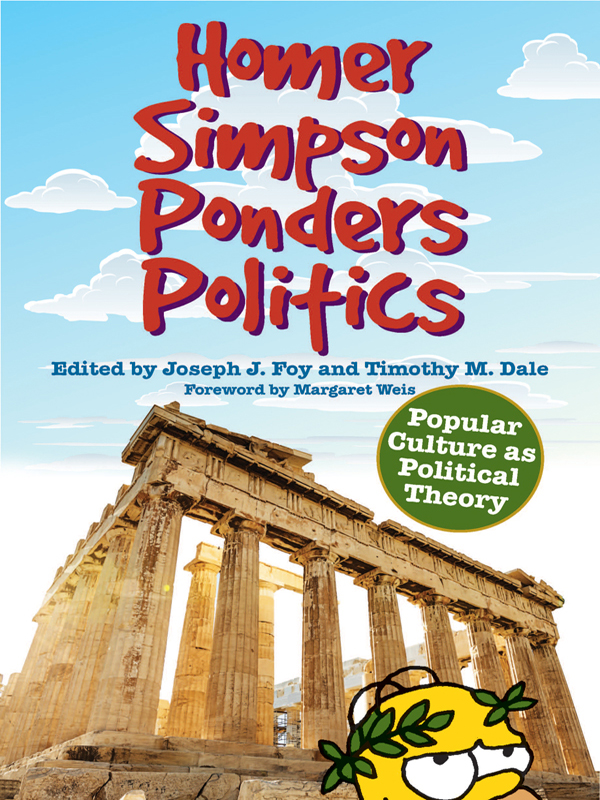

Homer Simpson Ponders Politics

HOMER SIMPSON

PONDERS POLITICS

Popular Culture as Political Theory

Edited by

JOSEPH J. FOY

TIMOTHY M. DALE

Foreword by

MARGARET WEIS

Copyright 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-8131-4147-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-8131-4150-3 (epub)

ISBN: 978-0-8131-4151-0 (pdf)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

This book is dedicated to our parents.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Popular Culture as Political Theory: Plato, Aristotle, and Homer 1

Joseph J. Foy

Dean A. Kowalski

Timothy M. Dale

Eric T. Kasper

Susanne E. Foster and James B. South

Matthew D. Mendham

S. Evan Kreider

Mark C. E. Peterson

C. Heike Schotten

Jamie Warner

Denise Du Vernay

Carl Bergetz

Mary M. Keys

Joseph J. Foy

FOREWORD

In describing what it means to be an author, Gary Paulsen once told me something I always remember: We are the guy in the tribe who puts on the wolfskin and dances around the fire.

That ancient storyteller was an entertainer. He made the members of his tribe forget that they were shivering with cold or wondering where they might find the next meal. But he was doing more than entertaining. Through his tales, the storyteller was passing on tribal traditions, maintaining an oral history of his people, and instilling values that would enable them to survive.

He used the thrilling story of an exciting hunt to show the members of the tribe working together to bring down game. His description of a warriors heroic death that ended up saving his people taught the value of self-sacrifice. The storyteller learned how to embellish the story in ways that stirred the emotions of those hearing it, so that they would remember it. If Homer had never told his tale, how many of us today would know about the fall of Troy?

As storytellers, we want our readers to enjoy our work, but we also want them to think about it. In fantasy fiction, the presence of different races such as elves and humans and dwarves gives the author the perfect opportunity to talk about racial discrimination. Not only is racial tension a good storytelling element; reading about the hurt and anguish and indignation suffered by an elf who is thrown out of the humans-only tavern can encourage readers to think about race relations in their own lives.

Since many adventurers often frequent taverns, my coauthor, Tracy Hickman, and I decided to make one of our characters an alcoholic. We did research on the subject and attempted to make our portrayal as accurate as possible. In writing about his struggles and the problems the other characters encounter trying to deal with him, we hoped to reach those readers who might find themselves in the same situation. We also wanted to encourage other readers to give serious thought to the issue.

Not only do human prejudices and fears, flaws and failings make for good storytelling; they serve to ground the fantastic in what the reader knows to be real, helping the reader suspend disbelief. One reason the Harry Potter novels are so successful is that they are about children in school. Never mind that in this school the children fly on broomsticks. The idea of being a kid in a classroom, having to deal with classmates and teachers, is something to which we all can relate.

Readers of books and those who write them will find much to think about in this interesting and entertaining book. I feel very privileged to have been invited to write the foreword.

And now, if youll excuse me, I have to go find my wolfskin. Its time to tell a story.

Margaret Weis

Introduction

POPULAR CULTURE AS POLITICAL THEORY

Plato, Aristotle, and Homer

Joseph J. Foy

When people told themselves their past with stories, explained their present with stories, foretold their future with stories; the best place by the fire was kept for the storyteller.

The Storyteller (opening sequence)

In 1987 Jim Henson, most famous, of course, for his Muppets, created and produced the first installment of The Storyteller. Combining live acting and puppetry, Henson used this award-winning television series to recreate myth narratives from around the world and, in the process, remind audiences of all ages of the importance and power of the stories a society chooses to tell. In each episode, the Storyteller (in the first season played by John Hurt and in the second season by Michael Gambon) magically brought to life tales of German, Russian, Celtic, Norwegian, and Greek traditions, each one offering humanistic insights into questions of power, ethics, religious belief, tradition, social hierarchy, the individual, and the other. These tales, which had been told throughout time and across cultures, served as a means for dealing with the big questions that have long plagued communities of people: questions about truth, justice, freedom, equality, and ethics. And underneath the stories lay expressions of cultural values and frameworks for understanding the world and our place within it.

Campbell and other mythologists and folklorists, who ultimately address the common themes and symbols found through a cross-cultural comparison, use the popular stories shared within societies to reveal deeper insights into the messages they convey about the common philosophies contained in those societies.

It will likely come as no surprise to students of political theory, then, that mythsshared through stories, music, poetry, art, and sermonhave always been a way to communicate the principles and ideals of a society, as well as to frame and present insights regarding liberty, property, justice, rights, power, and community. Philosophers dating back to Confucius (551479 BCE) praised poetic works like those contained in the Chinese Book of Songs (many of which were also, or later became, popular songs), noting that such poems are invaluable to moral education. Italian philosopher Machiavelli (14691527) turned to dramatization to present a philosophical allegory about virtue ethics and community: his play La Mandragola. More recently, Ayn Rand (19051982), a screenwriter-playwright turned novelist and philosopher, influenced countless conservative, libertarian, and Objectivist thinkers with her popular fiction novels

Next page