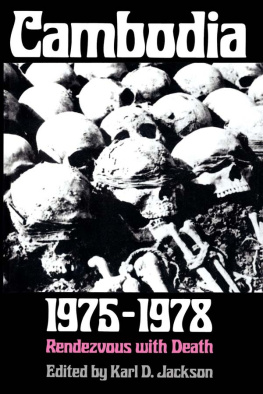

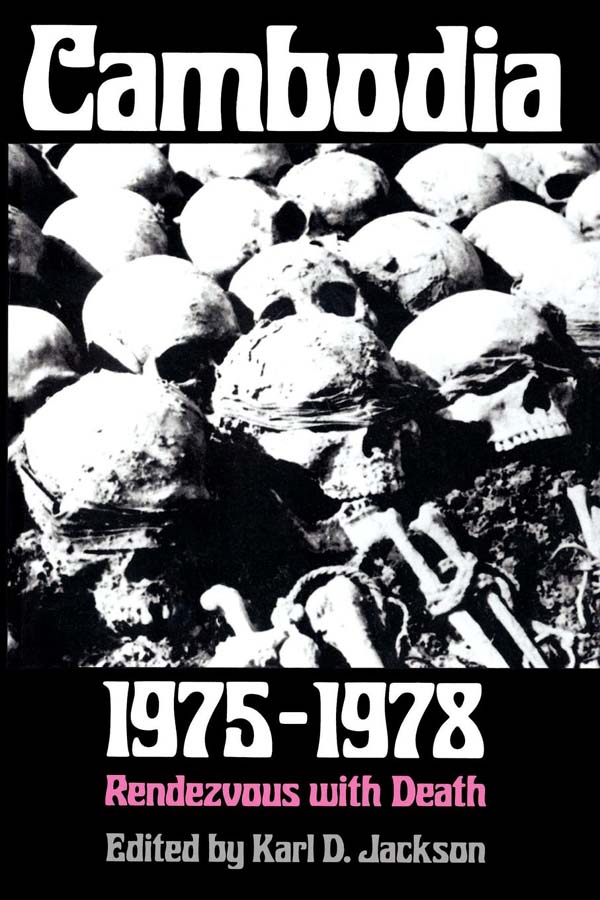

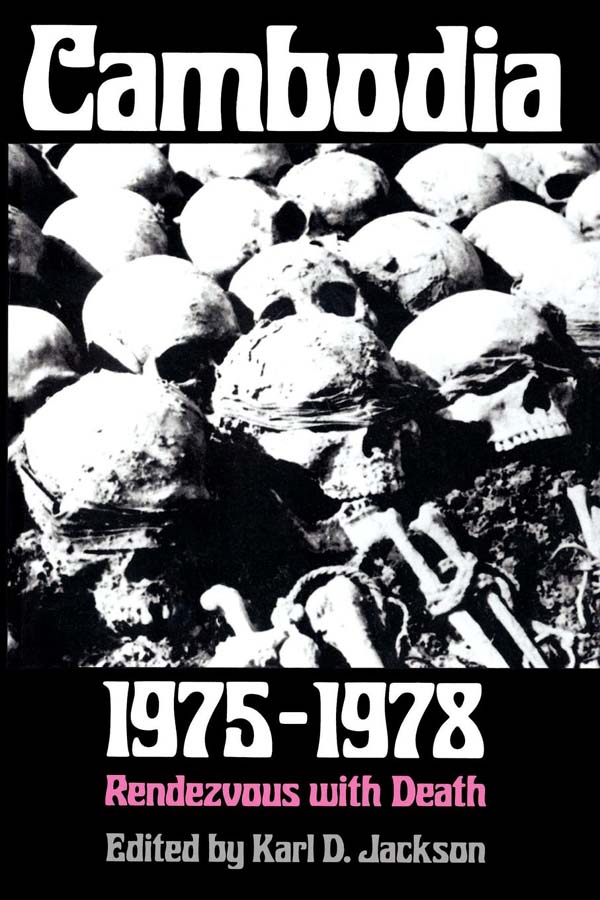

Cambodia 19751978: Rendezvous with Death

CAMBODIA 19751978

Rendezvous with Death

KARL D. JACKSON

Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey

Copyright 1989 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

This book has been composed in Linotron Aldus

Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cambodia, 19751978 : rendezvous with death / [compiled by] Karl D. Jackson,

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0691078076

ISBN 069102541X (pbk.)

1. CambodiaHistory1975 I. Jackson, Karl D.

DS554.8.C357 1989

959.6'04dc19

8826764

9 8 7 6 5 4

This book is dedicated

to Lucian W. Pye

Teacher, Scholar, and Friend

Contents

Preface

A year of sabbatical leave in Thailand, generously financed by the Henry Luce Foundation, led to this volume. During 19771978 the Khmer Rouge frequently raided Thai villages and simultaneously involved themselves in a war with Vietnam. However, the single most interesting topic that year derived from the sense of mystery concerning what was transpiring within Democratic Kampuchea. Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution by Gareth Porter and George Hildebrand (1976) contended that the tales of political bestiality and economic catastrophe were a hoax. In contrast, Murder in a Gentle Land by John Barron and Anthony Paul (1977) and Cambodia: Year Zero by Franois Ponchaud (1978) depicted an extremely violent and perhaps autogenocidal revolution. Clearly both versions could not be true. What, in fact, was happening just beyond the Thai-Cambodian border?

Upon returning to the United States I realized that the task of explaining the Cambodian revolution exceeded my own knowledge and that, if possible, I should gather together a group of persons with unique experience and expertise. This led to the selection of the authors whose chapters comprise this study. Rather than asking them merely to contribute their latest writing on Cambodia, I sought to design a book that would illuminate the most salient dimensions of revolutionary Cambodia: how the revolutionaries came to power, what they believed in, their organizational structure, the economic system, social and religious life, and the pattern and origins of the violence of their rule.

Timothy Carney had lived in Cambodia from 1972 to 1975, while serving as a political officer at the American Embassy. After 1975, he published a monograph on the communist party in Kampucheabefore the Kampuchean communists had even admitted their adherence to that doctrine. By experience and expertise, he seemed the logical choice for composing the chapters on how the Khmer Rouge came to power and the resulting party structure. Another foreign Service officer, Charles Twining, came to my attention because of the careful work he had done in interviewing Khmer refugees in Thailand. The knowledge he garnered made him ideal for describing and explaining Kampuchean economic life. Kenneth Quinn spent two years in Vietnam living just across the border from Cambodia and composed a remarkably prescient report for the U.S. State Department in 1974, a time when many Americans and Cambodians alike were reluctant to accept the reality described to Quinn by those early Cambodian refugees from Khmer Rouge rule. His interest in the patterns and intellectual origins of violence led not only to his chapters in this book but also to a dissertation. Franois Ponchauds unique knowledge of Cambodian society and culture made his contribution essential to the volume. My own chapters grew from a fascination with what the Khmer Rouge leaders were attempting to achieve. What peculiar brand of ideology and circumstance minted the alloy of historys most violent revolution? Words alone bear insufficient witness to the human toll exacted by history. For this reason David Hawks photographic essay describes, perhaps with greater intensity than other chapters, the impact of the revolution on the Cambodian people. Finally, primary source documents on the Khmer Rouge remain scarce, at least in English translation, and I therefore included several hitherto unavailable articles provided by Timothy Carney.

THIS STUDY would not have been possible without a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to the Institute of East Asian Studies of the University of California, Berkeley. The project greatly benefited from the advice and help of Martha Wallace and Robert Armstrong, executive directors of the Luce Foundation, and Robert A. Scalapino, director of the Institute. In addition, numerous colleagues at Berkeley provided advice, including A. James Gregor, Kenneth Jowitt, William Muir, and Aaron Wildavsky. Finally, I would like to thank Rhonda Brown, Gerard Mar, Susan Barnes, and Steve Denney, who served ably as research assistants during various phases of the project.

THROUGHOUT the manuscript Kampuchea and Cambodia have been used interchangeably. When the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia, between 1975 and early 1979, the world conformed to their usage, Kampuchea, whereas Cambodia was the countrys accepted name before 1975 and resumed its place after 1979.

THE PHOTOS and illustrations in are from the collection of David Hawk. Unless otherwise indicated, they were taken by Hawk himself and are reproduced here with his permission.

is reproduced, by permission of the publisher, from Laura Summers, The CPK Secret Vanguard of Pol Pots Revolution, Journal of Communist Studies 3 (March 1987), pp. 1415.

Cambodia 19751978: Rendezvous with Death

Introduction. The Khmer Rouge in Context

by Karl D. Jackson

More than one million people are dead to begin with. Included are not only the victims of Pol Pots killing fields, where members of the former ruling elite were cut down, but also, hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children who died from disease and starvation directly resulting from the regimes misguided and draconian policies.

Out of 7.3 million Cambodians said to be alive on April 17, 1975, less than 6 million remained to greet the Vietnamese occcupiers in the waning days of 1978.). Pol Pots regime purged and repurged itself in a fratricidal search for ideological purity and internal security. In the end, striving for security at any price proved counter-productive; the government fundamentally alienated its people, frightened critical cadres into an alliance with Vietnam, and weakened the country to the point that it could offer little organized resistance when Democratic Kampuchea faced the third and conclusive invasion from Vietnam in late December 1978.

Starvation and pestilence stalked the land because the regimes pursuit of complete independence led it to sever access to most aid and trade, thereby insuring death-dealing shortages of food, pesticides, and modern medicine. Successful communist revolutions emphasize national sovereignty and self-reliance, but no other movement has applied the academic theory of dependency in such a doctrinaire and literal manner, thereby inflicting on Cambodia severe diplomatic isolation, economic devastation, and massive human suffering. Likewise, aspiring revolutionaries have been wont to displace ruling bureaucratic and military elites of the ancien rgime; however, no previous revolutionary elite has moved so relentlessly to hunt down and kill as many as possible of the trained and educated manpower necessary to staff a state. Standard revolutionary practice has been to establish the regime first, eliminating the prerevolutionary elite only after revolutionary replacements have been trained; instead, the Khmer Rouge eliminated the functional elite or drove them out of the land, disregarding the absence of replacements. Similarly, revolutionaries have often cursed the clergy, but political pragmatism has usually precluded the type of policies adopted by the Khmer Rouge, namely, immediate disestablishment of the national religion, death to its elders, and desecration of its revered monuments.

Next page