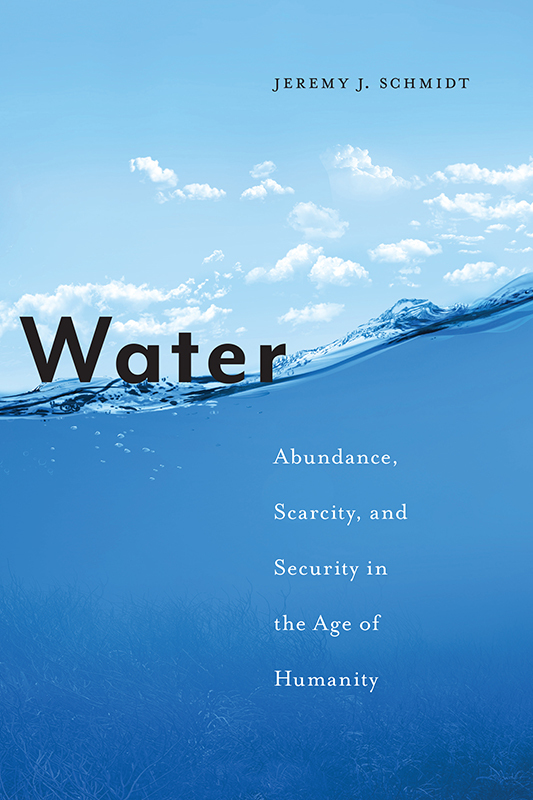

Water

Water

Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity

Jeremy J. Schmidt

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-4642-9

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To my parents, Al and Betty

The mythology may change back into a state of flux, the river-bed of thoughts may shift. But I distinguish between the movement of the waters on the river-bed and the shift of the bed itself; though there is not a sharp division of the one from the other.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, On Certainty

Contents

Adorning the foyer of William James Hall, where most of this book was written, is a quote from an essay William James wrote on the environment. It reads: The community stagnates without the impulse of the individual. The impulse dies away without the sympathy of the community. I deeply appreciate the intellectual communities, at Harvard and elsewhere, that gave the ideas in this book a sympathetic hearing. I hope, in kind, that it may provide impulse for others.

Steve Caton generously supported this project from beginning to end. The discerning voice that he brought to our many conversations significantly enhanced my scholarship. Dan Shrubsole provided the initial impetus for the book. My attempt to answer his questions about the relationship of international water decades to water management structures the text. As I revised the book, Brian Noble organized helpful opportunities to share it with colleagues. Finally, a decade ago I came from a small farm (where I hand pumped water to our animals) to McGill University. There, and since, Peter Brown has prompted me to take a much wider view of our shared planet. I thank these supervisors for their unflagging support.

Helen Ingrams work, encouragement, and example have sharpened my thinking regarding how issues of justice and equity intersect with what we are doing with, and to, water. Christiana Peppard offered thoughtful comments on the full manuscript. Comments on draft essays were offered by James Wescoat, Sarah Whatmore, Nathaniel Matthews, Elizabeth Fitting, Lindsay Dubois, Susan Flader, Caterina Scaramelli, Ramyar Rossoukh, Emrah Yildiz, and participants in Harvards 2013 Water Workshop, especially Toby Jones.

Several librarians, archivists, historians, and editors made contributions of crucial difference to this book: Cynthia Hinds and Linda Carter in the Tozzer Library were very helpful in alerting me to materials and collections, and George Clarks impeccable cataloging of Harvards Environmental Science and Public Policy Archives made research a joy. Staff at the National Anthropological Archives in Washington, DC, provided excellent insights and tirelessly searched for boxes of materials. Cris Paul and Susan Farley provided office support, kind encouragement, and often tea. Victor Baker helpfully pointed out historical connections. Jennifer Hammer and Constance Grady were immensely helpful editors and efficiently coordinated the anonymous workhorses of academia: the reviewers who read and critiqued the manuscript. I acknowledge the permissions granted by Harvard and the Smithsonian to use archival materials from the collections cited herein. Parts of Chapter 3 were previously published, and I acknowledge the Creative Commons license to my article Historicising the Hydrosocial Cycle Water Alternatives 7, no. 1 (2014): 220234. Indexing was provided by Clive Pyne, Book Indexing Services. All errors and omissions are my own. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada provided funding.

I would also like to thank Sohini Kar, who brings a singular joy to my life and work, often across large expanses of salt water and through considerable hoopla.

I dedicate this book to my parents, Al and Betty, who may very well never read beyond these acknowledgments and instead return to their concern for those less fortunate, whose lives they care for deeply and to whom they open their home and hearts. You are blessed examples.

Entering a New Era of Water Management

In 1977, California was facing a drought. By then, California water politics already bordered on legend. The Oscar-winning movie Chinatown (1974) had dramatized the politics, treachery, and straight-up lies used to appropriate this life-giving, profitable liquid. Jerry Brown, Californias youngest governor in a century, was no stranger to the drama. His father, Pat Brown, had helped to create this corrupt water dynamic in California when he was governor. The elder Brown had pulled off political sleights of hand few had had the gall to try, including misrepresenting the costs of water projects on the order of billions of dollars. This sort of subterfuge is an option when there is water to be had (or taken), but backroom deals dont count for much when there isnt. Such was the case in 1977. That year, the younger Brown convened the Governors Conference on the California Drought. He invited Luna Leopold, the first chief hydrologist of the U.S. Geological Survey and then a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, to deliver the keynote address.

Luna took the stage not only as a leading American hydrologist but also as the son of Aldo Leopoldthe ecologist whose work on soil conservation was cited when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was looking for ways to keep Americas land from blowing away during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Although Luna repeated his message time and again, he didnt hold out a lot of hope that things wouldnt get worse before getting better.

In 2015, drought returned with a vengeance to California. Jerry Brown was governor once again, this time as the oldest governor ever elected in the state. The 2015 drought, however, was different. Experts argued that it was an outcome of human actions that had changed Earths climate. So not only were the politics of water management once more unavoidable, it was also likely that the lessons learned historically might not be applicable in the future. In this context, Lunas idea of a reverence for rivers appears almost quaint, and his belief that a philosophy of water management is too complex to be developed seems obvious. The reasons abound: There are too many political, economic, and cultural values layered on top of too many water demands, often too little supply, and too many gaps in policy and knowledge. Plus, water flows. It wont sit still. It wont even stay a liquid. Waters shape-shifting ways make it too hard to ferret out what it is doing in the cavities it occupies among humans, non-humans, and the environmentlet alone to manage all of those weird spaces. At best, water management is a bricolage of ideas, norms, strategies, and techniques. In sum, as Luna argued, a philosophy of water management sounds nice, but it is just too ambitious.

Next page

![David E Newton] - The global water crisis : a reference handbook](/uploads/posts/book/104432/thumbs/david-e-newton-the-global-water-crisis-a.jpg)