Michael Gould holds a PhD from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. He has lived and worked in Nigeria and is an honorary chief of the Igbo people.

This book is an in-depth, scholarly and rigorous reassessment of the traumatic Biafran War and the making of todays Nigeria, based on the authors intimate personal knowledge of the region. One of its many strengths is its profound understanding of post-colonial Nigeria and its peoples. Another derives from the several searching interviews conducted with many of the leading protagonists. Michael Gould has written an excellent and genuinely enlightening book.

Denis Judd, Professor of History, University of

New York in London

An outstanding account and analysis of the Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Biafran War) Its profound research is based on unique personal interviews with many of the principal participants and on archival and other primary sources, which no other author has been able to access Michael Goulds outstanding study concludes with important interpretations of Biafras longevity and how far genocide was a reality or a myth, along with a notable appraisal of the history and impact of the two leaders This is a brilliant history of the Nigerian Civil War and, forty years later, stands as the best analysis yet published.

Anthony Kirk-Greene, Emeritus Fellow of

St. Antonys College, Oxford

New paperback edition published in 2013 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United Stats and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

First published in hardback in 2012 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

Copyright 2012, 2013 Michael Gould

Foreword copyright 2012 Frederick Forsyth

The right of Michael Gould to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by

the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any

part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording

or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78076 463 4

eISBN 9780857730954

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typeset by Newgen Publishers, Chennai

This book is dedicated to my late father John,

a member of the Royal West African Frontier Force.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Gowon. From Cronje, S., The World and Nigeria. (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1972)

Ojukwu. From Cronje, S., The World and Nigeria. (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1972)

Ojukwus father with his daughter (left) and the wife of Costains managing director (centre). From the private collection of Julia Burrows.

The Saudunas residence on the morning following the first coup. From the private collection of, and taken by, Simon Watson, manager, Bank of British West Africa, Kaduna.

Biafran currency. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Malnourished Biafran children. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Ojukwu inspecting a guard of honour. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Treatment of Igbo wounded at Enugu airport, following racial disturbances in the north, July to September 1966. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Photograph of an atrocity committed during the northern racial disturbances, July to September 1966. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Protest march in London to stop the Nigerian civil war. Britain-Biafra Association, Rhodes House.

Maps showing the geographical reduction of Biafra from August 1967 to April to May 1969. FCO 51/169, Public Records Office Kew.

Lt-Col. Benjamin Adekunle (The Black Scorpion), who commanded the 3rd Commando Division of the Nigerian Army.

Lt-Col. Achuzia (left), Adekunles opposite number in the Biafran Army, and Lt-Col. Morah (right), whom Achuzia threatened to shoot, after Morah had apparently absconded with two million pounds. Achuzia was ordered not to shoot Morah, but to send him back to Enugu, where he was promptly promoted.

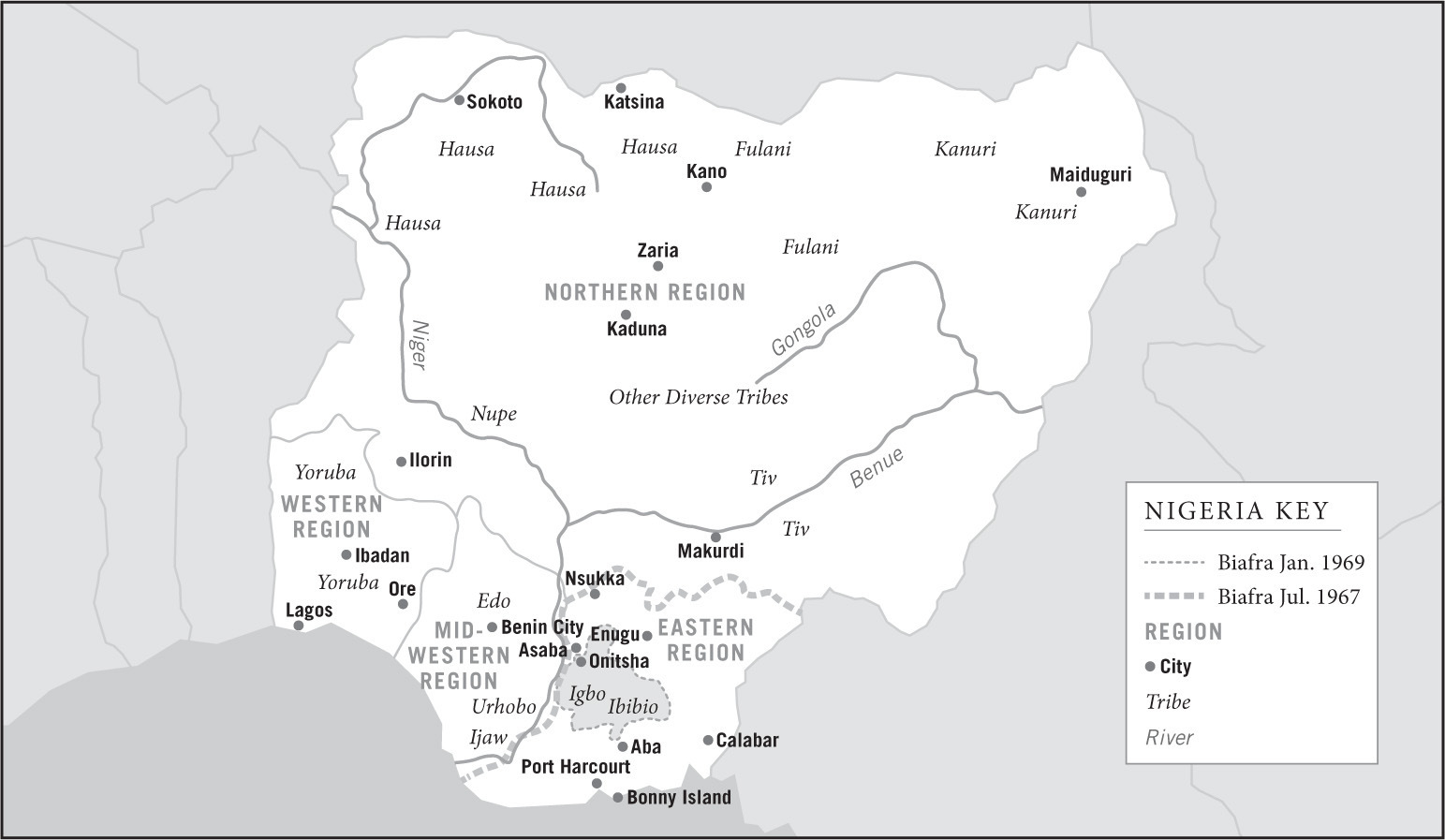

Map 1. Map of Nigeria

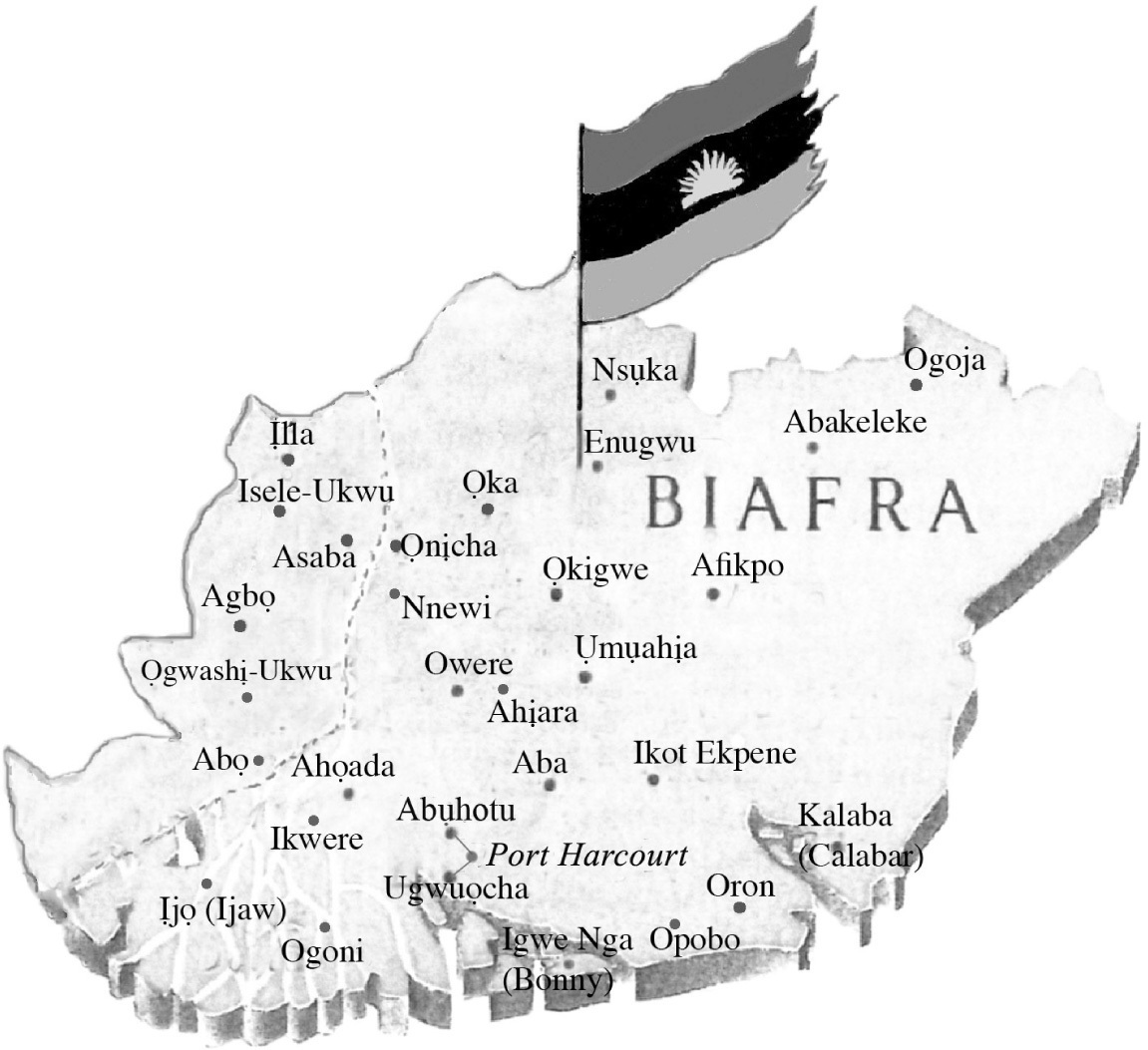

Map 2. Map of Biafra

FOREWORD

At the time of writing it has been forty years, but people still remember Biafra.

The rebellion of Nigerias Eastern Region against the Federal Government many miles away and its declaration of separate independence was supposed to be quashed within ten days by the federal army. So at least Londons Commonwealth Relations Office confidently announced.

The war lasted two and a half years, from July 1967 to January 1970. In that period an estimated number of Biafrans died, overwhelmingly children and primarily of starvation, that is generally agreed to be close to a million.

For the last year and a half, the outer world, belatedly made aware of the horror, watched and protested. In vain. There was no intervention.

But those thirty months marked two basic innovations that it took years to realise. Television war coverage came of age, and the developed world, impotent in a hundred million sitting rooms, watched their first African mass famine. Others would follow, have followed, ever since. But this was a man-made famine and no one had ever seen its like before.

Today old-stagers of the war correspondents circuit watch in awe the technology of the new craft: the brilliant colour images, in high definition, transmitted from the most obscure rock defile or jungle clearing direct to our screens at the touch of a send button. Back then it could take weeks.

Cameramen back-hauled cumbersome kit using old celluloid film. With the film finally in the can (literally a flat disc of aluminium duct-taped shut) the evidence had to reach some kind of airport. From there, perhaps in the hand baggage of a kindly missionary, it had to be flown across the world to the USA or Europe.

That was not the end. A despatch rider would take the discs to the studio for slow development into long wet strings, pegged up to dry. Finally, cut and edited, literally with a guillotine and sticky tape, the sound-track pasted to the edge, hopefully in synch, the film would make the evening newscast. It was often screened a week after being shot. In the battle-zone much could have happened, but it was the best we could do.

Much of it was in black and white, for colour stock was expensive. But for all the struggles and all the delays, those filmed reportages out of the Biafran enclave had a traumatic effect on two continents: Europe and North America. They just had not seen anything like it before.