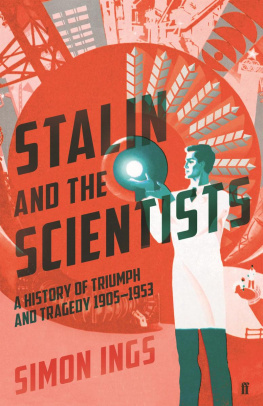

STALIN

AND THE

SCIENTISTS

Also by Simon Ings

fiction

HOT HEAD

HOTWIRE

HEADLONG

CITY OF THE IRON FISH

PAINKILLERS

THE WEIGHT OF NUMBERS

DEAD WATER

WOLVES

nonfiction

THE EYE: A NATURAL HISTORY

STALIN

AND THE

SCIENTISTS

A HISTORY OF TRIUMPH

AND TRAGEDY 19051953

SIMON INGS

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2016 by Simon Ings

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

Printed in the United States of America

First published in 2016 in Great Britain by Faber & Faber Ltd.

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: February 2017

ISBN 978-0-8021-2598-9

eISBN 978-0-8021-8986-8

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For my children

Leo, whose every Christmas, more or less, has been spent

under a tree topped with a hand-fashioned cardboard Stalin,

and Natalie, who supplied the glue for same.

Contents

Fuses (18561905)

: CONTROL (19051929)

POWER (19291941)

DOMINION (19411953)

Spoil

Illustrations

Soviet citizen science: an air velocipede invented by a worker in Moscow. Bettmann/Getty

Vladimir Vernadsky and friends at St Petersburg University. Courtesy of Synergetic Press/The Commission on Elaboration of Scientific Heritage of Academician V. I. Vernadsky, Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Vladimir Lenin plays chess with Alexander Bogdanov, 1908.

Paul Dirac and guests of the Sixth National Congress of the Russian Association of Physicists sail down the Volga. AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives

Biometric studies at Alexei Gastevs Central Institute of Labour.

Vsevolod Pudovkins film Mechanics of the Brain: The Behaviour of Animals and Man popularised Ivan Pavlovs physiology as a materialist science.

Scene from Salamandra (1928), a film based on the life and work of Austrian Lamarckist biologist Paul Kammerer. 113

Part of the collection of the Moscow Brain Institute. Courtesy of Alla A. Vein

A model of the Magnitogorsk steel works, on display at the 1939 Worlds Fair in New York. Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images

News of show trials reaches the factory floor, 1936. Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images

Ivan Michurin and an assistant. Sputnik/Science Photo Library

A collection of wheat from the Bureau of Applied Botanys collection. Sputnik/Alamy

Children in Donetsk dig potatoes out of the frozen ground.

Nikolai Timofeev-Ressovsky, Cecile and Oskar Vogt, and Hermann Muller in Berlin.

Trofim Lysenko measuring the growth of a wheat crop. Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

Nikolai Vavilov in a prison photograph.

Young men and women parade a papier mach harvest across Red Square. Framepool

At the Volkovo cemetery, men bury victims of Leningrads siege. Sputnik/Alamy Stock Photo

Yulii Khariton sits beside a copy of the first Soviet atomic bomb.

The August 1948 Session of the Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Courtesy of RGAKFD

A cartoon by Boris Yefimov casts genetics in a fascist guise.

A 1949 poster shows Stalin drawing up new forests to change the Russian climate. Courtesy of Stephen Brain

Nikolai Timofeev-Ressovsky and the mathematician Alexei Liapunov. Nauka Press/V. I. Ivanov/N. A. Ljapunova

A ship rusts away in what was once the Aral Sea. Courtesy of P. Christopher Staecker

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers would be pleased to rectify any omissions or errors brought to their notice at the earliest opportunity.

Preface

Come, brethren, let us look in the tomb at the ashes and dust, from which we were fashioned.

Verse from the Orthodox burial service

This book about more or less the whole of scientific life in the Soviet Union, from its birth until the mid-1950s grew out of my fascination with someone other than Joseph Stalin.

Alexander Romanovich Lurias classic neuropsychological case study The Mind of a Mnemonis t was one of the first books of modern popular science: a slim book that shaped a genre. In it, Luria described the strange world of Solomon Shereshevsky, a man with a memory so prodigious it ruined his life.

Some years ago I met another Luria obsessive who wondered aloud if there was room for a new biography. I did some research and hit a wall. Lurias most astonishing achievement, in a career full of astonishing achievements, was his ability to lead a normal life. He betrayed no one, nor was he betrayed. He led a happy family life and enjoyed many close friendships with colleagues abroad. His work was as sound as it was brilliant. Lurias life and work are endlessly fascinating from a scientific point of view but, for a biographer, there is little to tell that has not already been told.

Yet here was a man a Jew in a country goaded by the state into anti-semitism who exposed himself again and again to political risk, who was repeatedly interrogated, sacked and admonished, whose work was forever being banned. Lurias career was an extraordinary demonstration of Winston Churchills adage that success consists of moving undaunted from failure to failure.

To unpick the ambiguities of Lurias quiet life, I realised I would need to explore Lurias world, and the more I explored, the more I came to appreciate the generation from which Luria sprang: young men and women who grew up in revolutionary times and whom Stalin and his government had not yet cowed into obedience.

So this has become a much bigger story: it describes what happened when, early in the twentieth century, a motley handful of impoverished and under-employed graduates, professors and entrepreneurs, collectors and, yes, charlatans, bound themselves to a failing government to create a world superpower.

Russias political elites embraced science, patronised it, fetishised it and even tried to impersonate it. This process reached a head in 1939 when the supreme patron of Soviet science established a prize in his own name for scientific research, the Stalin Prize. At the same time, the supreme national scientific institution, the USSR Academy of Sciences, elected him an honorary member.

Suspected, envied and feared by the Great Scientist himself, scientific disciplines from physics to psychology, genetics to gerontology (a Soviet invention) sought to avert the many crises facing the country: famine, drought, soil exhaustion, war, rampant alcoholism, a huge orphan problem, epidemics and an average life expectancy of thirty years. Their work, writings and wrangles with the political authorities of their day shaped global progress for well over a century.