Table of Contents

Also by Peter Glassgold

AUTHOR (FICTION)

The Angel Max (1998)

EDITOR

James Laughlin, Byways: A Memoir (2005)

Living Space: Poems of the Dutch Fiftiers (1979; rev. ed., with Douglas Messerli, 2005)

New Directions in Prose & Poetry, joint editor with James Laughlin,

nos. 2555 (197291)

EDITOR/TRANSLATOR

Boethius: The Poems from On the Consolation of Philosophy, Translated out of the original Latin into diverse historical Englishings diligently collaged (1994)

Hwaet! A Little Old English Anthology of American Modernist Poetry

(1985; rev. ed., 2012)

TRANSLATOR

Hans Deichmann, Objects: A Chronicle of Subversion in Nazi Germany and FascistItaly, translated with Peter Constantine, from the German (1997)

Stijn Streuvels, The Flaxfield, translated, with Andr Lefevere, from the Dutch (1989)

For Suzanne

and to the memory of

Paul Avrich

PREFACE

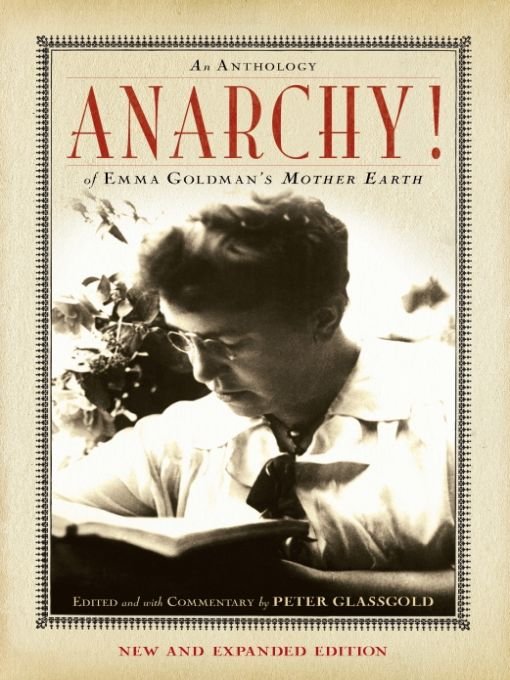

This new, expanded edition of Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldmans MOTHER EARTH was conceived in an uneasy time, while the earlier edition, published before the attacks of 9/11, was born out of plain curiosity and a writers need. Lets first consider the nearer anxieties and then how they relate to American anarchism of a previous troubling era.

The year 2012 found America struggling to recover from the greatest financial collapse since the Great Depression, following its engagement in two lengthy, expensive wars, amid protest on the right and left, political dissension and near paralysis, all under the generally dawning realization that the country was experiencing a dangerous imbalance of national wealth not seen since the turn of the last century, the time when anarchism and other revolutionary causes were at their prime. What, if anything, did the conservative and progressive protesters have in common with each other? The answer, it seems to me, is clear. Both movements were loosely organized and drew from the ranks of a disaffected middle class that saw its prospects steadily diminishing, and both were libertarian in the Jeffersonian sense of that government is best that governs least. Beyond that, the gulf between them was immense, with the conservative, largely middle-aged Tea Partiers, insofar as they had a uniform agenda, being antitax, anti-union, antiabortion, vocally patriotic and promilitary, largely secular but in rapport with a determined religious minority, as well as increasingly nativist and disbelieving in global warming and other environmental concerns positions familiar and generally agreeable to the contemporary American far right.

On the progressive left stood Occupy Wall Street (OWS) and its independent offshoots nationwide, whose direct action brought to public consciousness that one percent of the American population controlled more than one third of the wealth, hence the rallying cry, We are the 99%! What, if anything, did Occupiers have in common with their dissident forebears of yesteryear? Their prolonged sit-ins certainly evoked the evolving methods, generally peaceful, of civil disobedience and protest begun in the days of Abolition and continued onward through Emma Goldmans time to the era of Vietnam, the nonviolent civil rights movement, and beyond, which called into question existing state institutions and the legitimacy of the legal system itself. Occupiers, mostly young, organized themselves as miniature communal societies based on the self-regulating counsel of direct democracy, as if to announce that such social harmony as theirs was an example to the world. It was a model of the leftwing libertarianism argued for in the pages of Mother Earth, but was it, in fact, in line with anarchist tradition? Here, a capsule historical survey is helpful.

The modern idea of political revolution resonates back to the American and French revolutions, which replaced monarchical and imperial rule and its attendant aristocracy with republican government. To this was added over the course of the nineteenth century the concept of nationalism; revolutions often became, in effect, unifying wars of liberation. However, a third idea had also begun to accrue to the idea of revolution, that of radical social and economic change brought on by an international upheaval of workers and peasants. A hundred years ago, when someone referred to the coming revolution, this last was the one that was meant, and it remains at the heart of anarchism then and now. The anarchist movement in America, initially shattered by the red scare of 191920 and depleted by defections to the Communist Party in consequence of the Bolshevik ascendance in Russia, nevertheless survived the century, though fragmented as always, drawing back from the expectation of imminent revolution and instead preparing the way to the future social order, with the main emphases on education and the environment in the here and now.

In the light of such history, what then of the Occupy movement? It was, as Ive said, loosely organized, with no central coordination of any kind. But lets consider one unofficial OWS website, which displayed on its home page the traditional revolutionary workers clenched fist, with the catchword, The revolution continues worldwide! Below that was a list of typical demands, among them a guaranteed living wage, a single-payer health care system, free college education, accelerated development of a green economy free of fossil fuels, an equal rights amendment respecting race and gender, open borders, debt forgiveness and the outlawing of collection agencies, and eased restrictions on unionization and collective bargaining. For sympathizers on the left, of which I count myself one, these are familiar and agreeable positions, none of them new, some more radical than others, but not essentially revolutionarymany have been tried successfully beforenor even socialist. The fact is, we are not living in an era of working-class and peasant revolt. Present-day revolutions are against authoritarian rule of whatever stripe, calling for regime change, not the end of capitalism itself. In relation to anarchism, OWS demands strike me as strictly reformist, which, to my mind, is by no means a bad thing. However, in the stateless society envisioned in Mother Earth, one with not less government but no government at all, and in which, by definition, essential services are free, a constitutional amendment would be no more relevant than a single-payer health care system. OWS was surely a descendant of anarchism, its strategies taken enthusiastically from the social libertarian playbook, but calling it anarchist as such seems to me a forgivable misapprehension of the word for which, perhaps, this book may stand as a corrective. For looking at matters from the long-term anarchist perspective, the course of history and true revolution never did run smooth.

Turning now to the first edition of Anarchy! (2001), it was, as I noted earlier, born of curiosity and need, a set of circumstances that has not changed much in the ensuing years. References to