Diplomatic Games

DIPLOMATIC GAMES

SPORT, STATECRAFT, AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SINCE 1945

EDITED BY

HEATHER L. DICHTER AND ANDREW L. JOHNS

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic

reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear

as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged

to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Diplomatic games : sport, statecraft, and international relations since 1945 / edited by Heather L. Dichter and Andrew L. Johns.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4564-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-8131-4565-5 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4566-2 (epub)

1. Sports and state. 2. SportsInternational cooperation. 3. SportsPolitical aspects. 4. International relations. I. Dichter, Heather, author, editor of compilation. II. Johns, Andrew L., 1968- author, editor of compilation.

GV706.35.D57 2014

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

Contents

Andrew L. Johns

Heather L. Dichter

Evelyn Mertin

Jenifer Parks

Aviston D. Downes

Cesar R. Torres

Pascal Charitas

Antonio Sotomayor

John Soares

Kevin B. Witherspoon

Nicholas Evan Sarantakes

Wanda Ellen Wakefield

Fan Hong and Lu Zhouxiang

Scott Laderman

Thomas W. Zeiler

Introduction

Competing in the Global Arena: Sport and Foreign Relations since 1945

Andrew L. Johns

Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.

George Orwell, The Sporting Spirit

We see, therefore, that war is not merely an act of policy but a true political instrument, a continuation of political intercourse carried on with other means.

Carl von Clausewitz, On War

In late February 2013, former NBA star Dennis Rodman visited the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (DPRK) in what several media outlets characterized as a basketball diplomacy mission aimed at encouraging openness and better relations with the outside world. Rodman, whose antics both on and off the court overshadowed his prodigious skill as one of the best rebounders and defenders in NBA history, seems like an odd choice to be a diplomatic emissaryan unofficial one, to be sureof the United States to North Korea. His unique public persona aside, his visit occurred only weeks after the Pyongyang regime conducted its latest and most powerful nuclear test, which was strongly criticized by the United States, its allies, and other world powers for defying the United Nations ban against the North Korean nuclear program. Making the trip even more intriguing was the fact that the US Department of State had recently warned against a humanitarian visit by former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson and Google executive chairman Eric Schmidt. But as Aidan Foster-Carter, a Korea expert at Leeds University, told the Voice of America, Rodmans visit to the rogue state could potentially pay dividends: Were in a bad place with North Korea and the nuclear test and so on.... If someone tries something different, you know, outside the box, what harm can it do?

Rodmans surreal appearance courtside with the DPRKs supreme leader Kim Jong-Un is by no means the first time that sport and diplomacy have intersected. In the wake of World War I, Germany was excluded punitively from the 1920 Antwerp Olympics and the 1924 Paris Olympics. And the 1980 and 1984 Summer Olympics were marred by reciprocal boycotts by the United States and the Soviet Union (and their respective allies) in the midst of the tensions of the resurgent Cold War.

But the Olympic Games are only the most obvious moments of confluence. In the 1950s, sport played a key role in the Eisenhower administrations propaganda efforts to influence international opinion of the United States because they effortlessly stirred the interest of a wide audience.

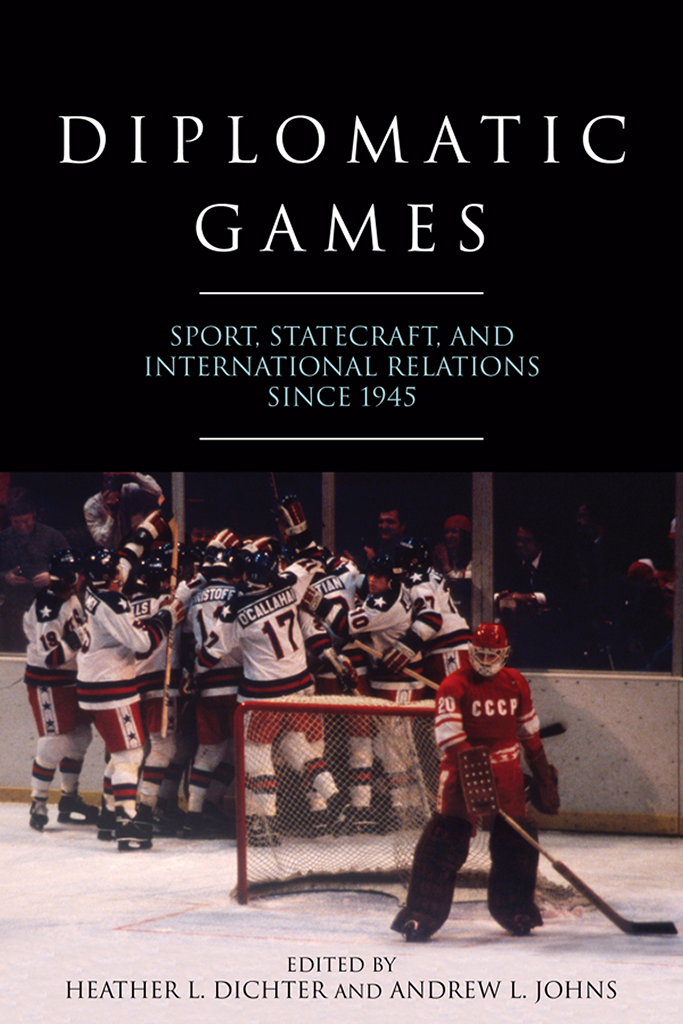

Why have two seemingly disconnected paradigms like sport and foreign relations overlapped so frequently? The answer is at once complicated and intuitive. Sport can, in the words of the legendary broadcaster Jim McKay, capture the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. This is true for individuals, teams, and even countriesconsider, for example, the national reaction in the United States to the disparate Olympic experiences of the US mens hockey team in 1980 and the US mens basketball team in 1972. Sport can be about twenty impoverished children playing soccer barefoot in the street or on a dilapidated field. It can be about pampered millionaire athletes playing in front of tens of thousands in stadiums with lavishly appointed luxury suites, not to mention millions of others watching on sixty-inch plasma screen televisions. Sport reflects common interests shared across borders and has the capacity to bring together groups otherwise divided by history, ethnicity, or politics. Sport can also transcend the playing field and influence society, culture, politics, and diplomacy. It can be a peaceful tool of goodwill or used as leverage to coerce behavior. It can exacerbate existing nationalistic tensions or be used to promote development and strengthen alliances. It can have a significant economic impact on a country or region, and it can be used as an effective weapon of propaganda. In short, sport is at once parochial and universal, unifying and dividing, and has the potential to fundamentally affect relations between individuals and nations.

As a result of its ability to cross political, cultural, social, gender, religious, and economic boundaries and provide a common foundation, sport is especially suitable as a vehicle to build bridges between governments and peoples. That helps to explain why high-profile athletes such as baseball Hall of Famer Cal Ripken, two-time Olympic medalist and five-time world champion figure skater Michelle Kwan, NBA stars Juwan Howard and Dikembe Mutombo, and WNBA all-star Nikki McCray were among those selected by US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice as American Public Diplomatic Envoys.