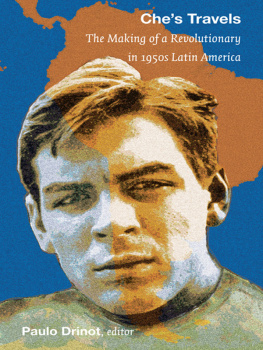

This book started to take shape at a workshop held at the University of Manchester in September 2006. I am especially grateful to all those who participated as discussants or panelists, and particularly to Patrick Barr-Melej, Maggie Bolton, John Gledhill, Penny Harvey, Alan Knight, Fernanda Pealoza, Patience Schell, and Peter Wade. Several institutions offered financial support that made the conference possible. I acknowledge gratefully the support of the research funds of the School of Arts, Histories and Cultures (SAHC), the School of Languages, Linguistics and Cultures, and the Centre for Latin American Cultural Studies (CLACS), all at the University of Manchester, as well as the Society for Latin American Studies and the Instituto Cervantes in Manchester. The Cartographic Unit at the University of Manchester helped with the production of the two maps of Ches travels. Special thanks go to Claudia Natteri, who, as CLACS administrator, was largely responsible for the logistics of the workshop, to the staff of the SAHC research office at the University of Manchester, and to Piotr Bienkowski and the staff of the Manchester Museum, where the meetings for the workshop took place. I am grateful to Valerie Millholland, Miriam Angress, and Neal McTighe of Duke University Press for their support in helping me bring this project to fruition. Special thanks go to the two anonymous reviewers chosen by the press. Their comments and suggestions have helped make this a better volume. Finally, in my capacity as the editor of the volume, I thank the contributors to this book for achieving a perfect balance of good humor and discipline throughout the publication process. I think Che would have approved.

Paulo Drinot

Introduction

For better or worse, justly or unjustly, Ernesto Che Guevara has come to represent the history of twentieth-century Latin America in a way that no other historical figure has done. There are good, objective reasons for this, not least his participation in the Cuban Revolution, arguably the single most important, and pivotal, process in twentieth-century Latin American history; a process that radically redefined Latin Americas role in the global political theatre. But there are also other, more subjective reasons, reasons that historians and social scientists would be foolish to ignore. Che, it must be said, was an attractive man. His allure derived partly from his good looks but equally, and perhaps primarily, from the fact that he appeared to lead the sort of life that many men, and some women, secretly or avowedly wished to lead themselves. Either because they, too, believed passionately in revolution as the means of achieving social justice or, more likely, because they associated the man with adventure and a break from convention, many in Latin America and throughout the world came to identify with Che, or the idea of Che. Irrespective of the ways in which the Cuban Revolution sought to claim Che as its primary symbol, in the half century that saw the rise of the global media, Che quickly became a global political phenomenon and a cultural artifact that seemed to condense both the very spirit of revolution (in both a social and an individual sense) and the history and culture of Latin America and the way that region came to be understood in a broader global context.

Ches enduring appeal was confirmed recently by the critical and box office success of Walter Salless film, The Motorcycle Diaries, released in 2004. Based on the diaries written by Guevara and his traveling companion, Alberto Granado, during their journey across South America in the early 1950s, the film revived general interest in Guevaras life and, particularly, in his prerevolutionary experience. Yet perhaps surprisingly scholarship has largely ignored not only this period in Guevaras life but also the entire crucial decade for Latin America. The present volume seeks to address this gap in the literature by exploring the Latin America that Guevara encountered on his travels across the continent prior to boarding the Granma in late November 1956 on his way to Cuba and, more important, to the revolutionary pantheon. The contributors to this volume explore how Guevaras Latin American travels produced Che and how Che simultaneously produced Latin America through his travelogues. They do so by using Guevaras travels and, particularly, his travel writings as a window both into the societies that he encountered at that particular historical juncture and into the impact that the experience of those societies had on him. But the contributors also consider how Latin America has reproduced Che by examining the various roles assigned to him and the claims made on him by various actors. The chapters in this book thus focus on three interconnected themes: (1) the societies that Che encountered and experienced during his travels across the continent in the early 1950s; (2) Ches representations of those societies in his travelogues and other writings; and (3) Ches broader legacy for the societies he experienced. Each contributor places different weight on each of these themes, reflecting both individual interests and the nature of the documentary material engaged (Che, as we will see, had a lot more to say about Guatemala or Peru than about Colombia or Venezuela).

As various contributors to this volume remark, in some ways the man of the period covered by his early travel writings was little more than a young, petulant, and not very insightful Argentine of no great historical interest other than that he was to turn from the moth of Ernesto Guevara into the butterfly of Che. Yet as a number of historians have shown, relatively unimportant or ordinary historical figures may prove to be extraordinary conduits through which to understand complex historical processes. There may certainly exist many more such diaries telling of the incredible regional mobility of Latin Americans in the middle decades of the twentieth century. But so far few if any historians have sought to uncover them, let alone make them centerpieces of historical study. Given Guevaras subsequent historical trajectory, a closer examination of his youthful experience that moves beyond the purely biographical seems eminently worthwhile.

By approaching Guevaras early travels as a conduit to historical study, the current volume provides a critical perspective and a fresh interpretative framework on a broad range of themes central to the history of Latin America and the regions global relations. In particular, the volume makes an original incursion into the recent and ongoing scholarly reassessment of Latin Americas experience of the Cold War. Various historians, political scientists, and literary theorists have sought to complicate our understanding of this key period by considering how the Cold War was not experienced merely at the level of high politics, international relations, or diplomacy but also as the politicization and internationalization of everyday life and familiar encounters. As the chapters in this volume illustrate, Guevara experienced the Cold War