Rethinking the Western Tradition

The volumes in this series seek to address the present debate over the Western tradition by reprinting key works of that tradition along with essays that evaluate each text from different perspectives.

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE FOR

Rethinking the Western Tradition

David Bromwich

Yale University

Gerald Graff

University of Illinois at Chicago

Gary Saul Morson

Northwestern University

Ian Shapiro

Yale University

Steven B. Smith

Yale University

Selected Writings of Thomas Paine

Edited by

Ian Shapiro and Jane E. Calvert

with an Introduction by

Ian Shapiro

with essays by

J. C. D. Clark

Jane E. Calvert

Eileen Hunt Botting

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven and London

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund. Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2014 by Ian Shapiro and Jane E. Calvert.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Times Roman and Perpetua types by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Paine, Thomas, 17371809.

[Works. Selections. 2014]

Selected writings of Thomas Paine / edited by Ian Shapiro and Jane E. Calvert ; with an introduction by Ian Shapiro ; with essays by J. C. D. Clark, Jane E. Calvert, Eileen Hunt Botting.

pages cm. (Rethinking the western tradition)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-16745-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Political scienceEarly works to 1800. I. Shapiro, Ian, editor. II. Calvert, Jane E., 1970 editor. III. Title.

JC177.A5 2014

320.51'2092dc23

2014005794

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contributors

Eileen Hunt Botting is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame.

Jane E. Calvert is Associate Professor of History at the University of Kentucky.

J. C. D. Clark is an historian of Britain and America in the long eighteenth century.

Ian Shapiro is Sterling Professor of Political Science and Henry R. Luce Director of the MacMillan Center at Yale University.

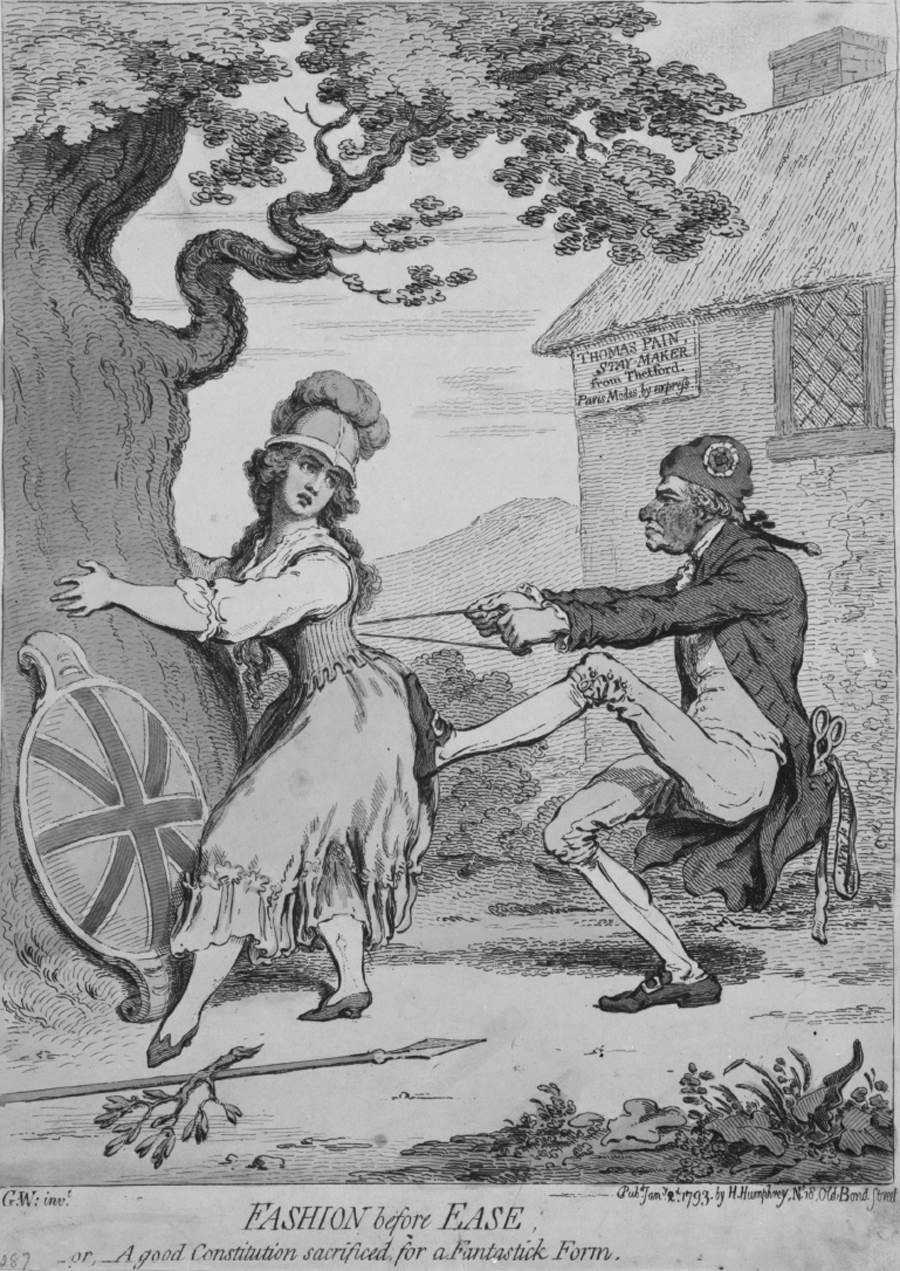

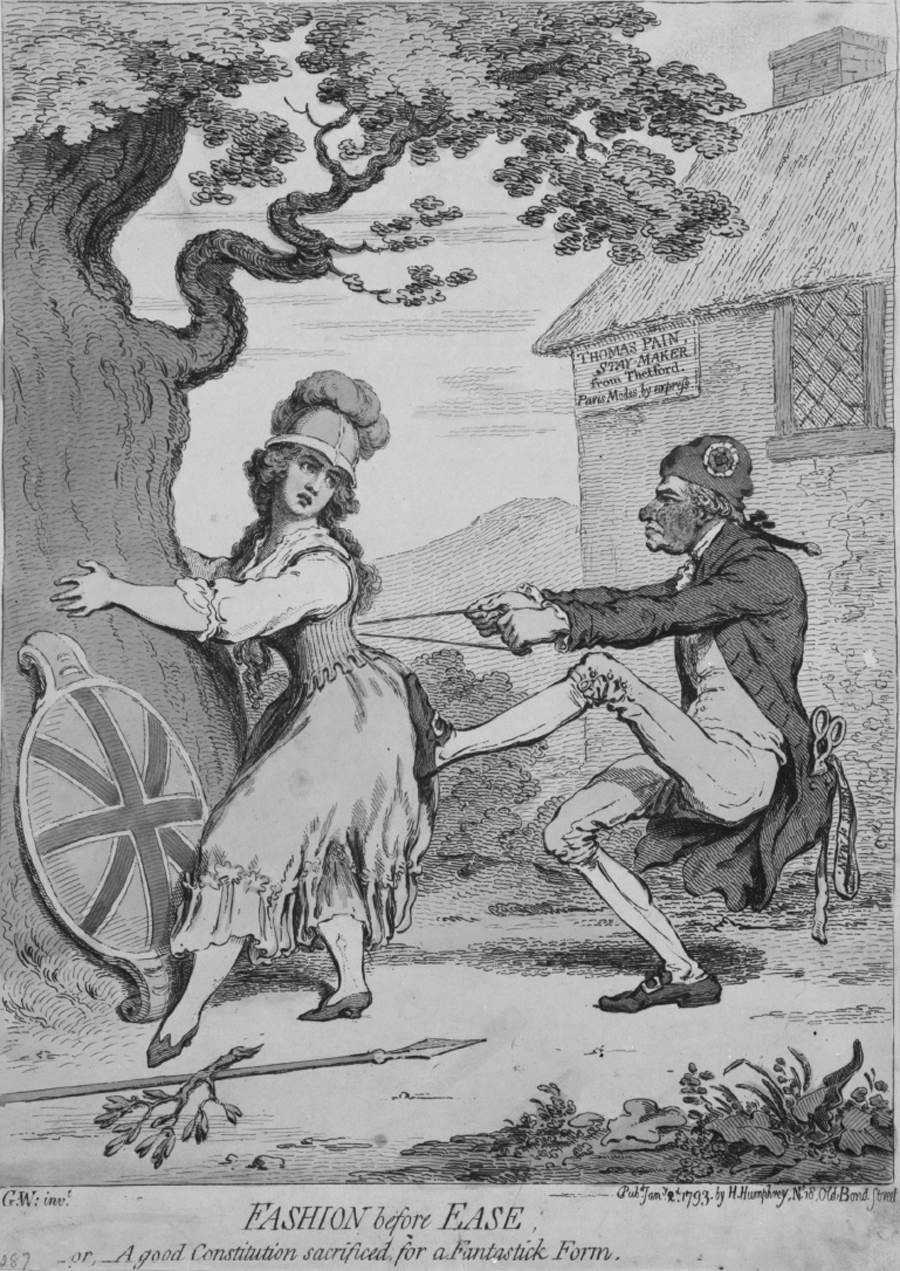

A 1793 cartoon by James Gillray showing Thomas Paine tightening Britannias corset. The tape protruding from his pocket is inscribed Rights of Man, and the cottage behind them is inscribed Thomas Pain, Staymaker from Thetford. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Acknowledgments

The editors would like to thank David Armitage, R. B. Bernstein, and Rogers Smith, as well as two anonymous readers for Yale University Press for their helpful comments and suggestions on the selections from Paines writings, the introduction, and the interpretive essays. Gaye Ilhan Demiryol also deserves thanks for her diligent proofreading of the transcribed documents.

Introduction

Thomas Paine, Americas First Public Intellectual

IAN SHAPIRO

Thomas Paine died in 1809 at the age of seventy-two, by coincidence the year in which both Charles Darwin and Abraham Lincoln were born. Lincoln would turn out to be a great Paine admirer.

Paine would have been incapable of heeding perhaps even of hearing such advice. Whatever he was, Thomas Paine was not circumspect. Convinced that life is a daring adventure, or nothing,

Yet Paine bounced back from his many catastrophes, sometimes with astonishing panache. Indeed, inventiveness and resilience marked him from the beginning. He would never have amounted to anything more than a regional excise collector in Lewes, East Sussex, England, were it not for his audacious self-confidence leavened by a capacity for bootstrapping, which has seldom, if ever, been matched. For all practical purposes self-educated and lacking any advantages of birth, Paine would become a major figure in elite circles in Britain, France, and the United States and a confidant of three American presidents as well as Napoleon Bonaparte. His mother was the daughter of a relatively well-to-do lawyer, but she married down, with the result that Paine had to leave school at the age of twelve and apprentice in his fathers trade of stay-making.

In 1756 the Seven Years War gave him his ticket out. Rejecting his fathers counsel, he enlisted as a privateer and earned a thirty-pound commission. This small fortune enabled Paine to move to London and talk his way into the bustling world of intellectual clubs and cafs spawned by the new intelligentsia, where he came to know among others Benjamin Franklin. This would turn out to be a fortuitous connection. In late 1774, following the death of his wife and child, his failed stay-making business and second marriage, and his dismissal from the excise service prompted by a quixotic attempt to get Parliament to improve conditions for tax collectors, Paine

Even armed with Franklins letter, which recommended Paine only for a modest teaching or clerical position, he faced an uphill battle in the New World. No one could have guessed then that this underachieving middle-aged misfit was soon to become a household name; that Common Sense (1776) and his sixteen pamphlets on The Crisis When the shivering, delirious Paine was carried off the deck of the London Packet in Philadelphias harbor in December of 1774, that all lay in the future.

Soon after Paine had recovered from the rigors of his transatlantic voyage, he persuaded one Robert Aitken, the owner of a bookstore and printing press, to start publishing The Pennsylvania Magazine under Paines editorship. It was an overnight success, in a few months attracting fifteen hundred paid subscribers. This made it the most widely read periodical in the New World. Paine wrote much of the magazine himself under various pseu donyms, honing the skills that would soon make him the best-selling author of his generation. He fell out with Aitken, however, while trying to renegotiate the terms of his employment, reflecting a dynamic that would repeat itself throughout his life: Paine fought not only with his adversaries but also with allies and even friends. Combining unusually large doses of generosity, courage, and vanity, he frustrated his supporters, goaded his enemies, and took enormous risks sometimes without seeming even to be aware of them. Among the reasons why Paine is a figure of enduring fascination is that he defies easy classification as a thinker or as a human being.

Paine was, first and always, an intellectual. Today he would be called a public intellectual. Among other things, this means that he was no politician.

Influence is one thing; politics, another. Paine wielded one of the most inspiring pens of the century, but this was not matched by a facility for persuasive public speaking. Few letters or other direct sources of evidence about his character have survived, yet it seems clear that, despite an arresting twinkle in his eyes, he was devoid of personal charisma. He could be engaging in conversation but was often withdrawn in company. Though tall and reputedly handsome, he had a bulbous nose that deteriorated with age, possibly due to chronic rosacea. This helped his enemies exaggerate his drinking, denigrating him as an alcoholic.Reason, meant that even the like-minded would often sidestep association with him.

Next page