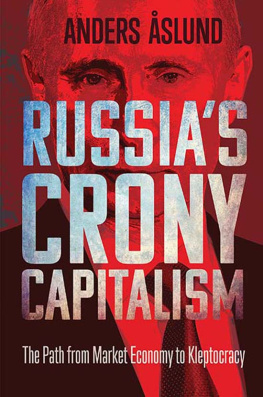

Russias

Crony

Capitalism

OTHER BOOKS BY ANDERS SLUND

Private Enterprise in Eastern Europe: The Non-Agricultural Private Sector in Poland and the GDR, 194583

Gorbachevs Struggle for Economic Reform

Post-Communist Economic Revolutions: How Big a Bang?

How Russia Became a Market Economy

Building Capitalism: The Transformation of the Former Soviet Bloc

How Capitalism Was Built: The Transformation of Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

Russias Capitalist Revolution: Why Market Reform Succeeded and Democracy Failed

How Ukraine Became a Market Economy and Democracy

The Last Shall Be the First: The East European Financial Crisis, 200810

How Latvia Came through the Financial Crisis, with Valdis Dombrovskis

Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It

Europes Growth Challenge, with Simeon Djankov

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2019 by Anders slund.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (UK office).

Set in Minion type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018957954

ISBN 978-0-300-24309-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acronyms and Initialisms

APEC | Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation |

BRICS | Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa |

CBR | Central Bank of Russia |

CEO | Chief executive officer |

CIS | Commonwealth of Independent States |

CMEA | Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (also called COMECON) |

CPSU | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

DCFTA | Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement |

EAEU | Eurasian Economic Union |

EBRD | European Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

ECB | European Central Bank |

EU | European Union |

ECHR | European Court of Human Rights |

FATF | The Financial Action Task Force |

FCPA | Foreign Corrupt Practices Act |

FDI | Foreign direct investment |

FSB | Federal Security Service |

FSO | Federal Protection Service |

FSU | Former Soviet Union |

G-7 | Group of Seven (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States) |

G-8 | G-7 plus Russia |

G-20 | Group of Twenty biggest economies in the world |

GATT | General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade |

GDP | Gross domestic product |

GNP | Gross national product |

Gosplan | State Planning Committee |

GRU | Main Intelligence Directorate |

IFI | International financial institution |

IMF | International Monetary Fund |

IPO | Initial public offering |

KGB | Committee for State Security |

NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

OECD | Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development |

OSCE | Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe |

PPP | Purchasing power parities |

Rosatom | Russian State Atomic Energy Corporation |

Rostec | Russian Technologies |

SCO | Shanghai Cooperation Organisation |

SIPRI | Stockholm International Peace Research Institute |

SVR | Foreign Intelligence Service |

USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

USSR | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

VAT | Value-added tax |

VEB | Vnesheconombank |

VTB | Vneshtorgbank |

WTO | World Trade Organization |

Russias

Crony

Capitalism

Introduction

O n December 3, 1991, I received my own office in the former Central Committee headquarters of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, at the Old Square beside the Kremlin in Moscow. It was an exhilarating moment: Russia had never been so free and open, and I was an economic adviser to the new government. Two years of intense reforms ensued in Russia, but it was only after the financial crash in 1998 that the market reforms were completed and economic growth resumed.

A quarter of a century has passed since the Soviet Union collapsed on December 25, 1991, and few now remember how free Russia was in the 1990s.

On New Years Eve 2000, the ailing president Boris Yeltsin resigned and appointed Prime Minister Vladimir Putin his successor. In March 2000, Russia held an early presidential election, which Putin won. It was Russias last competitive election.

Putin took his seat at the head of a table that was already laid with macroeconomic stability and high economic growth. His government continued reforms from 2000 to 2003, and for a golden decade, from 1999 to 2008, Russia enjoyed an impressive average annual growth of 7 percent, and the standard of living grew even more. After 1999, Russia ran budget surpluses, and the public debt dwindled.

But this happy state of affairs was not to last. In 2008, the global financial crisis hit Russia hard, and since then Russias economy has barely grownits average growth since 2009 has been just 1 percent. Putins eighteen years of rule comprise nine years of high growth and nine years of near stagnation. By the end of 2017, Putin had ruled Russia for as long as Leonid Brezhnev led the Soviet Union, and although a sense of political and economic stability prevails, so does stagnation.

Why did the Russian economy switch from seemingly sustained high growth to lasting stagnation? The standard answer is oil. Russia is a petrostate. When oil prices were high, from 2011 to 2013, oil and gas accounted for roughly two-thirds of Russias exports, half of its state revenues, and one-fifth of its GDP. But oil can be managed in many ways, by the state or by competing private entrepreneurs, and part of the answer lies in the way Putin has managed Russias vast oil and gas revenues.

Next page