1. Old dreams and new realities

Owning ones own home has been a rite of passage for generations of New Zealanders. Home ownership has long offered financial security and played a central role in our national identity. But growing numbers of New Zealanders, especially the younger generations, now find themselves excluded from the dream of home ownership and consigned to a second-rate existence as renters. After rising for nearly a century, home-ownership rates in New Zealand began falling in 1991, and have continued to fall. Home ownership is now especially difficult to achieve in Auckland but there are challenges in many parts of the country. Not owning a home in New Zealand often means being bereft of both social and financial security. There is comfort in having a tangible asset, something you can touch and feel and call your own. There is also the security of belonging to a community and observing a cultural norm of having something in common with your family, neighbours, and community. In New Zealand, owning your own home is a sign that you have truly become an independent adult.

Owning a home is in this sense a cultural expectation. And, before house prices began soaring in the 1990s, when houses were still affordable for the average earner, there was a recognised path towards home ownership. It was possible for many to climb the property ladder by starting small, accumulating wealth throughout their early careers, and upgrading over time to a larger family home. It was not easy, partly because financial markets were not developed enough to offer reasonably priced mortgages. But it was attainable. And there were many successive government policies to help people into home ownership.

Today, talk of houses and house prices dominates the media and is a hot topic at many dinner tables. It remains part of our culture. But home ownership is becoming increasingly limited to the relatively well-off. If current trends continue, we risk seeing a massive inequality in wealth develop between generations and within future generations.

In the future, it may be that only the children of home owners will be able to own homes, because few will otherwise have sufficient incomes to buy one on their own. Hereditary bequests or financial help from parents may well become the path to home ownership. Such an inheritance-based class system goes against the grain of what New Zealand is supposed to aspire to: an equitable and egalitarian society. This new reality is a cause of alarm for many young (and old) New Zealanders:

The modern generation has experienced a very tough economic adulthood. We graduated from university in the later half of the 2000s, only to arrive at a financial crisis that crippled our post-graduation dreams. Over the last seven years, weve fought tooth and nail to do well at work, live on the cheap, and ferret away a house deposit. Now, many of us (thanks to KiwiSaver) actually have that house deposit, and even the mortgage pre-approval is ready to go. Trouble is, we cant afford to buy a house in 2015. We can only afford to buy a house in 2005. So, were now 30, and unlike every generation before us, we will still be renting into our fourth decade.

Figure 1.1 Home-ownership rate over time (owner-occupied share of all defined tenures, excluding unidentified tenures)

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand censuses and New Zealand Official Yearbook.

A broken housing market also means a raw deal for renters. Renting has not traditionally been part of the Kiwi dream; it has always seemed like a second-rate option. But it doesnt have to be that way. In other countries, people can rent for very long periods of time without any sense of inferiority. They can be just as fulfilled and happy as people who own their own home. That could be the case in New Zealand as well. While home ownership should be available to everyone who wants to pursue it, for those who dont, renting should be a good option. But at the moment, it isnt. A lot of rental housing is in very poor condition, and tenants have few rights and little security.

As it stands, a broken housing market isnt working for either people on low and middle incomes who want to buy a house, or people who in a different world might be happy renting. The decline of home ownership has struck at the heart of the Kiwi dream so perhaps it is time to fashion a new one.

Home ownership is falling

Home-ownership rates have varied greatly over the last century. As illustrated in , they rose steadily from the 1930s, often with government support, especially following the Second World War. Home-ownership rates hit 70 per cent by the 1960s thanks to the support of successive governments, rising incomes and improving financial conditions. They then peaked in the early 1990s, when just over three-quarters of the adult population owned their own home (excluding those who did not define the tenure of their housing, that is, whether they rent or own). Home ownership has since been falling, and by 2013 just under two-thirds of households lived in a non-rental property. If one looks at individuals rather than households, just over half of all Kiwis now live in a rented home.

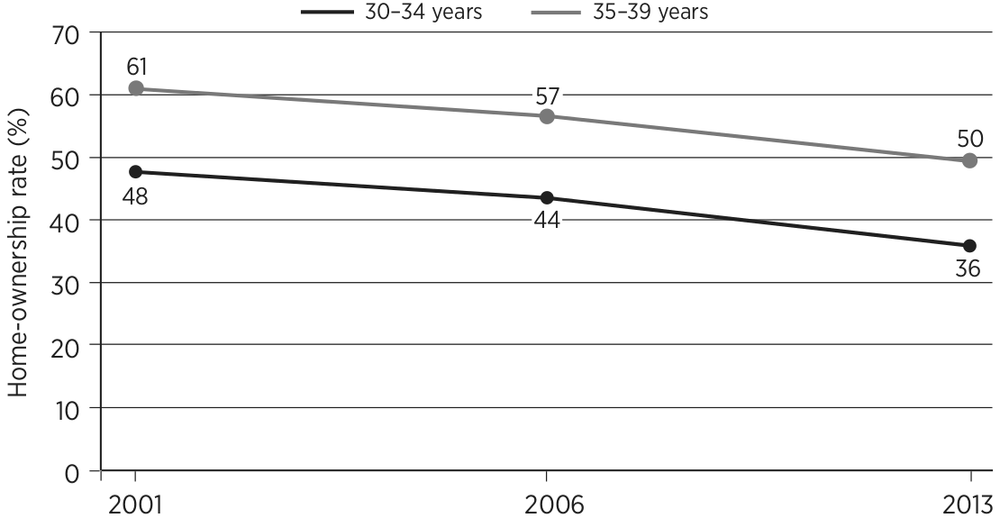

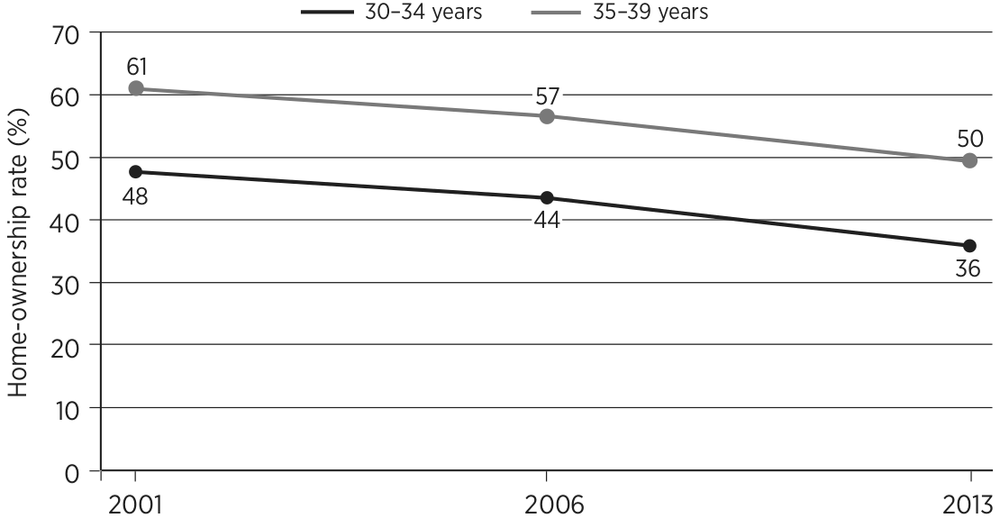

Figure 1.2 Home-ownership rate for those aged 3039

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand, 200113 Censuses.

This fall in home ownership has been most dramatic among those born after 1980. As Those who own homes in this future will mainly be older people, with younger generations remaining renters for longer or indeed for their entire life.

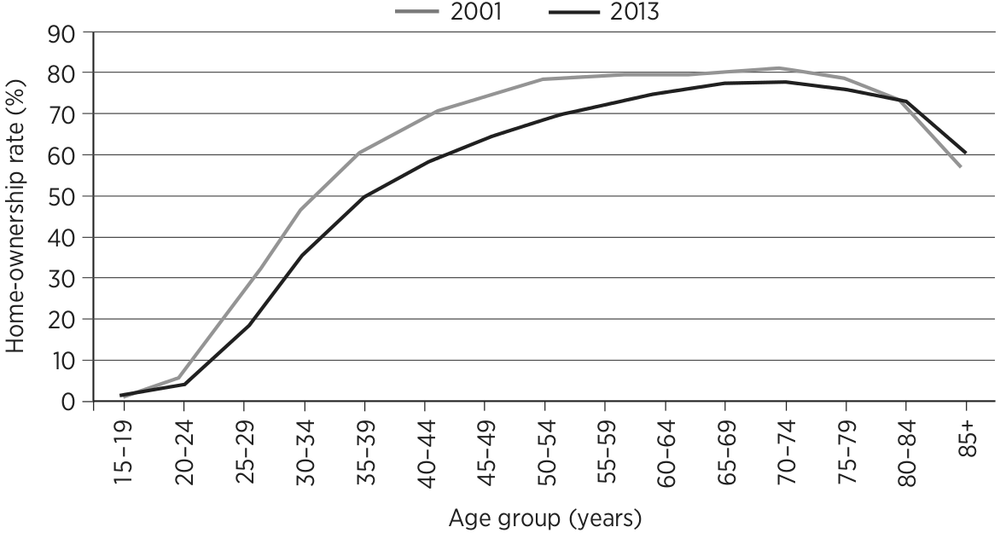

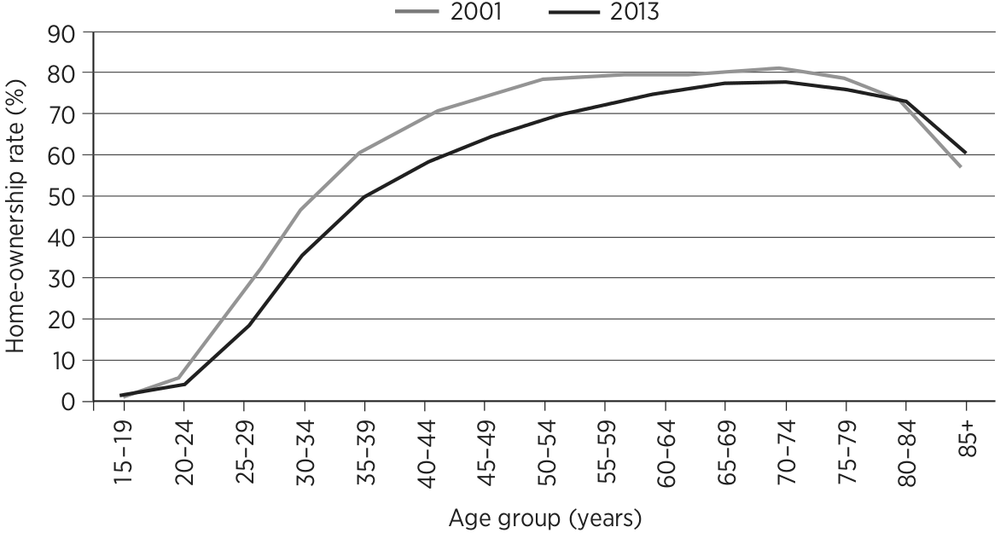

But the problems are not confined to the younger generation. Home-ownership rates do increase with age: people buy homes as they get older, as their incomes improve and as their life circumstances change. On reaching retirement, most people tend to hang on to their houses; some sell as they reach very old age (over eighty). This pattern remains in place and is visible in So the issues of housing unaffordability, renting, and rental conditions are not those of a minority group. In this sense, Generation Rent describes the experiences not only of those born after 1980 but also of many older people who have similarly given up on the hope of buying a house. And that is simply because those houses have become unaffordable. These would-be home owners, young and old, have been priced out of the market.

Figure 1.3 Home-ownership rate by age group, 2001 and 2013 Censuses

Source: Data from Statistics New Zealand, 200113 Censuses.

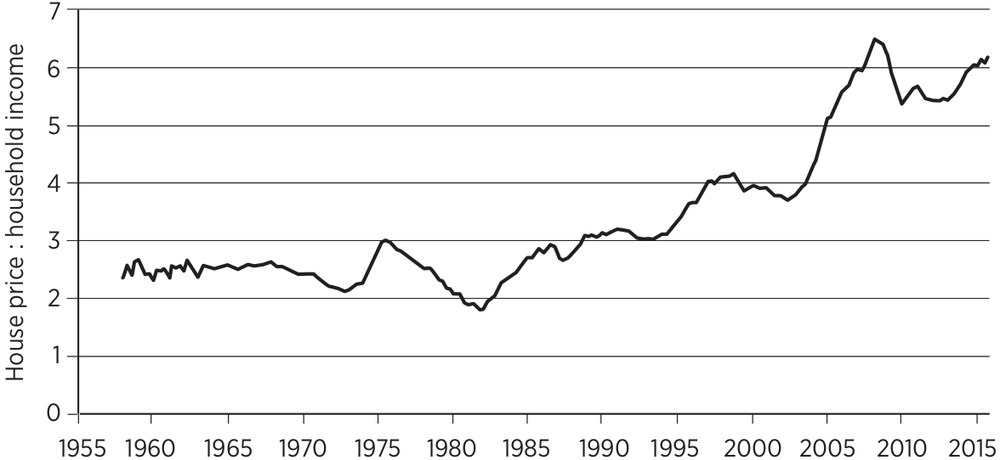

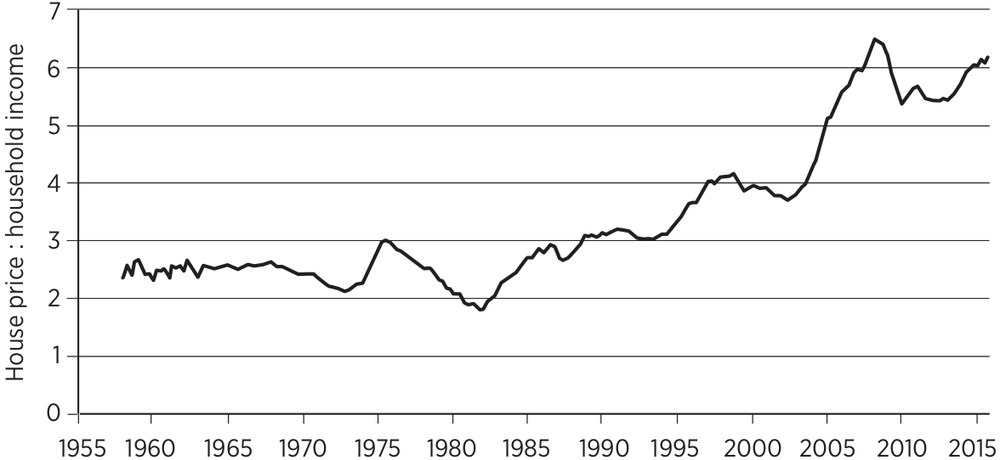

Figure 1.4 Average house price to average annual household income ratio, 19572014

Note: Average house price is expressed as years of current income. Households will not spend all their income on housing, but this measure avoids the differences in interest rates and inflation over time, which can muddy the historical comparison.

Source: Data from QVNZs Residential House Values, Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), Statistics New Zealand and NZIER.