This little book has been in the works for six years, and during that time I have run up innumerable debts. Samuel Friedman and Alexander Saxton have doubtless forgotten that the subject was formulated in conversations with them. Both provided encouragement and valuable suggestions throughout the early stages. Professor Saxton in particular was an endless fund of patience, encouragement, understanding, odd jobs, and sound advice. The work would not have gotten started without his help.

Many people in Rochester made my visits pleasant and productive. Without exception, ministers and secretaries at the churches provided places to work and access to their records. Special thanks are due to the Reverend David K. McMillan, then of Central Presbyterian Church. I hope I have treated his old friends with the respect that they deserve.

Most of the research was conducted in the Local History Room and the City Historians Office at the Rochester Public Library, and in the Manuscripts and Rare Books Division of the Rush Rhees Library at the University of Rochester. At the public library, Blake McKelvey welcomed my intrusion onto his scholarly territory, showed me his city, and allowed me to pore through a closetful of his manuscript notes. Joseph Barnes, his successor as City Historian, was unfailingly generous with his time and energy. At the University of Rochester, Karl Kabelac took an early and sustained interest in the project, and went off on his own to excavate documents thatproved to be of immense value. I am deeply indebted to his skilled detective work. Thanks are also due to the following libraries: UCLA, the University of California at Berkeley, the Henry E. Huntington Library, the Oberlin College Archives, the Arents Research Library at Syracuse University, the Regional History Collection at Cornell University, the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, the Legislative and Judicial Records Branch of the National Archives, the American Baptist Historical Society, and the Sterling and Beinecke Libraries at Yale University. The project required money as well as kindness, and for help in that area I am grateful to the Graduate Fellowship Office at UCLA and the A. Whitney Griswold Faculty Research Fund at Yale University.

My most immediate and lasting debts are to persons who criticized drafts of the manuscript. Writing is lonely and frustrating work, but many teachers, colleagues, and friends stepped in to ease its inevitable horrors. Stephan Thernstrom directed the dissertation from which the book has grown, and he has taken part in more conversations and read more drafts than he probably cares to remember. My debt to him is immense. Others who have helped include Nancy F. Cott, David Brion Davis, Richard W. Fox, Samuel Friedman, James A. Henretta, John R. Low-Beer, Lewis Perry, Roland Siu, Gene Walker, Sean Wilentz, and Allan M. Winkler. Special thanks to David Davis and Richard Fox, who gave the manuscript particularly thorough and penetrating critiques. In the spring of 1977 I presented some ideas for revision to faculty and graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh. The ideas, it quickly turned out, were wrong-headed. For the intelligence and good humor with which they pointed that out, I wish to thank David Montgomery, Seymour Drescher, and the others who were there. It was a rough afternoon, but I think the book is better for it.

In the final stages, Arthur Wang and Eric Foner labored heroically to improve the manuscript and to accelerate itsslow-moving author. They have given sound advice, and I have stubbornly ignored much of it. Like the others who have helped, I wish to thank them without implicating them in what I have done.

Occupational Groups

T HIS study looks closely into the experiences and interrelations of economic groups in Rochester during the preindustrial revolution of the 1820s and 1830s. The questions it addresses and the kinds of research that seemed most likely to produce answers demanded the collapsing of hundreds of occupations and levels of wealth into a few fairly inclusive categories. That was no simple task. Prestige rankings by occupation were useless, for the economy changed much faster than the language. Men who owned furniture factories and shoe shops called both themselves and their employees chairmakers and shoemakers. For this reason a second alternativethe ranking of occupations by mean wealthwas equally inadequate. In 1827 there were shoemakers and carpenters in every assessment decile, merchants in each of the first eight, and men in every occupation with no property at all. The problem called for the building of categories that combined the occupations and wealth of individuals, categories that both facilitated research and corresponded to real divisions in the Rochester work force. In particular, I had to find some means of separating proprietors from men who worked for wages. The following pages describe ways in which that was done.

WHITE-COLLAR OCCUPATIONS

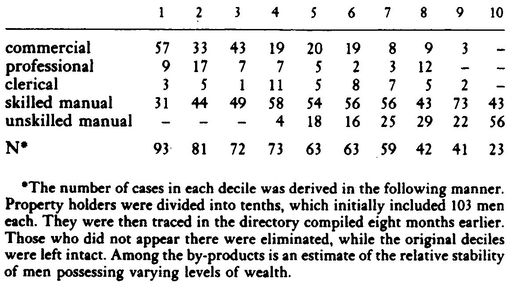

Economic data on individuals came from two sources: tax lists and city directories. Directories list the occupations of adult men. Tax lists provide a means of ranking their propertyholdings in relation to each other. provides the first indication of where that line belongs. Among the top 30 percent of taxpayers, white-collar men account for at least half the total, while below that line their numbers drop sharply. The third-decile line separates most of the men listed as merchants, lawyers, mill owners, druggists, and jewelers from those listed as grocers, boardinghouse operators, and the like.

. DISTRIBUTION OF OCCUPATIONS WITHIN ASSESSMENT DECILES, 1827 (IN PERCENT)

The property holdings of men listed with no occupation tend to verify that line. Most of these were poor and unemployed. Others were young men who had not yet gone to work, or old men who were retired. But some were wide-ranging entrepreneurs. Jonothan Child, for instance, waslisted without an occupation. Yet he owned the largest forwarding company on the Erie Canal, speculated in a wide variety of commercial ventures with his brothers-in-law, maintained a thriving legal practice, operated as agent for a number of New York City insurance companies, and managed the landholdings of his aging father-in-law, Nathaniel Rochester. Child, of course, appeared among the richest 10 percent of taxpayers. Another twenty-two men, most of them readily identifiable as successful businessmen, appeared in the first three deciles. In the fourth decile, men listed with no occupation disappear from the tax list, and with the exception of one man, they do not reappear until the eighth. Most were propertyless. It seems clear that the top three deciles separate promoters from men listed with no occupation because they really had none. Thus throughout this study I used the line between the third and fourth assessment deciles to draw the (admittedly imperfect) line between businessmen and petty proprietors.

The same line helps solve a small problem created by imprecise occupational listings. The top three deciles include a few clerks, teachers, and accountants. Evidently some clerks were partners in the stores in which they worked, or became so in the eight months that intervened between the compilations of the directory and the tax list. Some teachers owned schools, and a few bookkeepers were independent semiprofessionals. It seems proper to include those in the top 30 percent of taxpayers with the merchants and lawyers, and to relegate those who owned less property or no property to the group of clerical employees.