David Sacks - The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus

Here you can read online David Sacks - The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Independent Institute, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus

- Author:

- Publisher:Independent Institute

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

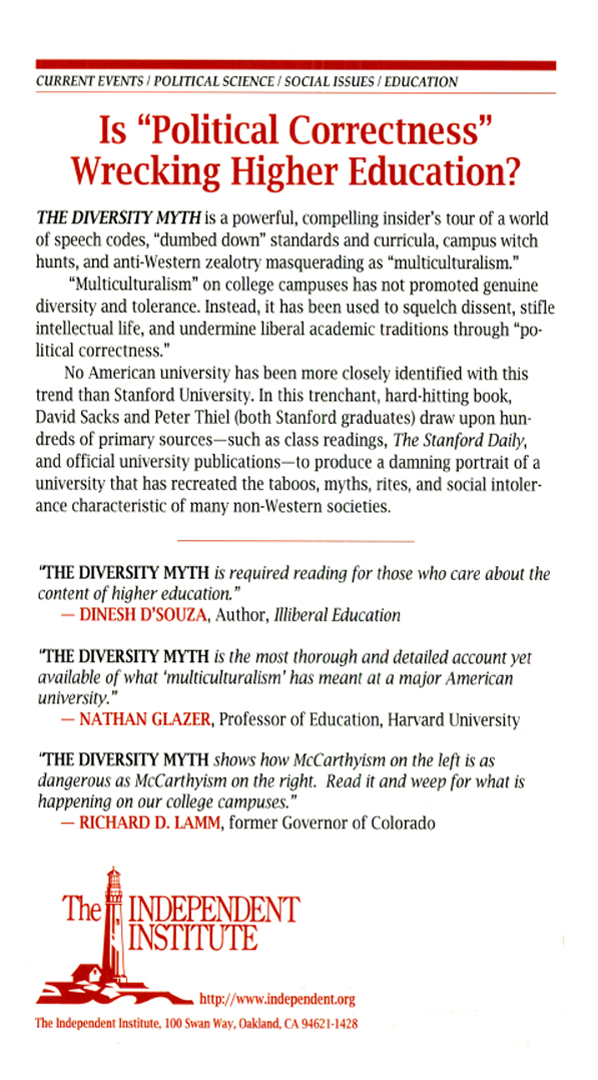

This is a powerful exploration of the debilitating impact that politically correct multiculturalism has had upon higher education and academic freedom in the United States. In the name of diversity, many leading academic and cultural institutions are working to silence dissent and stifle intellectual life. This book exposes the real impact of multiculturalism on the institution most closely identified with the politically correct decline of higher educationStanford University. Authored by two Stanford graduates, this book is a compelling insiders tour of a world of speech codes, dumbed-down admissions standards and curricula, campus witch hunts, and anti-Western zealotry that masquerades as legitimate scholarly inquiry. Sacks and Thiel use numerous primary sourcesthe Stanford Daily, class readings, official university publicationsto reveal a pattern of politicized classes, housing, budget priorities, and more. They trace the connections between...

David Sacks: author's other books

Who wrote The diversity myth: multiculturalism and the politics of intolerance on campus? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.