Copyright 2020 by Jonathan Sacks

Cover design by Chin-Yee Lai

Cover copyright 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Hodder & Stoughton

First US Edition: September 2020

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sacks, Jonathan, 1948- author.

Title: Morality : restoring the common good in divided times / Jonathan Sacks.

Description: First US edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020022056 | ISBN 9781541675315 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541675322 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ethics. | Common good.

Classification: LCC BJ1012 .S235 2020 | DDC 170/.44--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020022056

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-7531-5 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-7532-2 (ebook)

E3-20200723-JV-NF-ORI

Not in Gods Name: Confronting Religious Violence

The Great Partnership: God, Science and the Search for Meaning

Future Tense: A Vision for Jews and Judaism in the Global Culture

The Home We Build Together: Recreating Society

To Heal a Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility

From Optimism to Hope: A Collection of BBC Thoughts for the Day

The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilisations

Radical Then, Radical Now: On Being Jewish (in USA, A Letter in the Scroll)

Celebrating Life: Finding Happiness in Unexpected Places

The Politics of Hope

The Persistence of Faith: Religion, Morality and Society in a Secular Age

One People? Tradition, Modernity and Jewish Unity

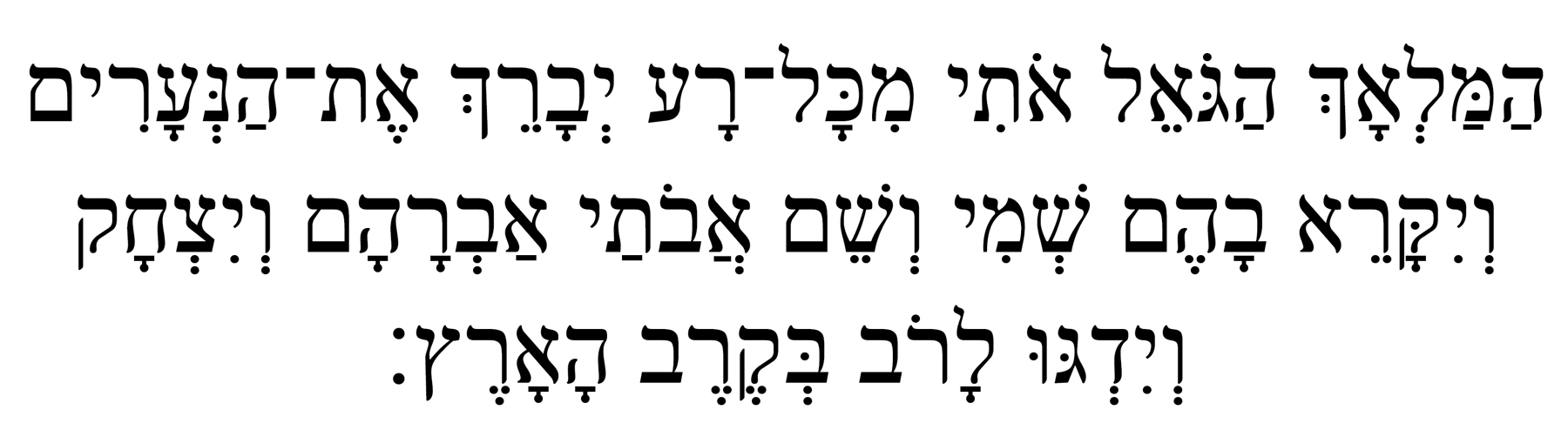

To our grandchildren:

Noa, Ari, Elisha, Gedalya, Zev,

Ariella, Natan, Talya, and Noam

(Gen. 48:16)

May all you do be blessed

T HE JOURNEY of which this book is the culmination began more than fifty years ago. Although I have spent much of my adult life as a religious leader, my first love, long before I decided to become a rabbi, was moral philosophy, which I studied at both Cambridge and Oxford. I was incredibly blessed to have as my tutors three of the greatest philosophical minds of our time. My third-year undergraduate tutor was Roger Scruton. My doctoral supervisor at Cambridge was Bernard Williams and at Oxford, Philippa Foot.

They were outstanding. But the state of moral philosophy in general was not. It was clever but not wise. A. J. Ayer told us, in a famous chapter of Language, Truth and Logic, that moral judgments, being unverifiable, were meaningless, the mere expression of emotion. Another philosopher told us that ethics was a matter of inventing right and wrong. Moralityso went the popular viewwas either subjective or relative, and there was little in academic philosophy of the time to say otherwise. James Q. Wilson, the great Harvard political scientist, discovered, while teaching a class on Nazi Germany, that there was no general agreement that those guilty of the Holocaust had committed a moral horror. It all depends on your perspective, one student said.

All three of my teachers knew that there was something wrong with all of this. It was superficial, philistine, and irresponsible. Each found a way out, though it took time. Bernard Williams told me in 1970 that he did not know how to write moral philosophythough he quickly recovered and produced his first book, called, like this one, Morality, in 1971. I had meanwhile decided that the best place to begin was within my own tradition of Judaism, which has had an almost unbroken conversation on the nature of a good society since the days when Abraham was charged to teach his children the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just (Gen. 18:19).

There were others who could see what was going wrong. Philip Rieff said that culture is another name for a design of motives directing the self outward, toward those communal purposes in which alone the self can be realised and satisfied, and that this was now being systematically abandoned in pursuit of what he called the triumph of the therapeutic.

For me, the most persuasive was Alasdair MacIntyre and his masterwork, After Virtue, in which he argued that though we continue to use moral language, we havevery largely, if not entirelylost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality. I prefer hope.

Love your neighbor. Love the stranger. Hear the cry of the otherwise unheard. Liberate the poor from their poverty. Care for the dignity of all. Let those who have more than they need share their blessings with those who have less. Feed the hungry, house the homeless, and heal the sick in body and mind. Fight injustice, whoever it is done by and whoever it is done against. And do these things because, being human, we are bound by a covenant of human solidarity, whatever our color or culture, class or creed.

These are moral principles, not economic or political ones. They have to do with conscience, not wealth or power. But without them, freedom will not survive. The free market and liberal democratic state together will not save liberty, because liberty can never be built by self-interest alone. I-based societies all eventually die. Ibn Khaldun showed this in the fourteenth century, Giambattista Vico in the eighteenth, and Bertrand Russell in the twentieth. Other-based societies survive.

Morality is not an option. Its an essential.

T HIS BOOK was written before the coronavirus pandemic and published in Britain just as it was reaching these shores. Yet it spoke to the issues that arose then: the isolation many suffered, the selfless behaviors that allowed life to continue, the self-restraint we had to practice for the safety of others, the realization that many of the heroes were among the lowest paid, the challenge of political leadership in time of crisis, and the importance of truth-telling as a condition of public trust. These are all moral issues, and I explain in the newly written Epilogue how their significance suddenly became vivid. I hope that, in the context of a post-pandemic world, the book might serve as a guide to how, after a long period of isolation, we might think about rebuilding our lives together, using the insights and energies this time has evoked.

It is structured as follows: in Part One, The Solitary Self, I look at the impact of the move from We to I on personal happiness and well-being, in terms of human loneliness, the overemphasis on self-help, the impact of social media, and the partial breakdown of the family.