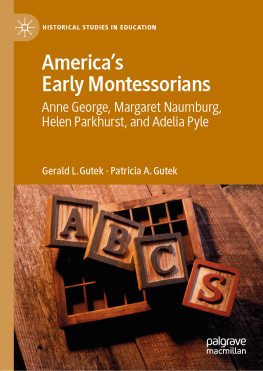

Historical Studies in Education

Series Editors

William J. Reese

Department of Educational Policy Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA

John L. Rury

Education, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA

This series features new scholarship on the historical development of education, defined broadly, in the United States and elsewhere. Interdisciplinary in orientation and comprehensive in scope, it spans methodological boundaries and interpretive traditions. Imaginative and thoughtful history can contribute to the global conversation about educational change. Inspired history lends itself to continued hope for reform, and to realizing the potential for progress in all educational experiences.

More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14870

Gerald L. Gutek and Patricia A. Gutek

Americas Early Montessorians

Anne George, Margaret Naumburg, Helen Parkhurst and Adelia Pyle

1st ed. 2020

Gerald L. Gutek

Education and History, Loyola University Chicago, La Grange, IL, USA

Patricia A. Gutek

La Grange, IL, USA

Historical Studies in Education

ISBN 978-3-030-54834-6 e-ISBN 978-3-030-54835-3

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54835-3

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Cover illustration: Lyle Leduc / Photographer's Choice RF / getty images

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

Series Editors Preface

Historians have long recognized the importance of trans-national influences upon American educational thought and practice. In the late eighteenth century, England provided the example and inspiration for the adoption of Sunday schools and charity schools. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, American reformers traveled to Prussia to observe its new pedagogical practices. And child-centered educators still study the writings of John Amos Comenius, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Johann Pestalozzi, and Friedrich Froebel. Never a single, monolithic movement, child-centered, or progressive education, was born in Europe but traveled to America before the Civil War.

Although most famous educational reformers were men, women were nevertheless central to the unfolding history of child-centered education. Over the course of the nineteenth century, white women became the majority of high school students, and they increasingly attended Americas colleges and universities. Though their salaries paled compared to mens, women were deemed superior as teachers of young children, and they formed the great majority of elementary school teachers by centurys end. Whether they appeared in private institutions, public schools, or settlement houses, kindergartens became the most important institutional expression of early childhood education and were invariably taught by women.

Americas Early Montessorians, by Gerald L. Gutek and Patricia A. Gutek, explores the history of the first attempts to establish schools inspired by Maria Montessori in the United States, which occurred in the early twentieth century. Initially trained as a physician, Montessori founded her first school in a poor neighborhood in Rome in 1907. Her instructional practices and pedagogical ideas emphasized the self-activity and sense-training of young children and soon attracted considerable attention outside of Italy. Like many innovative educators, Montessori had a magnetic personality, drawing followers from many nations. Four remarkable AmericansAnne George, Margaret Naumburg, Helen Parkhurst, and Adelia Pyletraveled to Rome and attended her teacher training program. But only a few Montessorian schools were established in America by the 1920s, and this book explains why.

The Guteks illuminate the lives and achievements of these remarkable women, including Montessori, who was unable to maintain tight control over training teachers for schools established in her name outside of Italy. Numerous obstacles blocked the establishment of such institutions in America. By the early twentieth century, kindergartens were increasingly common in many urban districts, and they were strongly endorsed by professors in normal schools and university-based schools of education. Many American progressives, including John Dewey and William Kilpatrick, criticized aspects of Montessorian instruction, believing it too closely linked to peculiar theories of child development.

Like Montessori, the four women who comprise the heart of Americas Early Montessorians were often independent thinkers. Two of them, Helen Parkhurst and Margaret Naumburg, only partially adopted the Italians ideas, which they selectively wove into their unique pedagogical plans. Parkhurst established the Dalton Plan of individualized instruction and founded a still-thriving private school in New York City. Naumburg founded the Walden School and pioneered in art therapy. Progressive schools, often privately funded, took many forms.

Maria Montessori and some of her would-be acolytes became memorable, influential figures in the history of education. Like other famous innovators, however, Montessori made educational history but not as she pleased.

William J. Reese

John L. Rury

Preface

For us, one project leads to another. Our writing of Americas Early Montessorians: Anne George, Margaret Naumburg, Helen Parkhurst and Adelia Pyle, was stimulated by our previous book, Bringing Montessori to America: S.S. McClure, Maria Montessori, and the Campaign to Publicize Montessori Education. (University of Alabama Press, 2016). When we began our work on Americas Earliest Montessorians, we had already done extensive research on the early history, the first phase of Montessori education in the United States.

Maria Montessori initially concentrated on educating children from two to six years old, at a time, 19001920, when early childhood institutions were underdeveloped in Europe and the United States. Finding traditional schools to be wholly inadequate, even miseducative, Montessori created her own unique alternative to the existing school with her prepared environment. The major institutional alternative to her method was the kindergarten developed by the German educator, Friedrich Froebel in the nineteenth century.