THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2013 by Ramachandra Guha

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books Ltd., London, in 2013.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Guha, Ramachandra.

Gandhi before India : how the Mahatma was made / Ramachandra Guha.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-385-53229-7 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-385-53230-3 (eBook)

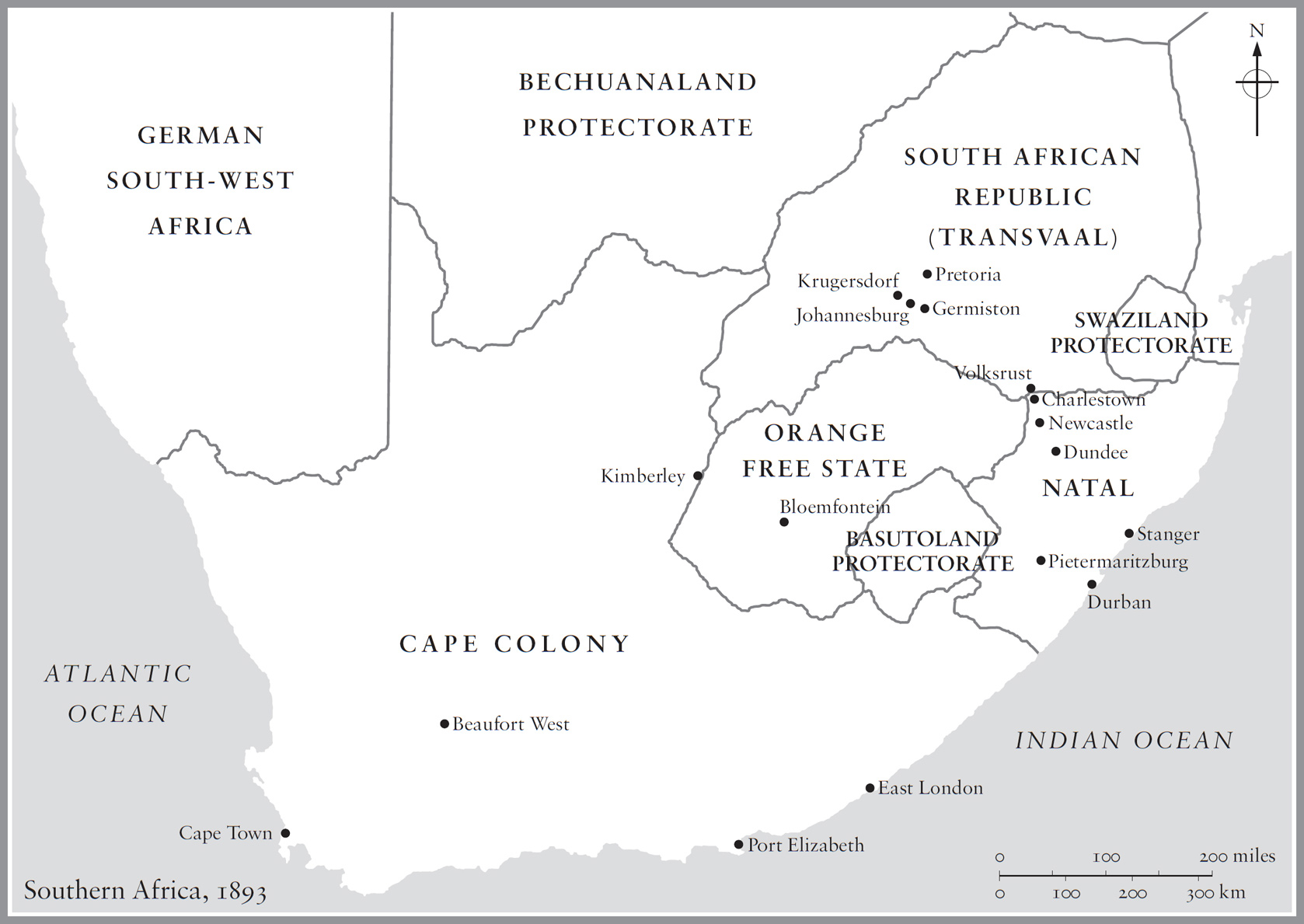

1. Gandhi, Mahatma, 18691948. 2. East IndiansSouth AfricaPolitics and government. 3. South AfricaPolitics and government18361909. 4. StatesmenIndiaBiography. I. Title.

DS 481. G 3 G 824 2014

954.035092dc23

[B] 2013025014

Cover photograph Bettmann/Corbis

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1_r1

For E. S. Reddy

Indian patriot, South African democrat, friend and

mentor to Gandhi scholars of all nationalities

Illustrations

The home in Porbandar where Mohandas Gandhi was born.

The school in Rajkot.

Karamchand (Kaba) Gandhi and Putlibai.

Mohandas, in traditional Kathiawari dress.

The Jain scholar Raychandbhai.

Gandhi as a successful lawyer in Durban, c. 1898.

A front page of Indian Opinion.

Kasturba Gandhi and children, c. 1901.

Henry Polak.

Pranjivan Mehta.

Sonja Schlesin.

Hermann Kallenbach.

Jan Christian Smuts.

Leo Tolstoy.

Gandhi in 1909.

A. M. Cachalia.

Albert West.

Thambi Naidoo.

Parsee Rustomjee.

Millie Graham Polak.

Gandhis son Harilal.

Maganlal Gandhi.

Chhaganlal Gandhi.

Contemporary cartoon of the satyagraha in the Transvaal.

Joseph Doke.

Leung Quinn.

Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Ratan Tata.

Thambi Naidoo in 1913.

Gandhi, early 1914.

Click to view a larger image.

Click to view a larger image.

I understand more clearly today what I read long ago about the inadequacy of autobiography as history. I know that I do not set down in this story all that I remember. Who can say how much I must give and how much omit in the interests of truth? If some busybody were to cross-examine me on the chapters already written, he could probably shed much more light on them, and if it were a hostile critics cross-examination, he might even flatter himself for having shown up the hollowness of many of my pretensions.

M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography,

or the Story of My Experiments with Truth

Prologue: Gandhi from All Angles

I might never have written this book had I not spent the spring term of 1998 at the University of California at Berkeley. The university had asked me to teach a course on the history of environmentalism, till then the chief focus of my research and writing. But I was tired with the subject; I suggested that I instead run a seminar called Arguments with Gandhi.

At the time, Gandhis vision of an inclusive, tolerant India was being threatened from both ends of the political spectrum. From the right, a coalition of Hindu organizations (known as the Sangh Parivar) aggressively pushed for a theocratic state, a project Gandhi had opposed all his life. On the left, a growing Maoist insurgency rejected non-violent methods of bringing about social change. To show their contempt for the Father of the Nation, Maoists demolished statues of Gandhi across eastern India.

Despite these attacks from political extremists, Gandhis ideas survived. They were given symbolic but only symbolic support by the Government of India, and more emphatically asserted by social workers and activists. The course I wished to teach would focus on Gandhis contentious legacy. However, my hosts in Berkeley were unhappy with my proposal. They knew that my contribution to Gandhian studies was close to nil, whereas a course on environmentalism would always be popular in California, a state populated by energy entrepreneurs and tree-huggers. The university worried that a seminar on Gandhi would attract only a few students of Indian origin in search of their roots, the so-called America Born Confused Desis or ABCDs.

Finally, after many letters back and forth, I was permitted to teach the course on Gandhi. But within me there was a nagging nervousness. What if my counsellors were correct and only a handful of students showed up, all Indian-Americans? On the long flight to the West Coast I could think of little else. I reached San Francisco on a Saturday; my class was due to meet for the first time the following Wednesday. On Sunday I took a walk down Berkeleys celebrated Telegraph Avenue. On a street corner I was handed a free copy of a local weekly. When I returned to my apartment I began to read it. Turning the pages, I came across an advertisement for a photo studio. It said, in large letters: ONLY GANDHI KNOWS MORE THAN US ABOUT FAST. Below, in smaller type, the ad explained that the studio could deliver prints in ten minutes, in those pre-digital days no mean achievement.

I was charmed, and relieved. A Bay Area weekly expected its audience to know enough about Gandhi to pun on the word fast. My fears were assuaged, to be comprehensively put to rest later that week, when a full classroom turned out to meet me. Thirty students stayed the distance. And only four of them were Indian by birth or descent.

Among my students was a Burmese girl who had fled into exile after the crushing of the democracy movement, a Jewish girl whose twin guiding stars were Gandhi and the Zionist philosopher Martin Buber, and an African-American who hoped the course would allow him to finally choose between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. There was also a Japanese boy, and plenty of Caucasians. In the class and in the papers they wrote, the students took the arguments with Gandhi in all kinds of directions, some of them wholly unanticipated by the instructor.

The course turned out to be the most enjoyable I have ever taught. This, I realized, was almost entirely due to my choice of subject. How many students in Berkeley would have enrolled for a course called Arguments with De Gaulle? And if an American historian came to the University of Delhi and proposed a course entitled Arguments with Roosevelt, would there have been any takers at all? Roosevelt, Churchill, De Gaulle these are all great national leaders, whose appeal steadily diminishes the further one strays from their nations boundaries. Of all modern politicians and statesmen, only Gandhi is an authentically