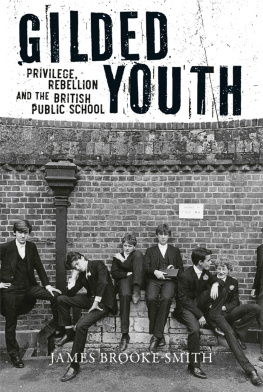

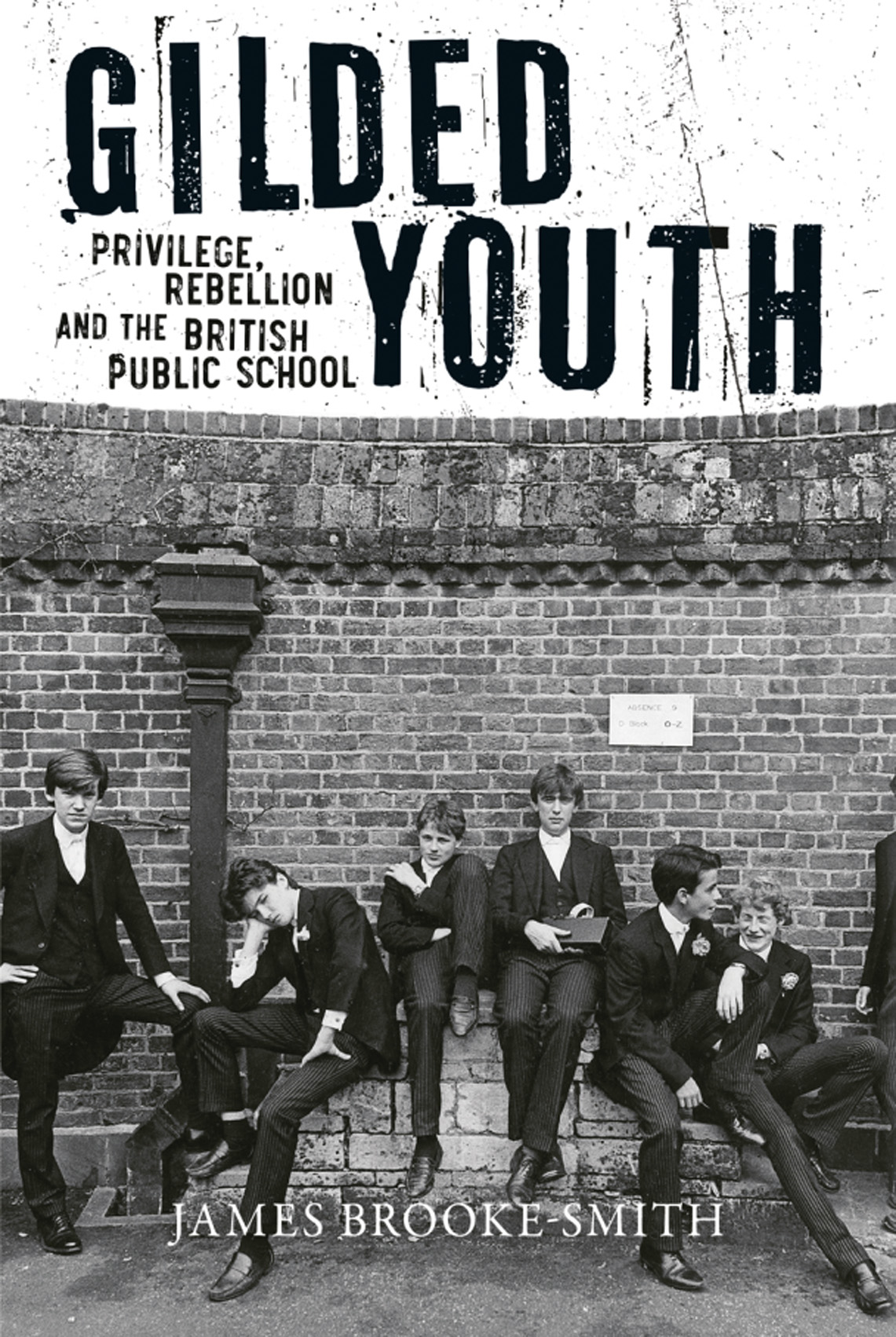

GILDED YOUTH

GILDED YOUTH

Privilege, Rebellion and the

British Public School

James Brooke-Smith

REAKTION BOOKS

For Leo and Freya

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London NI 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright James Brooke-Smith 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Prt. Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978 1 78914 092 7

Contents

Harrow School Bill, 2001.

Introduction:

Permanent Adolescence

N either the British jury, nor the House of Lords, nor the Church of England, nay, scarcely the monarchy itself, opined Leslie Stephen in 1873, seems to be so deeply enshrined in the bosoms of our countrymen as our public schools. Today few would echo Stephens belief in the mass popularity of public school education. Exclusive private schools are more often the subjects of heated debates about elitism and stalled social mobility than of misty-eyed veneration. But his comments nevertheless capture a perennial feature of the public school mystique, a set of associations that have clung to these institutions for most of their history, and continue to do so today. More than just an educational institution, the public school is a symbol of privilege and a shorthand for a particular vision of British national identity. With its elegant architecture and evergreen playing fields, it encodes a powerful myth of organic tradition and national heritage. As Stephen suggests, it is part of a network of ancient institutions that have proved remarkably skilful at adapting to historical change in order to maintain their position at the centre of national life.

The very first public schools were religious communities that contained grammar schools in order to instruct aspiring clerics in the Latin tongue and liturgy. Winchester College, founded in 1382, was housed in the diocesan grounds of Winchester Cathedral. Its original architecture was monastic: cloisters, chapel, chantry, vestry, wardens lodgings, brewhouse, gardens and a small schoolroom. Eton, the most elite of English schools, was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI concurrently with Kings College at Cambridge University. This act of institutional largesse was part of the Kings duties as Fidei Defensor, defender of the faith and steward of the Church in England.

Almost all of the early foundations, including those of the nine great schools Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster, Charterhouse, Rugby, Shrewsbury, Merchant Taylors and St Pauls made provisions for the education of the poor. William of Wykeham, founder of Winchester, stipulated that the school should provide board and tuition for seventy pauperes et indigentes as well as fee-paying pupils. Etons founding charter set aside funds and still does to this day for seventy collegers, who would be educated for free alongside the wealthier oppidans. In reality, this meant that the schools catered principally for the sons of tradesmen, merchants, professionals and the rural gentry. Classical education was of little practical use to the labouring poor, and many of the sons of the aristocracy continued to be educated by private tutors in the great houses until well into the eighteenth century. In the early 1700s the register of pupils at Eton included the sons of a baker, bookseller, brick maker, cheesemonger, grocer, innkeeper, tobacconist, mercer and coach maker.

But the schools original charters were gradually circumvented through long years of corruption, inertia and the influence of prosperous families who sought the benefits of public schooling without the coarsening presence of scholarship boys from the lower classes. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the schools were transformed into the elite establishments that they remain to this day. On the recommendation of the Clarendon Report of 1864, the first serious attempt by government to regulate the public schools, many of the original charters were amended to offer up scholarships to general competition, rather than leaving them in the gift of individual administrators or boards of governors. But this merely served to consolidate the grip of the already wealthy, as it ensured that only the sons of families who could afford expensive tuition had any chance of winning prizes. The process of class cleansing had reached its apogee by the 1920s, when George Orwell, who famously classified himself as lower upper middle-class, described his time at Eton as five years in a lukewarm bath of snobbery.

This tangled history is why the modern independent sector, as politicians and publicists like to call it, is still known to most people as the public schools. In reality, this term encompasses a huge variety of institutions that exist outside the state system, from the nine great schools, to former direct grant grammar schools, private schools owned by individuals or corporations, and a host of institutions that cater to particular constituencies and needs. It was not until the nineteenth century that the state considered mass education to be part of its remit at all. The first government-run schools were known as board schools, due to the fact that they were administered by local education boards, and are now part of the state sector. The schools founded in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were entitled to be called public in that they were charitable trusts, administered by boards of governors for the education of those who might not otherwise be able to afford private tutors. In the 1960s, under pressure from a Labour Party whose official policy was to nationalize all schools, the PR consultants hired by the Headmasters and Headmistresses Conference, the national organizing body for the public schools, successfully introduced the new term independent schools. This was a calculated makeover designed to deflect attention from the glaring contradiction between the way in which these institutions functioned to entrench the privilege of the wealthy few and their original purposes as charitable trusts for the deserving poor.

And function they still do. In September 2014 the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission, an advisory body to the Department of Education, found that 71 per cent of senior judges, 62 per cent of senior officers in the armed forces, 55 per cent of parliamentary secretaries in Whitehall and 53 per cent of senior diplomats were educated at private schools. Similar figures applied throughout the upper echelons of British society: 44 per cent of people on the Sunday Times Rich List, 43 per cent of newspaper columnists, 36 per cent of cabinet ministers, 26 per cent of BBC executives and 22 per cent of shadow cabinet ministers. All of this in a country where a mere 7 per cent of children enjoy a private education. The standout phrase from what was otherwise a bland and bureaucratic report was the assertion that Britain suffers from a closed shop at the top,