I BELIEVE THIS GOVERNMENT CANNOT ENDURE PERMANENTLY, HALF SLAVE AND HALF FREE.

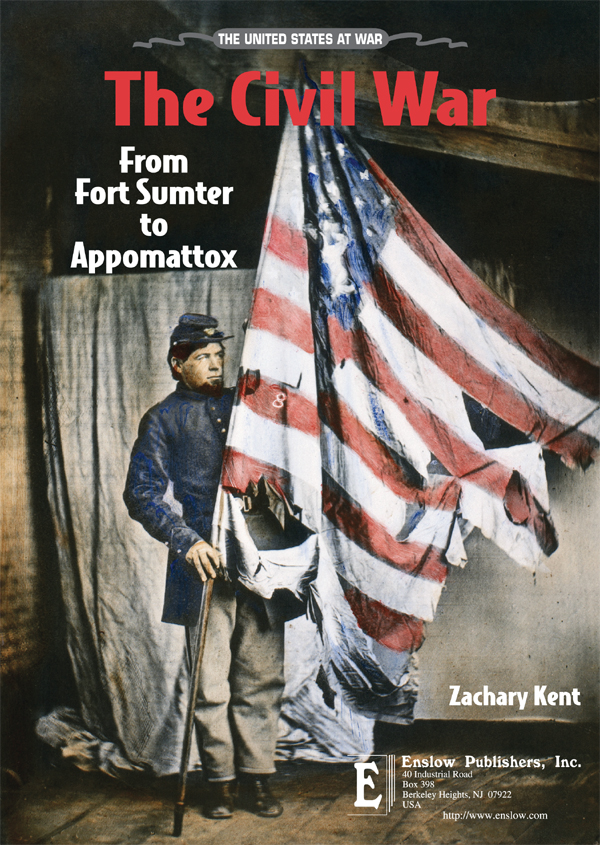

Abraham Lincoln delivered these prophetic words in a speech given only a few years before the Civil War erupted in the United States. The bloodiest conflict in American history forced neighbor to fight neighbor and brother to fight brother. More Americans lost their lives in this conflict than in any other war. From the hallowed battlefield at Gettysburg to the surrender at Appomattox, author Zachary Kent explores this pivotal time in American history, when a nation on the brink of destruction was reunited and permanently rid of slavery.

About the Author

Zachary Kent has published many books of history and biography for young people, including Dolley Madison: The Enemy Cannot Frighten a Free People for Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Image Credit: Library of Congress

The photograph of an old man hangs on a living-room wall in my fathers house. The man is George W. March, my great-great-grandfather. His hair is white and neatly combed. He has a long white beard, and his blue eyes shine with pride. Pinned on the front of his coat is the star-shaped medal awarded to Union veterans of the American Civil War.

As a boy, I listened to the stories my grandmother told me about Grandpa March. He fought with a Pennsylvania cavalry regiment and had horses shot from under him in battle. As a grown-up, I have visited many of the great battlefields. At Farmville, Virginia, I walked along the road where Grandpa March was captured during a cavalry charge on April 7, 1865. The Civil War is very real to me because it is part of my family heritage.

I believe no war ever touched as many American lives as did the Civil War. Between 1861 and 1865, the Northern states and the Southern states clashed in a struggle to decide the future of the nation. Americas husbands, sons, and fathers marched off to war. Some 3 million men would serve in the Union and Confederate armies. And after the last shot was fired, more than 600,000 soldiers lay in graves. The Civil War claimed more American livesfrom battle and diseasethan World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War combined. Entire cities were burned to the ground. The boom of cannons and the crack of rifle fire turned peaceful woods and farmlands into landscapes of blood and horror. Even today, the evidence of the Civil War remains on scarred battlefields, in vivid photographs, and in the memories passed down from generation to generation.

1

STORM OVER FORT SUMTER

I DID NOT KNOW THAT ONE COULD LIVE SUCH DAYS OF EXCITEMENT. EVERYBODY TELLS YOU HALF OF SOMETHING, AND THEN RUSHES OFF TO TELL SOMETHING ELSE, OR TO HEAR THE NEWS.

Charleston citizen Mary Boykin Chesnut, April 13, 1861

Fort Sumter! Newspaper headlines blared the name, and most Americans spoke of Fort Sumter in the spring of 1861. Along the waterfront of Charleston, South Carolina, angry citizens shook their fists out toward the sea. On an island at the mouth of the harbor three miles away, Fort Sumter stood proud and alone. Above its high brick walls, the red, white, and blue of the U.S. flag snapped boldly in the breeze.

America tottered on the brink of civil war. Already South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas had quit the Union. Together they formed the new Confederate States of America. Across the South, Confederate soldiers were seizing federal arsenals, forts, and navy dockyards.

Image Credit: National Archives

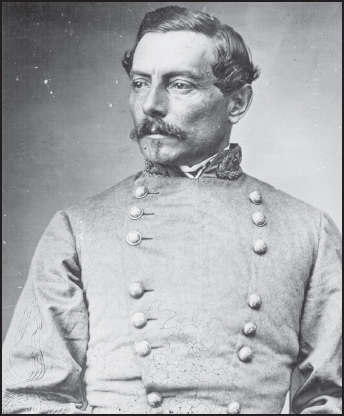

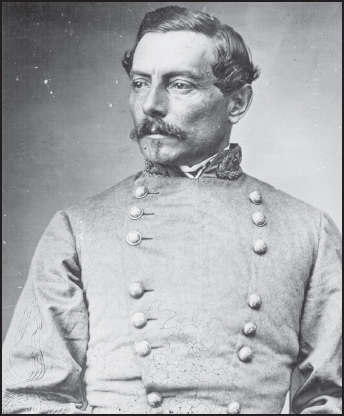

P. G. T. Beauregard commanded the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter.

In Charleston, tensions mounted day after day. For weeks, Southern militiamen arrived by train. Excitedly, these soldiers marched through the streets and pitched their tents outside the city. The Confederates demanded Fort Sumter. The U.S. government refused to give it up. Strike a blow! Southern politician Roger Pryor urged one cheering Charleston crowd. Gray-haired Major Robert Anderson commanded the small Union garrison at Fort Sumter. Nine officers, eight army musicians, sixty-eight enlisted soldiers, and forty-three civilian workmen (carpenters and bricklayers making repairs at the fort), a total of 128 men, obeyed Andersons orders.

Along the shoreline surrounding Fort Sumter, six thousand Confederate soldiers occupied Fort Moultrie, Fort Johnson, and other military positions. Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard of Louisiana commanded this Southern force. Beauregard knew Major Anderson well. More than twenty years earlier, as a West Point army cadet, Beauregard had learned his gunnery skills in an artillery class taught by Anderson. Now dozens of Confederate cannons pointed toward Fort Sumter. Gazing through binoculars, Major Anderson understood the growing danger. The clouds are threatening, he grimly wrote, and the storm may break at any moment.

In the early morning blackness of April 12, 1861, three Confederate officers on General Beauregards staff rowed a boat across the murky waters of the harbor. Stepping ashore at Fort Sumter, they demanded the surrender of the Union garrison. Major Anderson refused. One of the Confederate officers scribbled a note and presented it to Anderson. By authority of Brigadier General Beauregard it read, we have the honor to notify you that he will open fire on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time. The Southern officers rowed back to shore, and Major Anderson tensely waited. The moment of terrible confrontation had arrived.

At 4:30 A.M. , Confederate lieutenant Henry S. Farley jerked the lanyard of a cannon at Fort Johnson on James Island. A signal shell was sent soaring through the sky with a roar. One hundred feet above Fort Sumter, the shell burst in an explosion of flame. Many people had expected a fight. Still, the sudden noise startled Charleston citizen Mary Chesnut. I sprang out of bed, she later exclaimed, and on my knees I prayed as I have never prayed before. Confederate captain Stephen Lee recalled that the first shot brought every soldier in the harbor to his feet, and every man, woman, and child in the City of Charleston from their beds.

Over the next hours, the bombardment became deafening as every Confederate cannon joined in. The constant firing lit up the harbor sky. Union sergeant James Chester observed, Shot and shell went screaming over Sumter as if an army of devils were swooping around it. Not until 7:00 A.M. did the Union soldiers respond to the attack. Then the officer on duty, Captain Abner Doubleday, ordered Sumters guns to return fire. It was too dangerous to work the heavy Union cannons exposed on the open upper level of the fort. Within the forts sheltered lower level, however, twenty-one cannons stood ready for action. Our firing now became regular, Captain Doubleday later recalled, and was answered from the rebel guns which encircled us.

Cannonballs and artillery shells poured into the fort. Smashed bricks went flying, and mortar dust clouded the air. Great shells buried themselves into the parade ground, making the earth shake. The fort suffered, declared Sergeant Chester, a perfect hurricane of shot. In Charleston, many citizens watched the thrilling spectacle from their rooftops. They jammed the wharves for a good view and crowded onto the beaches. Boom, boom, goes the cannon all the time, exclaimed Mary Chesnut. The nervous strain is awful.