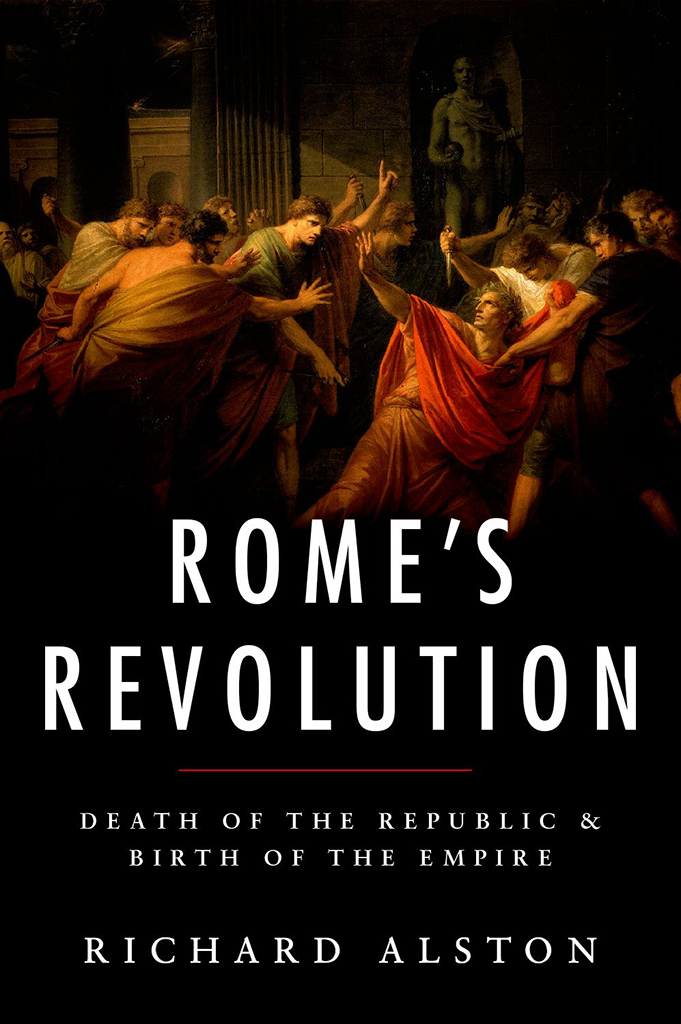

ROMES REVOLUTION

Ancient Warfare and Civilization

SERIES EDITORS:

RICHARD ALSTONROBIN WATERFIELD

In this series, leading historians offer compelling new narratives of the armed conflicts that shaped and reshaped the classical world, from the wars of Archaic Greece to the fall of the Roman Empire and the Arab conquests.

Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Greats Empire

Robin Waterfield

By the Spear: Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire

Ian Worthington

Taken at the Flood: The Roman Conquest of Greece

Robin Waterfield

In Gods Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire

Robert G. Hoyland

Mastering the West: Rome and Carthage at War

Dexter Hoyos

Romes Revolution: Death of the Republic and Birth of the Empire

Richard Alston

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Alston, Richard, 1965

Romes revolution: death of the republic and birth of the empire / Richard Alston.

pages cm.(Ancient warfare and civilization)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN9780199739769 (hardback)ISBN9780190231606 (electronic text)ISBN9780190231613 (electronic text)1.RomeHistoryRepublic, 26530 B.C. 2.RomeHistoryAugustus, 30 b.c.14 a.d.I.Title.

DG254.A47 2015

937.05dc23

2014049749

CONTENTS

ON MARCH 15TH, 44 B.C., a group of senators stabbed to death Julius Caesar. By this act, they hoped and believed, they had restored the Republic and freed Rome from the tyranny of a dictator. In fact, their actions brought an end to the Republic and ushered in a new political system, which we know as the Roman Empire. These were foundational events in Roman history. It is a matter of taste whether one emphasizes ends or beginnings, but in both ending and beginning, the events which are recounted in this book were violent, epochal, and revolutionary.

The violence of the revolution was intimate. Roman killed Roman. Family members turned against each other. The heads of enemies were displayed in the center of Rome. The dark heart of political power was there for all to see. It is this cataclysmic violence that has given historians and political thinkers pause over the centuries.

Rome was not just any state. It was a state that came to be associated with civilization, with grandeur, and with greatness. Rome has been a paradigmatic source of Western civilization. In politics, the republicanism of Rome has been long admired. At least until its last generation, Rome appeared to avoid the demagoguery and internal conflicts of classical Athens, and in so doing achieved a political stability that lasted at least four centuries and a community of purpose that brought a vast empire to this small Italian city-state. Great orators and political thinkers, such as Cicero and Cato, gave of their views as they stood before the people in the assemblies of state. This was the land of liberty and citizenship, those core values of Western political life. The historical imaginings of Romes Republic fired the English civil war against their king and French revolutionary ardor throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and inspired America to seize freedom from the remote, archaic, but powerful English monarchy.

But behind Romes idealized Republic lurks the unpleasant fact of Romes revolution, a revolution that suggested that corruption was latent in even the best of republics and moral and political decline went hand in hand with political and military success. Rome suggests that all the privileges of freedom, security, and wealth that were so hard-won over centuries of struggle could be dissipated in the blood of civil war.

This book looks once more at the trauma of the Roman revolution and attempts to understand that violent end. The problem is worth tackling not just because it was such a pivotal moment in world history, nor even because so much of our political thought since the sixteenth century has grappled with the problem of the failure of the Republic, but because, it seems to me, we have lost sight of the violence of the revolution.

In conventional historical narratives, the fall of the Republic and the birth of the empire have become bloodless, a constitutional adjustment or a worrying but brief exception in an extended golden age of rationalist, aristocratic rule. Not only does this distort events, but it civilizes them. The story I will tell here is of the fundamentals of politics: power, money, and violence.

In Western societies, we are fixated on political styles and the minor differences between our leaders. We have lost sight of the ability of power to destroy and, indeed, our reliance on political power to provide the basic necessities that get us from day to day and from generation to generation. Contemporary politics in the West is often described as dull and tedious, but if the state should fail, politics would suddenly become very interesting indeed.

The problem is one of perspective. If you are reading about the vicious violence that marks the Roman revolution in a comfortable seat in a library or lounge in Paris or Washington, London or New York, if you are warm and well fed and have no prospect of hunger or cold, then you can shudder with incomprehension and wonder at the darkness of the human soul that could tear such a system apart and bring forth anarchy onto the streets. You might shake your head at the dissipation of the freedoms of the Republic and the gradual and inexorable accumulation of power by the new imperial regime. You might thank your luck to be born in the current age, when such stories are things of the past. Or you might confine the story to the shelf of history books, remote from the realities of the modern world and with no meaning. But in many other parts of the world, if you are sitting reading this book, you may wonder what exactly the problem is: people, perfectly normal, rational people, can, under certain circumstances, take up arms and kill their neighbors. Governments, almost as a matter of course, use their resources corruptly to buy support and secure their political continuity.