Table of Contents

I Used to Know That

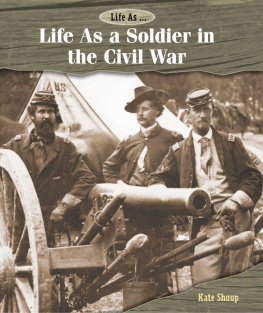

CIVIL WAR

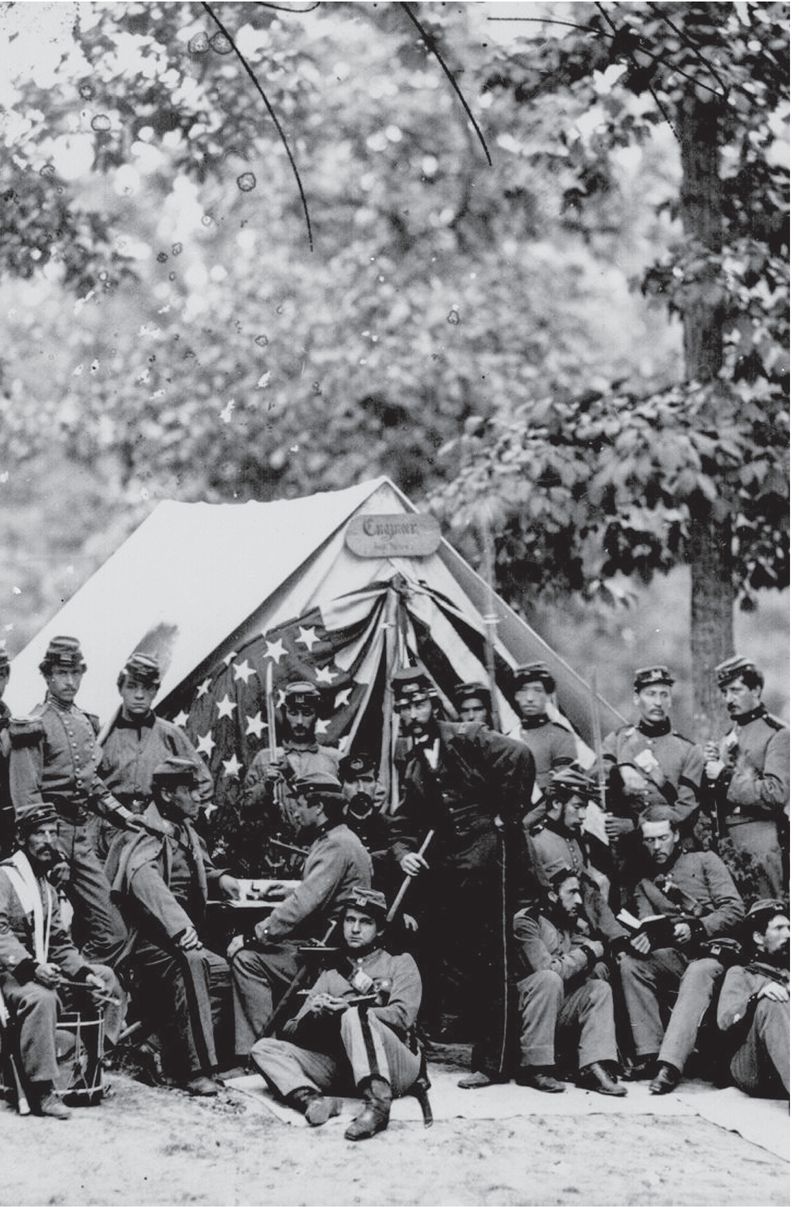

Engineers of the 8th N.Y. State Militia, 1861

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Richard Bailey, whose studious research and advice proved invaluable as this book took shape. The contributions of writers Martha Hailey, Bruce Kauffman, and David Diefendorf are also greatly appreciated. The librarians at the New York Public Library deserve a grateful nod as wellas do the following people, organizations, and institutions:

Curt Anders, Sarah Arnold, Jim Buie, Dr. Victoria E. Bynum, Nell Campbell, Scott Gampfer, Annette Haldeman, Hari Jones, Robert Keathley, Alfred Kennedy, Patricia Keats, Deb King, Phillip Mitchell, Patricia Murphy, Cassandra Reagor, Donna Schmidt, Mark Thomas, Jim Waecter, and Carl Westmoreland

African-American Civil War Museum, Alexandria (New Hampshire) Historical Society, Ball County (Virginia) Historical Society, Cincinnati History Museum, General Lew Wallace Study and Museum, Hildene Estate, Maryland Historical Society, Maryland Legislative Reference Library, Museum of the Soldier, National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, and the Society of California Pioneers

Introduction

THE ROAD TO WAR

Flirtation with secession is as old as the United States itself. New York anti-Federalists almost refused to ratify the Constitution. A handful of Federalist objectors to the War of 1812 argued for the secession of New England. South Carolina declared federal tariffs increasing the cost of imported goods null and void with an 1832 ordinance, then passed a law authorizing a state military forcea bold stand for states rights.

Despite such threats, our earliest statesmen could hardly have imagined a day when the sons of the North and South would battle to the death for four long years. How could such a conflict have come to pass?

Distant Worlds Rice, indigo, and cotton were the Souths cash crops from the colonial days on. Cotton production increased sevenfold between 1830 and 1850, and the slavery on which it relied became more and more entrenched.

At the same time, sectionalismexcessive devotion to regional intereststightened its grip. People of the sparsely industrialized South took pride in their suspicion of the federal government, the gentility of the planter class, the slow pace of life, and even their paternalism toward the 40 percent of the population in bondage.

As farmland became exhausted, planters aimed to move on to new territories and take slavery with them. Politically, slave power gave Southerners congressional influence beyond their numbers, and legislative compromises, which beginning with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, sought to maintain the balance of power between northern and southern states.

The North was an industrial powerhouse. Its vestiges of slavery disappeared in the 1820s, and increasing urbanization and diversity became the new normal above the Mason-Dixon Line. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men was a byword, but many Northerners feared the prospect of competing with freed blacks for jobs.

Whether slavery would die a natural death over time or spread throughout a nation poised to conquer the world was the burning question.

Politics and Religion Naturally, not all Southerners were proslavery, and not all Northerners were antislavery. But it was majority opinion that mattered. At mid-century, political parties were molded from factions of old ones, and the Republican Party emerged as the voice of those who wanted to halt the expanse of slavery to territories soon to be annexed as states. The Democratic Party would split over the issue.

Throwing morality and civil rights into the mix were social reforms born of the so-called Second Great Awakeningthe Protestant revivalist crusade that swept the nation in the early 1800s. Activists in the North and South alike launched temperance, womens suffrage, and abolition movements, and the abolitionists set off the noisiest alarms.

A Quadruple Whammy In the 1850s four key eventsthree legislative and one literaryinched the nation toward disunion.

Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850 This act was a payoff to the South for its support of the admission of California as a free (nonslave) state and the end of slave trading in Washington, D.C. The poison pill within was the Fugitive Slave Lawso grievous it tipped on-the-fence Northerners to the antislavery side and increased traffic on the Underground Railroad.

Publication ofUncle Toms Cabin

Publication ofUncle Toms Cabin Harriet Beecher Stowes 1852 novel depicting the human costs of slavery heightened antislavery sentiment in the North and outraged the slaveholding South.

KansasNebraska Act of 1854

KansasNebraska Act of 1854 This act stipulated that a vote by citizens of a territory would determine its free-state or slavestate status. Violence soon erupted in Kansas as free-staters and proslavery guerrillas fought over its fate.

Dred Scott Decision

Dred Scott Decision The Supreme Courts 1857 ruling in

Scott vs. Sandford not only declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional (stripping Congresss power to ban slavery in new territories) but also made it impossible for even free blacks with slave ancestry to become citizens.

The Split One blood-soaked fighter in Kansas was John Brown, who hatched a plot to start a slave rebellion and, in 1859, attacked the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. After Browns trial and execution, the national fever rose as adversaries celebrated his martyrdom or decried his wild-eyed fanaticism.

It wasnt Brown who ignited the spark that flamed into Civil War. It was the November 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln (not a die-hard abolitionist, but dead set against slaverys spread) and the subsequent secession of seven states.

Compromise of 1850 This act was a payoff to the South for its support of the admission of California as a free (nonslave) state and the end of slave trading in Washington, D.C. The poison pill within was the Fugitive Slave Lawso grievous it tipped on-the-fence Northerners to the antislavery side and increased traffic on the Underground Railroad.

Compromise of 1850 This act was a payoff to the South for its support of the admission of California as a free (nonslave) state and the end of slave trading in Washington, D.C. The poison pill within was the Fugitive Slave Lawso grievous it tipped on-the-fence Northerners to the antislavery side and increased traffic on the Underground Railroad. Publication ofUncle Toms Cabin Harriet Beecher Stowes 1852 novel depicting the human costs of slavery heightened antislavery sentiment in the North and outraged the slaveholding South.

Publication ofUncle Toms Cabin Harriet Beecher Stowes 1852 novel depicting the human costs of slavery heightened antislavery sentiment in the North and outraged the slaveholding South. KansasNebraska Act of 1854 This act stipulated that a vote by citizens of a territory would determine its free-state or slavestate status. Violence soon erupted in Kansas as free-staters and proslavery guerrillas fought over its fate.

KansasNebraska Act of 1854 This act stipulated that a vote by citizens of a territory would determine its free-state or slavestate status. Violence soon erupted in Kansas as free-staters and proslavery guerrillas fought over its fate. Dred Scott Decision The Supreme Courts 1857 ruling in Scott vs. Sandford not only declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional (stripping Congresss power to ban slavery in new territories) but also made it impossible for even free blacks with slave ancestry to become citizens.

Dred Scott Decision The Supreme Courts 1857 ruling in Scott vs. Sandford not only declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional (stripping Congresss power to ban slavery in new territories) but also made it impossible for even free blacks with slave ancestry to become citizens.