Table of Contents

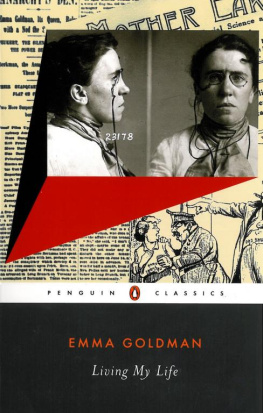

PENGUIN CLASSICS

CLASSICS LIVING MY LIFE

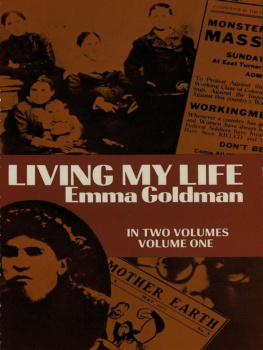

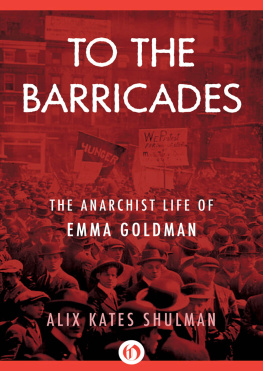

EMMA GOLDMAN (1869-1940) was a Russian-Jewish anarchist lecturer and writer who rose to prominence in the United States, the home to which she had immigrated as a young woman. A passionate orator, a defender of the struggles of labor for better working conditions, Goldman crossed America to advocate resistance to the tyranny of any form of government. Dismissive of the woman suffrage campaign, Goldman lent her support to the birth control and free-love movements. With the proceeds of her popular lectures on modern drama, she supported Mother Earth, the newspaper she founded in 1905. Mother Earth was a primary platform for anarchist theory until it was closed down in 1917, a victim of the Espionage Act of that year, making it illegal to speak disloyally of the military or to obstruct the draft. After frequent imprisonments for inciting to riot and speaking against the American entry into World War I, Goldman was deported as an alien in 1919. After her deportation, she resided temporarily in the Soviet Union, whose Bolshevik Revolution she came to regard as a tragic failure. She lived in Europe as a stateless exile, finding refuge finally in Canada at the end of her life.

MIRIAM BRODY is the editor of the Penguin edition of Mary Wollstonecrafts A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. She has written biographies of Mary Wollstonecraft (2000) and the nineteenth-century American free-love advocate Victoria Wood-hull (2003). Her other works include Manly Writing: Gender, Rhetoric, and the Rise of Composition (1993). She resides in Ithaca, New York.

Introduction

I. RED EMMA WRITES HER LIFE

The most dangerous woman in America, as J. Edgar Hoover described her, took pen in hand in June 1928 to write the events of her tumultuous life. Red Emma Goldman, who the popular press claimed owned no God, had no religion, would kill all rulers, and overthrow all laws, chose to begin her autobiography on her fifty-ninth birthday, a task she would later say was the hardest and most painful she had ever undertaken (Goldman, Nowhere at Home, 145). As she wrote about her life, she confronted not only her own loneliness but also the disappointment of her political hopes, the dream that anarchism, which she called her beautiful ideal, would take root in her lifetime among the people whose benefit she believed she served.

Others had urged her to begin her memoir years before, but she had been busy traversing the country, lecturing, organizing, writing, or if in prison, forging bonds with other inmates, protesting conditions, or alerting vast networks of supporters and friends to crises imminent or arrived. Now in a borrowed cottage in the south of France, years advancing, living on funds raised by friends and a generous advance from her American publisher, Emma Goldman began a labor that would require three years to complete, writing in longhand by night and dictating to a typist by day. I am anxious to reach the mass of the American reading public, she wrote to a friend, not so much because of the royalties, but because I have always worked for the mass (Drinnon, 269). In fact, she was writing also in her own interest, hoping to win the sympathy of American readers who might help reverse the decision to deport her that had left her a stateless exile.

Eight years earlier, in 1920, America, her adopted country, had deported her as a subversive, leaving her feeling an alien everywhere, as she wrote to her friend in exile Alexander Berkman (Nowhere at Home, 170). A permanent, often unwelcome guest in someone elses country, she would infuse her writing with a sense of loneliness and despair. To Berkman she wrote hardly anything has come of our years of effort (ibid., 49). On the eve of fascist victories in Europe, she felt as well the nearness of catastrophe, the likelihood that once again, as it had in 1914, Europe would be convulsed by war.

Underlying this sense of impending disaster, she was aware that political radicals on the left were embracing the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, a revolution she believed had betrayed the expectations of the Russian peasants and workers in whose name Lenins government served. She had spent two years in the new Soviet state, having gone there as an anarchist victim of the infamous Palmer raids that launched the first widespread red scare at the time of Americas entry into World War I. Instead of meeting the intoxication of a liberated society that had thrown off the shackles of czarist autocracy, Emma Goldman found, she believed, a dispirited and growing Bolshevik state. To her dismay, the state was consolidating its powers, responding, she felt, incompetently and calamitously to its economic and political crises and, to compound the disaster, imprisoning and executing its dissidents.

Russia had been her birthplace in 1869, but more important, Russia had nurtured the revolutionary beliefs she had taken as a young immigrant girl to America. At sixteen, she had joined the thousands of refugees from eastern Europe, many fleeing the Russian anti-Semitism that broke out in violent pogroms in the eastern pale of settlement after terrorists assassinated Czar Alexander II. Now disappointed by Russia, Emma Goldman trained her hopes once more on the American shores, where she had left behind friends and family.

Writing her life story might have proved difficult. She had kept no diary. Although there had been a vast record of her writing and lecturing stored in the offices of Mother Earth, the journal she founded in 1905 and maintained through many busy years, these records had been destroyed by federal agents who systematically ransacked and looted the property of political radicals. Fortunately she had been a faithful and copious letter writer, and in response to her request more than a thousand of these were returned to her. Some letters to friends were meticulous accounts of her prison yearswhat she read, what she was fed, the gifts sent to her by loyal supporters, the campaigns she carried on for better conditions, the relations formed with other inmates. Other letters could provide testimony enough for her to recall her public life, years in which she was both witness to and a principal actor in the political convulsions that defined her timeworkers strikes, riots, assassinations, the womens rights movement, political repression, revolution, and exile. Five hundred more letters came from Ben Reitman, the man who had been for many years her publicist, road manager, and lover. In these she chronicled a response to a love affair in which she berated Reitman for betrayal, soothed his vanity when he was snubbed by the anarchist luminaries he hoped to impress, or frankly recalled the pleasures of his bed.

Goldmans was a rich life to chronicle, the story of an intellectual and emotional journey of a Russian woman who became an American original, someone who combined the radical political traditions of nineteenth-century Europe with the insurgent individualism of the young American republic. The fusion she sought was an anarchism responsive to the changes in America in the early twentieth century, an anarchism that would transform the conditions of public and private life. To the call for radical reorganization of work life she inherited from European political tradition and to the conviction in the supremacy of individual liberty she found in the American literature of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman, Goldman added advocacy of the birth control and free-love movements that had emerged out of nineteenth-century American anarchist and utopian communities. Without such reforms, she would argue, there would be no egalitarian emancipation of the whole of humanity.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS