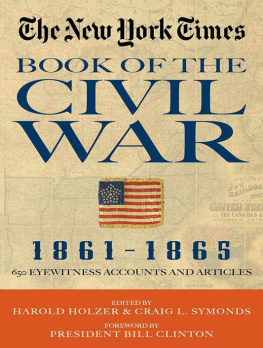

BOOK OF THE

CIVIL WAR

1861 1865

650 Eyewitness Accounts and Articles

EDITED BY

HAROLD HOLZER & CRAIG L. SYMONDS

FOREWORD BY

PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON

Copyright 2010 The New York Times

All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or illustration, may be used or reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher.

Published by

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

151 West 19th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by

Workman Publishing Company

225 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

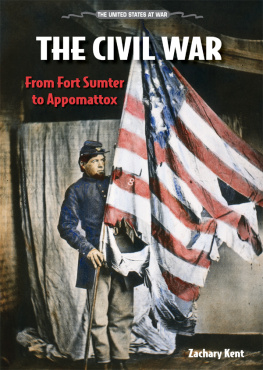

Cover design by Sheila Hart Design, Inc.

Cover art: 35 Star West Virginia Statehood Flag, Courtesy Jeff R. Bridgman American Antiques (www.jeffbridgman.com); Coltons new railroad and county map of the United States, 1862, Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Memory Project.

Photo Credits:

All images are courtesy of the Library of Congress, except for the following:

Pages , Harpers Weekly.

eISBN: 978-1-60376-376-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

18501860

MayNovember 1860

December 1860March 1861

AprilMay 1861

JuneJuly 1861

AugustOctober 1861

November 1861January 1862

FebruaryMarch 1862

AprilMay 1862

JuneJuly 1862

AugustOctober 1862

November 1862January 1863

FebruaryApril 1863

MayJune 1863

July 1863

AugustSeptember 1863

OctoberNovember 1863

December 1863February 1864

MarchApril 1864

May 1864

JuneJuly 1864

AugustSeptember 1864

OctoberDecember 1864

JanuaryFebruary 1865

MarchApril 1865

AprilMay 1865

18651877

Foreword

BY PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON

This is a book about a war and a newspaper: the Civil War the bloodiest and most transformative conflict in our history, and The New York Times, which recorded the events of the war and explained them to its vast audience.

In our own age of relentless information and opinion overload from 24-hour television news, talk radio, blogs, Facebook, Twitter, and the World Wide Web, the old-fashioned broadsheet newspaper with its narrow columns and tiny type may seem to be nothing more than a curious antique of limited reach. But such papers managed to elect presidents, propel (or depress) the national economy, sustain wars, and inspire the expansion of human freedom.

During the Civil War era, New Yorks daily newspapers gave an increasingly diverse population of local readers native-born New Yorkers, German and Irish immigrants, free African-Americans, and many others a vivid window into current events and forceful opinions on the most important issues. Their power to inform and persuade also reached well beyond their hometown base, through national editions that reached hundreds of thousands of people from coast to coast, an enormous audience for the period.

This golden age of newspapers did not necessarily guarantee readers greater reliability than the noisy outlets we have today. Unlike todays big urban dailies, nineteenth century papers did not pretend to be neutral and impartial dispensers of information. They were openly and proudly partisan. The New York Herald was the conservative-leaning Democratic paper; The New York Tribune was the paper of the liberal Republicans; and The New York Times was the paper of the establishment Republicans. (Of course, there has been some realignment in the positions of the major parties since Lincolns time!)

This book vividly reminds us just how strongly the Republican newspapers supported the Union during the Civil War, while the northern Democratic papers questioned and attacked the policies and practices of Lincoln and his administration and those published in the South supported the rebellion and the Confederacy. They were, in effect, the Fox News and MSNBC of their day. The Times, which in modern times has been called the Gray Lady, was anything but back then.

Even then, however, as this collection shows, The Times pioneered a somewhat different, subtler brand of journalism. Though the paper was unabashedly pro-Republican its founder, Henry Raymond, had served as the Republican speaker of the State Assembly The Times promised from the outset of the war to seek truth, avoid extremism, and strive for consensus. At a time when newspapers routinely used the kind of inflammatory language we currently associate with talk radio, this flagship of American dailies all but invented the policy of offering straightforward, temperate, and credible reporting.

Still, its efforts at restraint shouldnt be overstated. Readers who sample this collection edited by historians Craig Symonds and my friend Harold Holzer will see that its viewpoint was pro-Union and pro-Lincoln. The Times earnestly supported the war to suppress the Rebellion and, later, cheered the Emancipation Proclamation and the recruitment of African-American soldiers to fight for their own freedom. It condemned weak-kneed Unionism and urged loyalty to the Lincoln administration. Moreover, from the ardor and the emphasis on specific issues evident in the articles, it becomes clear that The Times did more than cheer from the sidelines: it helped spur a sometimes weary North to maintain the struggle to restore the Union and provide the new birth of freedom that Abraham Lincoln spoke of so eloquently at Gettysburg. Because there was no live coverage of momentous events, newspapers like The Times gave Americans their only record of the words Lincoln spoke that day. In doing so, it helped create what today we call the first draft of history.

Presidents of that era held no news conferences or daily briefings. Nor did they employ press and public relations specialists to defend their programs and hone their messages. Instead, they relied on friendly newspapers to print their letters and public statements. Abraham Lincoln made great use of this method of communicating with the American people, thanks in no small measure to The Times.

Times editor Henry Raymond continued running his newspaper even after he assumed the role of chairman of the Republican National Committee and began raising funds for Abraham Lincolns re-election campaign. There is no modern example of this kind of open political participation by journalists. Imagine the outcry today if the head of one of the major television networks assumed chair-manship of one of the major parties. During the era of the Civil War, such partisanship was not only tolerated, but accepted. Today independent groups issue reports on positive or negative bias in the coverage of candidates and officeholders, while media outlets routinely deny that it exists. Readers of this collection will decide for themselves how effective, responsible, and appropriate the system was then, and whether todays coverage would serve the public better if more media declared their sympathies openly.

For most Americans of the Civil War era, newspapers were the sole source of information social or political for a news-hungry population. They were there every morning for a penny or two. Often brilliantly written, they brought the Civil War with all its terror, grandeur, cruelty, suffering, triumph, and social change into American homes. They were the eyes and the ears of the people.