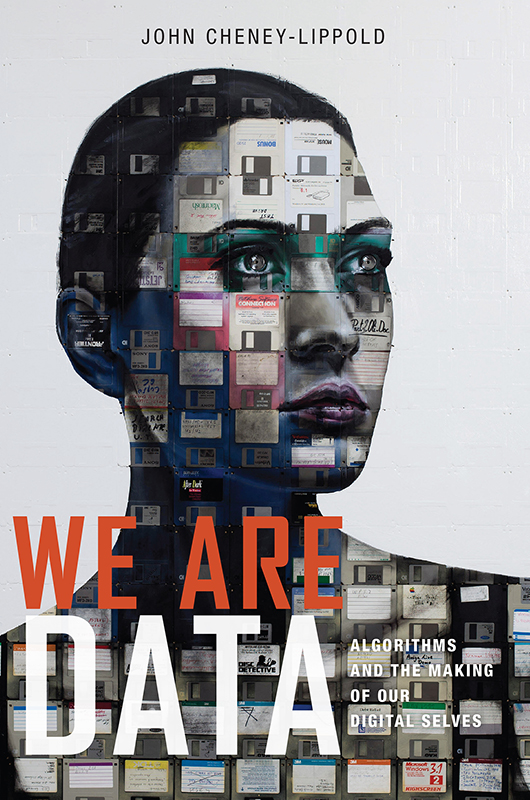

We Are Data

We Are Data

Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves

John Cheney-Lippold

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-5759-3

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To Mamana Bibi and Mark Hemmings

Contents

Are you famous?

Celebrities are our contemporary eras royalty, the icons for how life ought (or ought not) to be lived. They and their scrupulously manicured personae are stand-ins for success, beauty, desire, and opulence. Yet celebrity life can appear, at least to the plebeian outside, as a golden prison, a structurally gorgeous, superficially rewarding, but essentially intolerable clink. The idea of the right to privacy, coined back in the late nineteenth century, actually arose to address celebrity toils within this prison. Newspaper photographers were climbing onto tree branches, peering into high-society homes, and taking pictures of big-money soirees so as to give noncelebrity readers a glimpse into this beau monde. Our contemporary conception of privacy was born in response to these intrusions.

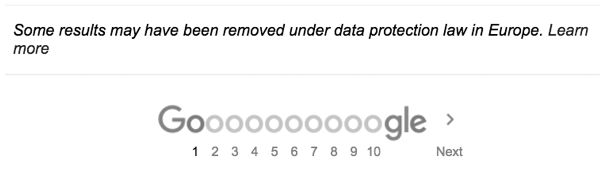

For those of us on the outside looking in, our noncelebrity identity and relation to privacy may seem much simpler. Or is it? How can one really be sure one isor is nota celebrity? Its easy enough to do a quick test to prove it. Go to google.co.uk (note: not google.com), and search for your name. Then, scroll to the bottom of the results page. Do you see the phrase Some results may have been removed under data protection law in Europe (figure P.1)? The answer to this questionwhether this caveat appears or notwill tell you how Google, or more precisely Googles algorithms, have categorized and thus defined you.

If you encounter this phrase, it is an algorithmic indication that Google doesnt consider you noteworthy enough to deserve the golden prisonyou are not a celebrity, in the sense that the public has no right to know your personal details. You are just an ordinary human being. And this unadorned humanity grants you something quite valuable: you can request what European Union courts have called the right to be forgotten.

Figure P.1. When searching for your name on Google within the European Union, the phrase Some results may have been removed under data protection law in Europe appears if you are not a Google celebrity. Source: www.google.co.uk.

In 2014, Google was forced by EU courts to allow its European users the right to be forgotten. Since May of that year, individuals can now submit a take-down request of European search results that are inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant, or excessive in relation to those purposes and in the light of the time that has elapsed.

In response, Google quietly introduced a new feature that automates part of this take-down process. In a letter to the European Unions data-protection authorities, Googles global privacy counsel, Peter Fleischer, explained that since most name queries are for famous people and such searches are very rarely affected by a removal, due to the role played by these persons in public life, we have made a pragmatic choice not to show this notice by default for known celebrities or public figures.request the removal of certain search results or a celebrity who presumably just has to lump it when it comes to privacy.

This pragmatic choice is algorithmican automatic, data-based division between celebrities or public figures and the rest of us. Yet the EU legal opinion did not define who counts as a public figure. Google gets to make it up as it goes. The exact method by which it does this is unknown, hidden behind the computational curtain. Washington Post legal blogger Stewart Baker, who first brought this algorithmic assessment to public attention, found that Google believed pop singer Rihanna to be Google famous but Robyn Rihanna Fenty (the singers legal name) not. The distinction is intriguing because it shows a gap, a separation that exists primarily at the level of knowledge. In this case, Google isnt really assessing fame. Google is creating its own, proprietary version of it.

Of course, fame, much like Google fame, has always been a creation. Film studies scholar Richard Dyer detailed this point many decades ago: who becomes a flesh-and-blood celebrity, or in his words, embodies a star image, is neither a random nor meritocratic occurrence. A star image is made out of media texts that can be grouped together as promotion, publicity, films, and commentaries/criticism.

Suitably, the site of any stars making is also a site of power. In the case of Hollywood and other mass-media industries, this power facilitates profit. But of equal importance is how these industries simultaneously produce what cultural theorist Graeme Turner calls the raw material of our identity.

But Googles celebrity is functionally different. When Google determines your fame, it is not trying to package you as a star image, nor is it producing raw material for cultural consumption. Rather, it is automatically fulfilling a legal mandate to facilitate European Union personal information take-down requests. And it is through this functional difference that Google has structurally transformed the very idea of fame itself. By developing an algorithmic metric that serves as a data-based stand-in for celebrity, Google created an entirely new index for who legally has the right to be forgotten (noncelebrities) and who doesnt (celebrities).

In short, Googles algorithmic index is an emergent way of thinking about what a celebrity is in our contemporary, data-rich communications environment. And in doing so, this emergent index fundamentally reworks our ideas around identity. In the present day of ubiquitous surveillance, who we are is not only what we think we are. Who we are is what our data is made to say about us.

Through Googles extensive database network, celebrities are a different form of star and thus produce another kind of raw material for who we are seen to be online. And in this difference is where the line between celebrities and the rest of us begins to blur. A Google celebrity may not be an actual celebrity. Rather, a Google celebrity is someone whose data is algorithmically authenticated as such. And while Google users might not grace the covers of magazines, they do produce an unprecedented amount of information about themselves, their desires, and their patterns of life. This data is a different type of raw material according to a different kind of industrywhat media scholar Joseph Turrow calls the new advertising industry and WikiLeaks described as the global mass surveillance industry.

Next page