www.headofzeus.com

To read this book as the author intended and for a fuller reading experience turn on Use publishers font in your text display options.

Contents

For John King, BEM

Inspirational history master for forty-eight years at

St Bartholomews School, Newbury

1964 2012

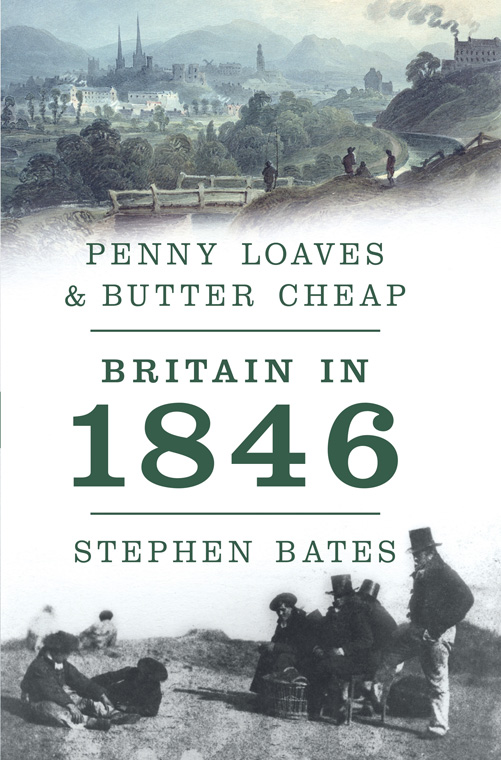

New Oxford Street had just been carved through the slums to connect the West End to Holborn and the first purpose-built five-storey blocks of flats in London were being built opposite St Pancras Old Church for improving the dwellings of the industrious classes.

It was an age of innovation. The railways were spreading along routes they still follow today, enabling people to travel for distances and to places that they and their ancestors could

In such a burgeoning, bustling society, government struggled to keep up with the pace of change, but it tried. This was the age of the inquiry and the royal commission, in which inspectors earnestly investigated every facet of Victorian life, looking into everything from sewers to cemeteries, and sought coordinated national solutions for many of the challenges and social problems thrown up by the relentless changes. Philosophical men thought they had found hygienic and efficient remedies in laissez-faire economics and utilitarian approaches to the great issues of the day, and many of their ideas about how society should be organized and conducted are still with us nearly two centuries on.

This was a country falling over itself to embrace the new and harness it. But it was also a time when many felt challenged by change, fearful that religious truths were being undermined and the old social order threatened. Even as the country raced forward, many looked back to an idyllic, pseudo-medieval past and sought to replicate a romantic image of it in their gothic buildings, their manners and their sensibilities.

And then, in the middle of this rush towards the modern age, came an enormous calamity, the worst natural disaster in the Western world since the Middle Ages: the potato famine in Ireland a catastrophe which tested the government of Britain and found it severely wanting. Not only did a million people die, but a million emigrated, altering forever the face of five countries Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia and Great Britain and affecting their relationships for generations. The famine had another effect too: it precipitated a political crisis in Britain in 1846 that permanently changed British politics and inaugurated economic policies that remained the goal of successive governments for a century to come.

At the heart of the decisions made in London in 1846 was one man: Sir Robert Peel, one of the most important and impressive figures in British political history. Having played a large part in turning the Tory party into a major electoral force following the Great Reform Act of 1832, he was then instrumental in splintering it, by the decision he took to repeal the Corn Laws. In doing so, he acted in defiance of the will of the bedrock of his party and thrust the Tories into parliamentary opposition for the following thirty years, the longest period out of government in their history. This political cataclysm realigned British parties for good: it led to the development of a new Conservative party and the creation of the Liberals out of the merger of the Whigs and Peelites, foreshadowing the politics of today. Peel strides across this narrative as the dominant personality of his time. Many of his contemporaries thought he was too; yet, if not a forgotten figure, his character is enigmatic and to us his personal style is remote and distant in both time and manner. For the best part of a century he remained a traitor to many Tories, and although he has been largely though not entirely rehabilitated in the last half-century, he remains obscure and elusive. Peel is a figure from a far-off past: a Tory, yes, and with conservative instincts, but the dominant head of a government which deliberately inaugurated some of the most far-reaching and long-lasting economic and political changes of the nineteenth century, many of them still with us today. When he died, people recognized the scale of his achievements. The Times wrote in its obituary:

If it be asked who opened the gates of trade and bade the food of man flow hither from every shore in an uninterrupted stream, it is Peel who did it... No man ever undertook public affairs with a more thorough determination to leave the institutions of his country in an orderly, honest and efficient state.

The Irish famine was a pretext for the abolition of the Corn Laws which protected British agriculture and had kept the price of food high but the decision to get rid of them was one Peel had already decided upon for other reasons. Their repeal had no significant or immediate effect on the starving populations of Ireland, or Scotland. In 1846, the decision over the Corn Laws taken largely for economic purposes had far-reaching political consequences; but it was also reached by a prime minister who was consciously motivated by a concern to improve the living conditions of a large swathe of the countrys impoverished and voteless population, and thereby to remove the causes of discontent which might lead to revolution. Violent disorder was a constant and vivid fear for the ruling classes of the country in the 1840s, for Britain was by no means the tranquil and stable state that it appears from this distance. Peels strength was to articulate the need to address directly the grievances of the poor, in a way that no previous prime minister had felt the need to do. As The Times said: if the Corn Laws had not been repealed, the whole realm of England might have borne a fearful share in [Europes] storm of wreck and revolution in 1848. Instead, that year England had an orderly Chartist protest demonstration in Kennington and a petition that called for parliamentary reform rather than revolution, peaceably delivered to Parliament by hansom cab, which MPs then ignored.

In many ways the Britain of 1846 is immeasurably different from our country today. It was a world of darkness and shadows, lit by gas lamps in some central city streets and candles in homes; a world of coal smoke and fogs in which starvation and absolute destitution existed alongside immense and heedless wealth and power; a world in which a single loaf of bread could cost a tenth of a mans weekly wage and children were still sent to work in factories and mines for twelve hours a day; a world of foul and pervasive smells and terrifying diseases far beyond the power of contemporary when gruff, shabby old J.M.W. Turner was still exhibiting at the Royal Academy and the debonair young German composer Felix Mendelssohn was conducting the premire of his great oratorio Elijah to a rapt audience at Birmingham town hall.

One hundred and seventy years have elapsed since then and yet that age is not so far away. To intrude a small personal but far from unique example: my great-grandparents, only three generations back, were alive then. In the 1840s, my fathers grandfather, David Challis, was a young wine-merchant in Leicester, having like so many others joined the exodus from the country from his familys farm, in rural north Essex, on which he had been born to the town, and he lived just long enough to hold my father as an infant in his arms for a photograph. On my mothers side, my great-grandparents were probably preparing to flee Ireland, perhaps because of the famine, and were heading east to London rather than west to the United States. The 1856 wedding certificate of William Alexander, a shoemaker aged 28 years, and Mary Sullivan, 20, a spinster, for their marriage at St Georges Catholic Church, Southwark, solemnized according to the rites and ceremonies of the Roman Catholics, is the oldest family document we still have; William signed his name but his bride and both witnesses made their mark with crosses. These folk are not quite in the memory of anyone now living, but some of them were known to people alive until recently. They may not have appreciated it at the time, but all of them lived like 26 million other British and Irish people through one of the pivotal years in the nations history: 1846.

Next page