START A COMMUNITY FOOD GARDEN

The Essential Handbook

LAMANDA JOY

TIMBER PRESS

Portland + London

IM A BIG BELIEVER IN COMMUNITY GARDENS, BOTH BECAUSE OF THEIR BEAUTY AND FOR THEIR ACCESS TO PROVIDING FRESH FRUITS AND VEGETABLES TO SO MANY COMMUNITIES ACROSS THIS NATION AND THE WORLD.

FIRST LADY MICHELLE OBAMA

Remarks to U.S. Department of Agriculture, February 19, 2009

CONTENTS

PREFACE | Lot Lust, Rosie the Riveter, and Corporate Burnoutor Why I Became a Community Gardener |

Community activism, in the form of community gardening or any activity, wasnt something I had planned for my life. After studying musical theater in college I ended up, curiously, in the marketing world and, for almost twenty years, worked my way up from being a project manager in boutique marketing agencies to being an executive at a large event company. My teams within all these jobs were creativesdesigners, producers, directors. I loved how creative-team ingenuity could come up with incredible solutions to our clients marketing and communication dilemmas. But as I climbed the corporate ladder, traveled more, and had less time for my friends and family, I began to realize that something was missing. I longed for a greater connection with others and a more grounded lifestyle.

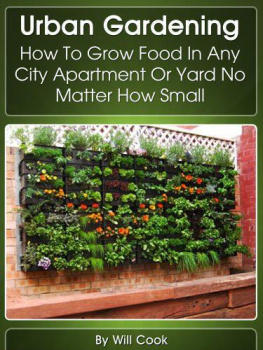

Food growing had always been my happy place. My father taught me to garden while I was growing up in rural Oregon. Many years later, as an urbanite in Chicago, I realized that this food-growing ability meant a lot to meas a way to have the best produce, but also as an escape from my increasingly challenging career. After seven springs, suffering miserably as a gardenless gardener living in a condo, my husband, Peter, woke up one late-winter morning and said, Should we go look for a house? Wait. Should we go look for a yard? And so we did, and we found our yard, with a house attached to it.

Our yarden, as I liked to call it, quickly transformed from 3,500 square feet of lawn and little else into an organic, heirloom garden paradise. I was so excited to be able to grow food again, I wanted to share my experiences and connect with other food gardeners in Chicago. So I started a blog called The Yarden to reach out to other like-minded people. Sadly, I found that there werent many who knew how to grow their own food. Lots of people were interestedeven desperateto learn this skill, but few were practitioners.

Around this time we were exploring our new neighborhood and my lot lust (when you see an empty lot and want to turn it into a garden) flared up. Living on the congested North Side of Chicago, there werent a lot of empty lots to lust after, so I fixated on one very close to my house at Peterson and Campbell Avenues.

A little relevant background: both of my parents were actively involved in World War II. My mother was a Rosie the Riveter and my father was with the Allied occupation forces in Japan. Like many people of their generation who had lived through both the Great Depression and World War II, my parents were very self-sufficient, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps kind of people. I was inspired by them, and much of that ethos rubbed off on me. However, the overdeveloped sense of responsibility I credit to (and sometimes blame on) my parents, was burning me out at work. I had become tired of using my talents to make money for companies whose values I didnt share. I was looking for a way to contribute in a meaningful way to my community. You could call it midlife crisis, I suppose. But instead of buying a very expensive car or getting a divorce, I started a community garden.

Back to that empty lot. While shopping at Muller Meats, our local butcher shop, I noticed a photo on the wall of a World War II victory garden. I asked the proprietors, Ruben and Irv, about the photo, and they explained that it was a large garden on Peterson Avenue during the war. I was familiar with the concept of victory gardenshow people on the home front had been forced to augment their families food needs. But seeing that photo, on that day, as a hungry gardener-transplantwell, I got very curious. In Oregon, many people know how to grow their own food; this agricultural know-how is part of the states heritage, and was still strong when I was growing up. I wondered if it was the same in Chicago in the 1940s. Did those city dwellers have a cultural history that predisposed them to know how to grow their own food during the war?

They say curiosity killed the cat. In my case, it was obsession that almost did me in. I became engrossed in the story of how Chicago fed itself during the Second World War. Much to my surprise, I learned that 90 percent of the people who grew food then in Chicago had never gardened before. They werent landscape gardeners who changed their tune and tried growing vegetables. They were flat-out garden rookies. And there were lots of them: Chicago led the nation in victory gardens during the war, with 1,500 community gardens and more than 250,000 home gardens. The largest victory garden in the United States was in Chicago.

The city was able to teach its citizens how to garden through a concerted educational effort, utilizing newspaper and radio, live demonstration gardens, classes, and an organized system of block captains, who were citywide garden leaders. This juggernaut of information and support created an atmosphere in which community gardens thrived, tens of thousands of home gardens sprouted up, and, some say, more than 50 percent of the produce consumed in the city during the war was homegrown.

Fast forward to 2010to me and my yarden, my if you dont like something, do something about it upbringing, that empty lot on Peterson and Campbell, and that photo on the butcher shop wallit all came together in one explosion of ideas and excitement on a spring day in 2010 as I drove by that empty lot once more, and realized it was the site of one of the victory gardens in the photo at the butcher shop.

I got an idea: What if I recreated a food garden almost 70 years later on that same spot? I could follow the model that was used during the warrevive the victory garden concept and teach people how to grow their own food. I talked with our alderman (a local government representative in Chicago) who got permission for the land from the owners, a local nonprofit. I started reaching out to neighbors and local businesses. I thought it would be great if twenty people wanted to garden together. As I was taking these fledgling steps with community leaders, nonprofits, and neighbors, little did I know that Peterson Garden Project would become the largest organic, edible garden in the city. Nor did I know that four years later it would encompass nine gardens, 4,000-plus gardeners and volunteers, a full-blown education program, and a home cooking schooland that it would completely alter the course of my life.

I tell you all this because you, too, may be ready to take the plunge into becoming a community garden leader. Your journey may not be as life-altering as mine was, but I promise that your experience with the community garden process will change youmost likely, for the better.

The idea for this book came about because Im asked a lot about how to start a community garden. Usually the focus is where to get the lumber or how to secure land, but, as youll learn while reading this book, a community garden is much more than the building materials. A community garden is an exercise in humanity, transformation, and joy.

It is my sincere wish that your community garden thrive, that you learn from the mistakes that I and other community garden leaders have madeand from the best practices those missteps have fostered. I also hope that your good work, wherever you are on this planet of ours, changes empty lots and empty lives into something remarkable: the beautiful place I like to call community.

Next page