Gailey - Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands

Here you can read online Gailey - Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Tonga, year: 1987, publisher: University of Texas Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Texas Press

- Genre:

- Year:1987

- City:Tonga

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The first book to examine in detail how and why gender relations become skewed when classes and the state emerge in a society.

Gailey: author's other books

Who wrote Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Texas Press Sourcebooks in Anthropology, No. 14

Kinship to Kingship

Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands

Christine Ward Gailey

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

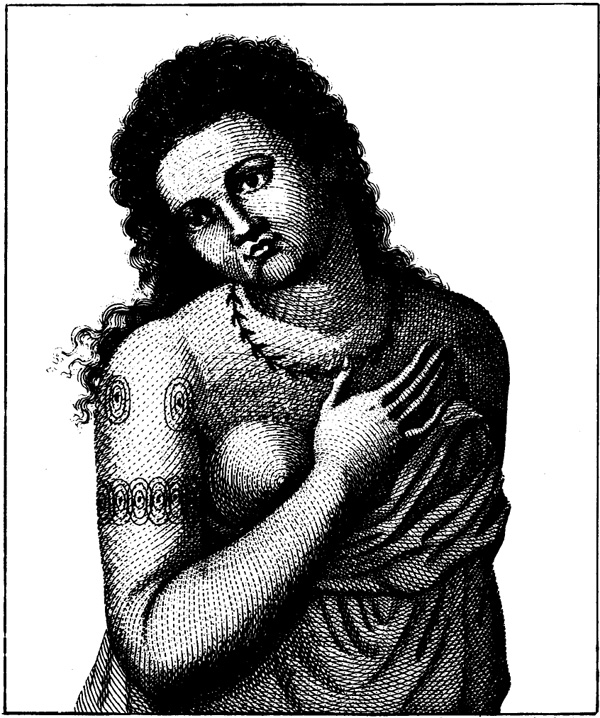

Woman of the Friendly Islands. Engraved by Springsguth. From Labilliardire 1800.

Copyright 1987 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 1987

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

Box 7819

Austin, Texas 78713-7819

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gailey, Christine Ward, 1950

Kinship to kingship.

(Texas Press sourcebooks in anthropology ; no. 14)

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. KinshipTonga. 2. Sex roleTonga. 3. AcculturationTonga. 4. TongaPolitics and government. 5. TongaSocial conditions. I. Title. II. Series.

BN671.T5G35 1987 306.83099612 87-10804

ISBN 0-292-72456-X

ISBN 0-292-72458-6 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-292-73390-9 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-73391-6 (individual e-book)

DOI 10.7560/724563

Figures

Acknowledgments

WRITING DEVELOPED out of census and tax records and retains a sense of alienated communication. We write in isolation, but cannot write critically without the love and support of others. My mother, Margaret Pearsall Gailey, transcended her ambivalence about her childless daughter and provided open arms, wonderful stories, and steady encouragement until her death. Learning about Tongan people helped me appreciate my other parents. Stanley Diamond guided my graduate work, and in subsequent years he has always been there for me in terms of theoretical discussions, political analysis, and inimitable caring. Eleanor Burke Leacock gave me a sense of anthropology as a life-long commitment to understanding and conveying the social and historical origins of exploitation, and of the obligation to apply that knowledge in practical ways to oppose class, race, and gender stratification. Both of them have helped me to avoid the trap of disciplinary and linear thinking and have led me to perceive the potential of anthropology as a critique of civil society.

A number of other friends and colleagues also have read chapters and given useful criticisms. I want to thank Laura Anker, Louise Berndt, Mona Etienne, Viana Muller, Timothy Parrish, Betty Potash, Michael Schwartz, and Irene Silverblatt for their efforts to keep me from waxing hopelessly obscure or repetitious. Tom Patterson has been especially generous and insightful in reviewing the manuscript, far beyond the call of friendship.

The College of Arts and Sciences at Northeastern University provided funding for the fall 1986 field research in Tonga. My colleagues in the Sociology and Anthropology Department, especially Debra Kaufman, Alan Klein, Elliott Krause, and Carol Owen, have been consistently supportive. Students at Northeastern gave me a forum for working out some of the arguments about class and gender. The people of Isle au Haut, Maine, gave me encouragement and weekly nudges about finishing the book.

I could not have completed this book without my family. Meg and Tim Gailey, with characteristic thoughtfulness, provided me with a gentle and happy atmosphere in which to write. Adam and Eleanor saved me from hermitage with their humor and exuberance. C. K. and Stephanie, keen and interested always, lent me the money to buy a sorely needed word processor.

Suliana UluAve, Tupou Taufa, Laki Kafovalu Tonga, Manisela and Pilisita Taufoou, Soane Uata, Lafaele Vaipuna, the women of the Friendly Islands Co-operative, and their families made the field research exciting and enjoyable. I thank them for their wisdom, generosity, kindness, patience, laughter, and invaluable assistance.

I dedicate this book to my cherished mother, who wanted her children to work for the benefit of humanity; to Eleanor Burke Leacock, who forged my appreciation of the sources of authority held by women in kinship societies; and, with respect and ofa, to the women and men of the Tongan Islands, whose lives and struggles can inform our own.

C.W.G.

Boston, 1987

Introduction

WOMENS AUTHORITY and status necessarily decline with class and state formation. Class formation is a process in which groups that cut across age and gender distinctions come to have differential control over what is produced in a society and how it is distributed. At least one groupthe largest numericallyloses control over at least part of its own production or labor. In the process, one or more groups become divorced from direct engagement in the making of goods needed to reproduce the existing society. This unproductive group is dependent upon labor or goods supplied by other groups; class relations emerge if those who supply the goods and services lose the ability to determine what is produced and what is supplied. State formation is a closely related process, namely, the emergence of institutions that mediate between the dependent but dominant class(es) and the producing class(es), while orchestrating the extraction of goods and labor used to support the continuation of class relations.

The conflict between producing people, orienting their work toward subsistence, and civil authority, protecting the classes that siphon off goods and labor, is a continual, ongoing process. Most theories of state origins consider the state as a thing, with a life of its own. Further, most consider the state as a stable force in society. Profound social changeespecially state origins or revolutionbecomes difficult to explain.

Conceptualizing state formation as a process rather than a type or a category helps us to analyze historical changes and transformations of political institutions. The character of those states emerging out of kinship societies is thrown into high relief: unsystematic, often unstable sets of mediations between producing and dominant classes, that nevertheless serve to bolster the existence of the non-producing class(es). Similarly, class formation is also an inconclusive process, a changing configuration; classes can emerge, proliferate, shrink, and disappear, depending on shifts in political and economic alignments. In other words, neither class nor state formation is a one-way street. Their inherent instability creates a ground for social change, including revolutionary change.

The dynamics of class and state formation, and the declining authority and status of women, can be examined through the experiences of people in the Tongan Islands in Polynesia, a society that shifted from kinship to class relations in the course of the past 250 such as Tongan society in the period before European contact, tax, administrative, legal, and military institutionscollectively considered to be the statedo not exist. Instead, social life is ordered through kinship relations. Societies may be associated with a territory, but rights to use the resources are determined by kin and quasi-kin connections. Kinship indicates a social relationshipfictive, blood, or both. What is important is the content of the relationship, rather than its source or how it is phrased. The connection may or may not be seen as kinship: it might include such institutions as age groups and age sets, trade-friends, and other persons entering into a nexus of labor claims and expectations of reciprocity. In this definition, kinship involves reciprocal support, in the form of goods, services, and aid in life transitions. This support is generally not an equivalency; instead, the inequalities are offset through time, or through claims established by other relationships. Kinship relations are many-faceted and encompass functions that would be housed in separate religious, economic, and political institutions in our own society.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands»

Look at similar books to Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Kinship to Kingship Gender Hierarchy and State Formation in the Tongan Islands and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.