Mark L. Haas

Duquesne University

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

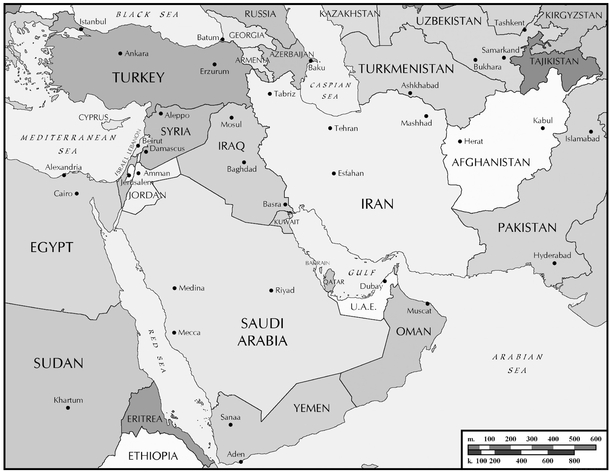

Every effort has been made to secure required permissions for all text, images, maps, and other art reprinted in this volume.

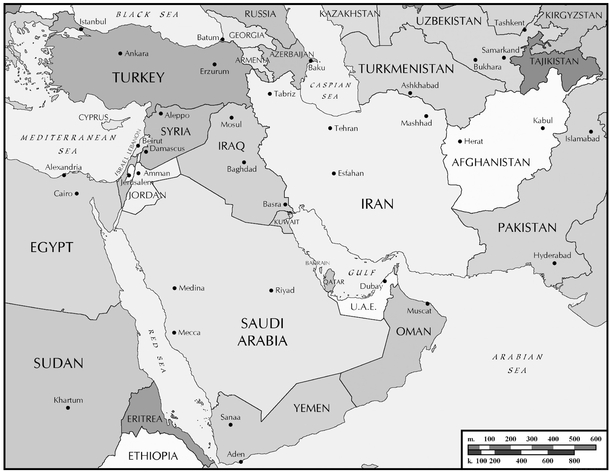

The Map Project by Justin McCarthy, Middle East Studies Association of North America, Inc. 2003

The United States and the Arab Spring

Threats and Opportunities in a Revolutionary Era

In June 2009, President Barack Obama gave a major agenda-setting speech in Cairo, Egypt. The president asserted that the spread to Muslim-majority countries of democratic governments that reflect the will of the people would be a key outcome that would make these states ultimately more stable, successful and secure. This development would also result in improved relations with the United States. Obama promised to welcome all elected, peaceful governmentsprovided they govern with respect for all their people. Given that the Middle East and North Africa at the time were widely deemed to be the least politically free regions in the world, no one expected Obamas hope for the spread of democracy at the expense of dictatorial regimes to be realized anytime soon.

Events that seemed revolutionary in every sense of the word ran counter to this expectation. Massive political protests against authoritarian governments began in Tunisia in December 2010. By 2013, protests in varying degrees of intensity, but all of major significance, had occurred in Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Syria, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen. By early 2012, dictators in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen had been forced from power, and competitive elections followed in the first three of these countries.

This chapter has three primary purposes. First, I summarize the major political consequences of the Arab Spring protests in North Africa and the Middle East. Second, I analyze how and why US leaders responded to these developments. Prominent in this analysis is a detailed examination of the threats and opportunities to US interests created by the uprisings. I conclude the chapter with a discussion of various policies the United States might adopt to best advance US security in a postArab Spring era.

I begin my analysis with an exploration of the Obama administrations reactions to the first set of Middle East mass protests that occurred during his presidency; these took place not in an Arab country but in Iran. The lessons learned from these demonstrations would have major effects on how Obama responded to the uprisings that occurred across the Arab world beginning in 2010.

Obamas Transformation: From Persian Protests to the Arab Spring

Although Obama in his 2009 speech in Cairo had called for the spread of democracy in the Muslim world, his administrations reactions to the Arab Spring beginning in late 2010 were most likely not the same as they would have been nearly two years earlier. Obama came into office believing that the George W. Bush administrations freedom agendameaning the use or threat of force to help spread liberal regimes in the Middle Easthad been a mistake. He thought his predecessors policies had resulted in a backlash against the United States that had left it isolated and reviled throughout much of the Islamic world. Thus to restore Americas reputation, it was necessary to adopt less forceful and more accommodating actions.

Obamas dominant foreign policy inclinationsespecially during his first year as presidentreinforced the conclusions resulting from the perceived failings of the Bush administration. Obamas dominant view of international relations was that what united countrieseven ideological rivalswas or should be more important to their interactions than what divided them. According to international relations scholar Henry Nau, Obama has a coherent worldview that highlights shared interests defined by interconnected material problems such as climate, energy, and nonproliferation and de-emphasizes sovereign interests that separate countries along political and moral lines. He tacks away from topics that he believes divide nationsdemocracy, defense, markets, and unilateral leadershipand toward topics that he believes integrate themstability, disarmament, regulations, and diplomacy. If shared interests are more important to states foreign policies than divisive ones, including disputes due to the effects of ideological differences, then policies of engagement should dominate Americas relations with rivals, and democracy promotion as a means of advancing US security owing to the creation of shared values with others is not paramount. This perspective helps explain Obamas call for the spread of democracy in his Cairo speech as more of a human rights than a security issue.

Occuring during his first year as president, the most important test case in the Middle East for Obamas beliefs in the power of engagement and his rejection of the use of force to alter others regimes was Iran.

Instead of supporting the Iranian protesters and the reformist political candidates they championed, Obama minimized the differences between Iranian political hard-liners and reformers. Obama officials claimed that the international policy differences between Iranian conservatives and reformers were slight. Consequently, the United States had little strategic interest in helping reformers augment their power. In a June 2009 interview, Obama stated that from a national security perspective, there was little difference for America if the hard-liner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad or the reformer Mir Hussein Mousavi won the 2009 presidential elections. Either way, asserted Obama, the United States is going to be dealing with an Iranian regime that has historically been hostile to the United States, that has caused some problems in the neighborhood and is pursuing nuclear weapons. Indeed, because Iranian reformers and conservatives were likely to pursue similar international policies toward America despite their domestic differences, in some

Obamas engagement of the Iranian regime did not succeed in improving relations. To the contrary, Irans most powerful leaders responded to Obamas overtures with contempt and threats. In reaction to Obamas videotaped message to Iran, Supreme Leader Khamenei claimed that there was no change in US-Iranian relations and that Obama had insulted the Islamic Republic of Iran from the first day.