M any institutions and individuals contributed assistance and advice in preparation of this book. Alex Barker (Milwaukee Public Museum), Thomas Emerson (University of IllinoisUrbana-Champaign), Robert Boszhardt (Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center), and John D. Richards (University of WisconsinMilwaukee) reviewed drafts and provided helpful comments and corrections. Diane Holliday of Tucson, Arizona provided copyediting services. Also contributing various forms of assistance were the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and Aztalan State Park, Susan Otto and the Milwaukee Public Museum, the Lake Mills-Aztalan Historical Society, Cahokia Mounds Historic Site, the University of WisconsinMilwaukee, Michigan State University, The Smithsonian Institution, Etowah Mounds Historic Site, University of Arkansas, Joan E. Freeman (retired, Wisconsin Historical Society Museum), Steve Stiegerwald of Lake Mills, Tom Davies (Aztalan State Park), Donald Gaff (Michigan State University), Jon Carroll (Michigan State University), and Woody Wallace (Earth Information Technology). A portion of the work described and included here was conducted with the support of National Science Foundation Grant #BCS 0004394 (Goldstein). Finally, we would like to thank the staffs of the Wisconsin Historical Society archives, library, museum, the Office of the State Archaeologist, and the WHS Press for providing innumerable services and resources.

Introduction

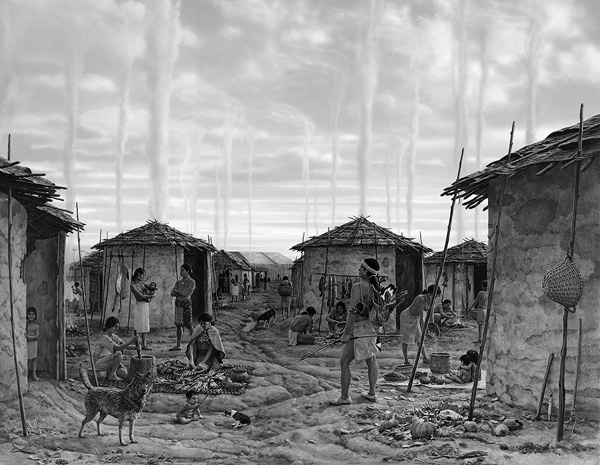

Figure A. Aztalan

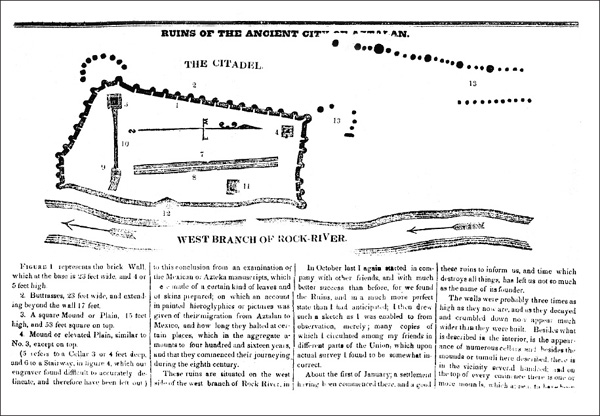

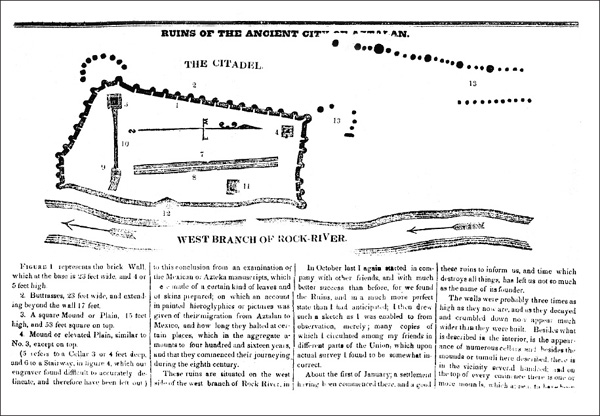

I n 1836, settlers to western Michigan Territory, now Wisconsin, made a discovery that would confound scholars and the public over the next century. Along the Crawfish River, fifty miles west of the new village of Milwaukee, the newcomers stumbled upon the burned ruins of a massive fortification enclosing flat-topped earthen mounds. These mounds appeared to be smaller versions of fine stone structures found in Mexico and Central America. It was dubbed the Citadel because it reminded settlers of an old fortress.

The discovery of the site, widely reported in newspapers of the day, posed a great mystery. Who built this fortress? American Indians of the region, recently removed by treaties, made no such structures. They had lived in small, modest villages. Further, no history had been developed for North America and the indigenous people left no records that could account for such places in the Midwest. Archaeology could not address the questions posed by the site since it would not develop as a formal discipline in the United States until the early twentieth century.

For these and other reasons, the settlers were reluctant to believe that native North Americans built these walls and mounds. Instead, the similarity of the site to the better known Aztec ruins in Mexico led to the conclusion that the Aztecs were involved and the site must be that of Aztalan or Aztln, the Aztec northern homeland. The name stuck to the site although today it speaks only of nineteenth-century attitudes and knowledge and says nothing about the inhabitants of this great town.

Figure B. First known map of Aztalan rendered by Nathaniel Hyer and published in the newspaper, Milwaukee Advertiser in 1837

As a result of archaeological work conducted throughout the twentieth century at Aztalan itself, archaeologists solved one mystery concerning the origin of the people who lived there. The large platform mounds and tens of thousands of artifacts found in the town link it to a remarkable civilization that archaeologists refer to as Mississippian. This civilization flourished between AD 1050 and the 1600s throughout the Mississippi River drainage, from Illinois to the Gulf Coast. The early capital of the Mississippian civilization was a large ceremonial, political, and urban center located near the Mississippi River in what is today, East St. Louis, in southern Illinois. In AD 1100, this exceptionally well-organized metropolis, complete with monumental architecture, supported a population variously estimated at 10,00015,000 people. Archaeologists named this Indian city, Cahokia, after a later tribe that lived in the area. The actual name of the city is lost forever, but surely it once was known far and wide and perhaps even feared and revered.

Just prior to AD 1100, a group of Mississippians from Cahokia, or some other place in Cahokias social sphere, migrated north to the Crawfish River in southern Wisconsin. Here they lived together with non-Mississippian groups, presumably friends, relatives, and allies. Together, these people lived at Aztalan for perhaps a century and a half. By AD 1250, the people had abandoned the town, foretelling the demise and eventual abandonment of Cahokia itself. By AD 1400, the Mississippian lifeway mysteriously disappeared from the Midwestern landscape, and the focus of the Mississippian civilization shifted to the southeastern United States.