Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

National Postal Museum: .

Office of War Information, Wikimedia Commons: .

INTRODUCTION

W HY THE P OST O FFICE M ATTERS

T HE HISTORY OF ITS POST OFFICE is nothing less than the story of America. Of the nations founding institutions, it is the least appreciated or studied, and yet for a very long time it was the U.S. governments major endeavor. Indeed, it was that government in the experience of most citizens. As radical an experiment as America itself, the post was the incubator of our uniquely lively, disputatious culture of innovative ideas and uncensored opinions. With astonishing speed, it established the United States as the worlds information and communications superpower.

After the Revolution, America needed a central nervous system to circulate news throughout the new body politic. Like mail service, knowledge of public affairs had always been limited to an elite, but George Washington, James Madison, and especially Dr. Benjamin Rush (a terrible physician but a wonderful political philosopher) were determined to provide the people of their democratic republic with both. Their novel, uniquely American post didnt just carry letters for the few. It also subsidized the delivery of newspapers to the entire population, which created an informed electorate, spurred the fledgling market economy, and bound thirteen fractious erstwhile colonies into the United States. For more than two centuries, the founders grandly envisaged postal commons has endured as one of the few American institutions, public or private, in which we, the people, are treated as equals.

The America of the Early Republic desperately needed physical as well as political and economic development. The government quickly mapped this terra incognita with post routes that connected towns centered on post offices; it also subsidized the nascent transportation industry, then dominated by the stagecoach, by paying its owners to carry the mail. By 1831, French political philosopher and mail coach passenger Alexis de Tocqueville wondered over Americas unparalleled communications system, which brought the latest national and foreign news even to the Michigan outback.

By the time of Tocquevilles visit, the founders ideal of nonpartisan politics had faded, and the post they created to unite opinionated Americans could divide them as well. President Andrew Jackson, a slaveholder, fumed when abolitionists used the network to send their unsolicited publications to Charleston, South Carolina, where irate locals committed a federal crime by burning the maila conflagration that illuminated slavery as a national rather than merely regional issue. Yet Jackson himself scandalously politicized the post with his spoils system, which allowed the party that won the White House to hire its supporters for postal jobs wrested from the defeated rivals ranksa gold mine of patronage that cemented and sustained the countrys two-party system for the next 140 years.

In the 1840s, the post faced the worst crisis in its history. Antebellum Americans, including the migrants moving from farms to cities, and increasingly to the western frontier, protested its high letter postage by turning to cheaper private competitors that contested its exclusive right to carry mail. The post responded by turning personal correspondence, historically a costly luxury, into a cheap daily staple, which both aided its recovery and transformed Americans personal lives. The combination of postage for pennies and the Railway Mail Servicea now forgotten wonder that efficiently processed mail aboard moving trainslater enabled many people to write to a friend in the morning and receive a reply that afternoon.

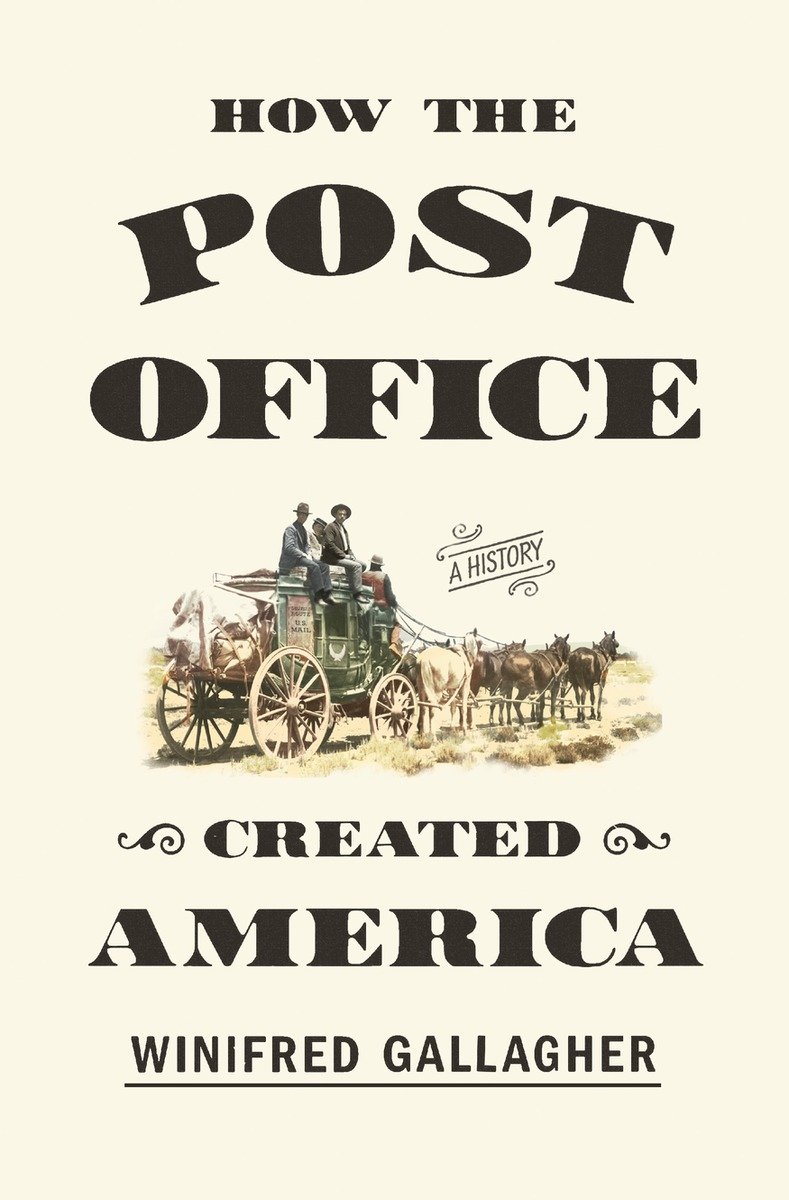

The post played a crucial role in one of the nineteenth centurys crowning achievements: turning the Atlantic-oriented United States into a Pacific nation as well. The transcontinental telegraph and railroad of the 1860s usually get the credit, but they followed in the tracks of a post that was already responding to the needs of historys greatest overland migration. (Most settlers got their mail at post offices in general stores, much like the one served by the young postmaster Abraham Lincoln on the Illinois frontier.) The post subsidized the Overland Mail Companys western stagecoaches but only paid the Pony Express to carry mail at the end of its short life, when the private service helped to keep distant California slavery-free and connected to the rest of the Union.

Like America itself, the post was transformed by the Civil War. When the Confederacy stole its entire southern network, Montgomery Blair, Lincolns brilliant postmaster general, used the savings from the discontinued operations to pay for expensive new services, including Free City Delivery, which brought mail to urban doorsteps, and the postal money order system, which initially enabled Union soldiers to send their salaries back home safely. The post had been the first, and was for a very long time the only, institution to give jobs to disenfranchised women that offered them rare entre into public life. Most had been small-town postmasters, but Blair went further, hiring women for prestigious positions as clerks even at the departments august headquarters in Washington, D.C. The post had long been prohibited from using enslaved workers, lest they learn from publications circulated in the mail that all men were created equal. After the war, the victorious Republicans underscored their politics by employing significant numbers of African Americans. As a black woman, sharpshooting, cigar-smoking Stagecoach Mary Fields, a former slave who transported the mail by wagon in the wilds of Montana, broke both barriers.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the post became a progressive champion for Americans who looked to the government to protect them from the Industrial Revolutions dark side, notably the powerful new monopolies that deprived them of affordable, competitively priced services. Their fearless if improbable spokesman was Postmaster General John Wanamaker, the Republican merchant prince. Critics accused him of running his department like his legendary namesake department store in Philadelphia, but he used his business genius on behalf of average Americans to fight for Rural Free Delivery and broaden the meaning of postal to include parcel delivery and even savings banking.