The Feminist Classics series brings together foundational texts in the critical and left feminist traditions, including works of politics, history, and critical thought. Addressing debates that continue into the present day, it aims to inform contemporary discussion about feminism at the intersection of class and race.

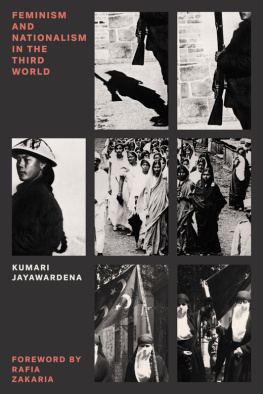

Feminism and Nationalism

in the Third World

Kumari Jayawardena

Cover photos: Chinese Lady Recruit, one of the many

women volunteers in the Southern Armies of Canton

China, 1922; Nationalists Demonstrating in Cairo, 1919

This edition published by Verso 2016

First published by Kali For Women 1986

Kumari Jayawardena 1986, 1992, 2016

Foreword Rafia Zakaria 2016

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-429-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-431-7 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-430-0 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

I am a new woman.

I seek, I strive each day to be that truly new woman I want to be.

In truth, that eternally new being is the sun.

I am the sun

The new woman today seeks neither beauty nor virtue.

She is simply

crying out for strength,

the strength to create this still unknown kingdom

Hiratsuka Raicho (1911) (Sievers 1983: 176)

To the memory of my mother, Eleanor (Hutton) de Zoysa,

and my aunt, Doris Hutton,

and for Doreen (Young) Wickremasinghe

The present de-colonial moment is not a hopeful one for feminist solidarity; the coming together of women from distant parts and portions of the world to claim in some unison the centrality of feminist identity seems an unlikely if not discarded project. The vagaries of power and privilege borne of colonialism have imposed disparate fates on the female; and as the dissection of these varied fortunes proceeds, the inequities unearthed, the injustices revealed have pushed dialogue into a realm rife with complication and recrimination. The replication of old colonial patterns in neo-imperial ventures such as the American foray into Afghanistan and Iraq, the former explicitly predicated on the liberation of Afghan women, have further muddied the waters. US feminist groups such Feminist Majority have championed these allocations, ignoring their inherent attachment to bombings and raids. All of it recalls colonial patterns; and all of it has led to misgivings and an ever-expanding chasm between female activists, and questions about the possibility of solidarity.

It is not simply the formerly colonized who come with misgivings. In the West, post-feminist scepticism has rendered the very label feminist irrelevant to some, and itchy, awkward and constricting to others. There have been arguments against the narrowness of the term feminist, against its capacity to include marginalized identities and to enable the intersections that such inclusion should garner. Resurrections of feminist discourse, to the extent they have occurred, have remained preoccupied largely if not exclusively with the concerns of the white, upper-middle-class woman, pushing tomes written around their careerist aspirations of Leaning In and Having it All to the tops of best-seller lists. Eagerly consumed and much discussed, they have moved feminist critique away from the state and instead to the individual female, her inability to speak up and model male aggression as at least partial reasons why gender inequality persists.

To modify Rousseaus famous (and exclusionary) words, woman is born free but is everywhere in chains.

It is this quagmire of separation and scepticism that makes Kumari Jayawardenas Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World a crucial text, the basis for answering questions that many believe have no answers. In tracing the history of early feminisms from India to Sri Lanka, Iran to Japan and several other countries, she provides a historical narrative that grounds feminist consciousness in indigenous histories, in the struggles of women whose names do not ordinarily appear in the nationalist stories that dominate most post-colonial societies. Even as she does this, she recognizes that such resurrections are themselves tainted by the sources from which they are constructed. The country studies in the volume, even while they refer mostly to historical periods prior to the advent of Western imperialism, rely inevitably on descriptions from foreign missionaries and travellers, or from local nationalists, male reformers and only finally from women who were active in feminist struggles. This problem of sources that Jayawardena correctly identifies has led to one of two approaches to the task of excavating early feminist history. The first discards all for its taint; the second, equally a response to imperialism, reifies indigenous practices, even misogynistic ones, as a revitalization of lost cultural authenticity.

It is possible to evade both of these pitfalls, and Jayawardenas work shows us how. Its relevance to two feminist audiences is the focus of the remainder of this essay.

The first are feminists in the West who seek to create more meaningful dialogue with feminists from the global south (the latter term having succeeded Third World in global discourse). This includes everyone aid workers, journalists, NGO staff, students and the ever growing cadres of Western female travellers who want their experience of the world, and particularly of feminist consciousness, to be deeper than the puerile support of war-projects that sell themselves as directed by the emancipation of this or that group of impoverished females.

The second are feminists of the global south who are faced with the tricky task of calling out misogyny in traditional and cultural practices under the omniscient shadow of an imperialism that has justified evisceration of all colonized culture as justified by the moral project of improvement and enlightenment. As a columnist for Dawn, the largest English newspaper in Pakistan, I routinely face these questions from feminists who are fighting on two fronts: against misogynistic cultural norms resurrected as emblems of cultural authenticity and a necessity for de-colonization, and against a resurrected imperialism that routinely latches on to womens issues to paint the non-white others as inherently backward, always requiring external assistance to realize equity or empowerment. It is these two groups that I wish to address, in turn, in this foreword.

To Western Feminists

Every year on International Womens Day and sometimes on one of the other days that commemorate and seek to draw attention to an internationalist feminist identity, there is an attempt to make the feminist conversation global. In line with this effort, women from prior colonies or new ones, Pakistan and Haiti, Afghanistan and Iraq, are gathered on a stage at one or another conference, often held in cities that were colonial metropoles or, in the case of New York and Washington D.C., are centres of neo-imperial internationalism, and given a few minutes to speak about the challenges they face. The conversation is hopeful but predictable; women from the global south, eager to participate in a global discourse from which they are usually excluded, say all the right things; it is what they are expected to do in these contexts, their presence often paid for by Western host organizations eager to put their inclusiveness on display. There are hugs and sometimes tears; awards are often handed out and the commitment to a feminism based on solidarity is deemed fulfilled: the formerly oppressed or currently bombed have been given a moment, a fully paid trip to the better world, a role as an emissary from the lesser world.