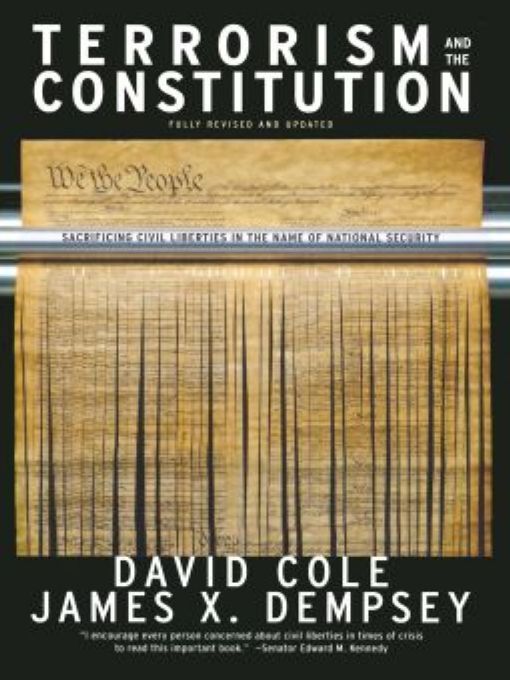

Table of Contents

Also by David Cole

Enemy Aliens:

Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms

in the War on Terror

No Equal Justice:

Race and Class in the American Criminal Justice System

To Don Edwards,

for his lifetime commitment to the First Amendment,

from his leading role in the successful campaign to abolish the

House Un-American Activities Committee to his still-unfulfilled effort

to enact a law prohibiting the FBI from undertaking investigations

infringing on the First Amendment. As longtime chairman

of the Civil and Constitutional Rights Subcommittee of the

House Judiciary Committee, Don Edwards cheerfully and

tirelessly pursued a principled and consistent oversight of the FBI.

His vision was simple and enduring: that domestic tranquillity

can be secured without sacrificing the blessings of liberty.

Preface to the Third Edition

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, marked a quantum leap in the deadliness and audacity of terror. They revealed a vulnerability that many in the United States had never before appreciated. And they sparked a fundamental debate about the tension between liberty and security in the United States, and in particular about the capability of our government to keep us secure within the confines of due process, respect for freedoms of speech and association, and a system of government powers subject to checks and balances. This third edition of Terrorism and the Constitution, like the first, addresses these questions, and provides important historical perspective on the dangers of affording the government unchecked power in an effort to attain greater security.

The first edition of this book, written in 1999, did not foresee the devastating scope of the attacks of September 11. However, in that first edition, we predicted that there would be terrorist attacks against the United States and against U.S. interests abroad. We also warned that the federal antiterrorism effort then in place was flawed and ill suited to meet the terrorist threat. Unfortunately, despite some important improvements in the counterterrorism programs of the U.S. government, we must repeat those warnings today. Major elements of the governments reaction to terrorism have been misguided not merely because they sacrifice civil liberties but also because, as is becoming clear, unchecked government power ultimately undermines security.

By their very scale, the events of September 11 have required all of us to reassess what is thinkable and unthinkable. The failure of U.S. authorities to detect the September 11 attack in advance, despite its scope and scale, mandated comprehensive reconsideration of our intelligence capabilities and powers. Yet this reexamination did not even begin until after the USA PATRIOT Act was adopted and after many other constitutionally suspect initiatives were launched. These steps were taken without asking what went wrong before September 11 and what measures would be more effective in preventing such failure in the future. The joint inquiry of the Congressional Intelligence Committees in 2003 and the 2004 report of the 9/11 Commission shed important light on the failures, chief among them turf battles, lack of skilled professionals, misplaced priorities, and an inability to analyze information. Notably, neither of the inquiries found fault with the constitutional principles of due process, accountability, or checks and balances.

To the contrary, one of the lessons of the four years since September 11, 2001, is that, even as we face new and more difficult challenges, the fundamental principles that ought to govern the response of a democratic society to terrorism remain unchanged: we should focus on perpetrators of crime and those planning violent activities, avoid indulging in guilt by association and ethnic profiling, maintain procedures designed to identify the guilty and exonerate the innocent, insist on legal limits on surveillance authority, bar political spying, apply checks and balances to government powers, and respect basic human rights. Departing from these principles, as the military and intelligence agencies have done, for example, in abusing detainees at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, is not only wrong but actually harms national security by fueling anti-American sentiment. The first edition of this book foresaw and discussed all of these issues, illustrating them with specific historical examples. These issues are all the more pressing in the wake of September 11, and the history all the more important to keep in mind. If we are to learn from our mistakes, we must not lose sight of how we have gone astray in the past.

Much has changed since September 11, however, and therefore this third edition includes a thoroughly revised text, with particularly substantial changes to Chapter 6 (addressing, among other issues, the changes in attorney general guidelines on terrorism investigations) and a new Part IV, detailing and assessing the antiterrorism measures adopted in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

The need for a revised third edition illustrates the ever-developing nature of the struggle to preserve liberty while providing security. We hope that our book offers some contribution to the ongoing debate, as this issue is likely to define the character of our nation for generations to come.

David Cole

James X. Dempsey

October 2005

Foreword to the Third Edition

The indiscriminate arrests from 1919 to 1921 of thousands of immigrants and suspected radicals, known as the Palmer Raids; the internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II; the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in the 1940s and 1950s; and the FBIs Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) in the 1960s and 1970s were all U.S. government programs that dealt harshly with individuals considered to be subversive. In all these cases, the government reacted to real and perceived security threats by sacrificing the rights and liberties of immigrants, citizens who opposed government policies, or both. Limited public opposition and overly broad government secrecy helped sustain some of those policies for decades, until enough people found the courage and clarity of purpose to mobilize sufficient opposition to bring them to an end.

Terrorism and the Constitution takes a critical look at the history of government abuses and peoples mobilization to stop themin the courts, in Congress, and in the court of public opinionoffering a compelling case for the claim that sacrificing civil liberties does not necessarily make us safer, but more often than not results in gratuitous abuse of the rights of the most vulnerable without appreciably advancing security. It is our hope that this book can serve as a tool for organizing the kind of political support for civil liberties that is critical to restoring the principles of liberty and justice that characterize this nation at its best. That work has already begun, in part with the help of this books earlier editions.

After September 11, 2001, it was impossible for those familiar with the U.S. governments history of overreaching in times of crisis not to recognize the patterns, as Arab, Muslim, and South Asian immigrants were rounded up indiscriminately, the Justice Departments surveillance powers were expanded through executive fiat, and Congress steamrolled passage of the USA PATRIOT Act in late October 2001.