Raising the White Flag

CIVIL WAR AMERICA

Peter S. Carmichael, Caroline E. Janney, and Aaron Sheehan-Dean, editors

This landmark series interprets broadly the history and culture of the Civil War era through the long nineteenth century and beyond. Drawing on diverse approaches and methods, the series publishes historical works that explore all aspects of the war, biographies of leading commanders, and tactical and campaign studies, along with select editions of primary sources. Together, these books shed new light on an era that remains central to our understanding of American and world history.

2019 David Silkenat

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Dead Mans Hand, Cutright, IM Fell English, and Scala Sans

by codeMantra, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Cover and pp. i, iii, and ix: Julian Scott, Surrender of a Confederate Soldier, 1873, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Nan Altmayer, 2012.23. Image courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum/Wikimedia Commons

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Silkenat, David, author.

Title: Raising the white flag : how surrender defined the American Civil War / by David Silkenat.

Other titles: Civil War America (Series)

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Series: Civil War America | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018031110 | ISBN 9781469649726 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469649733 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865. | Capitulations, MilitaryUnited StatesHistory19th century. | Capitulations, MilitaryConfederate States of AmericaHistory. | Capitulations, MilitarySocial aspects.

Classification: LCCE468.9 .S56 2019 | DDC 973.7dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018031110

Contents

Illustrations

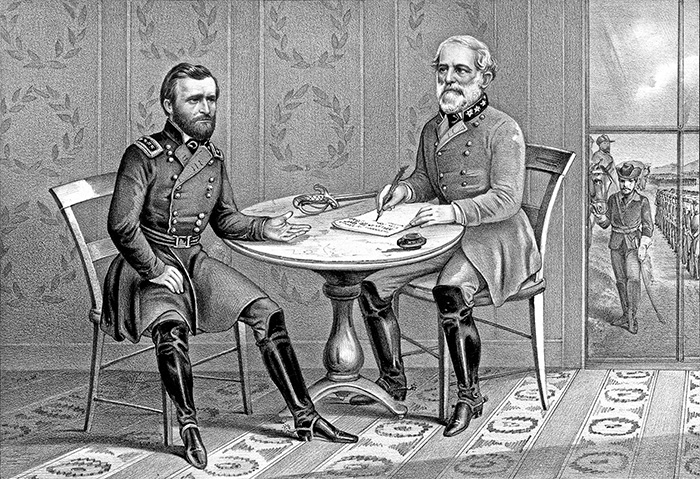

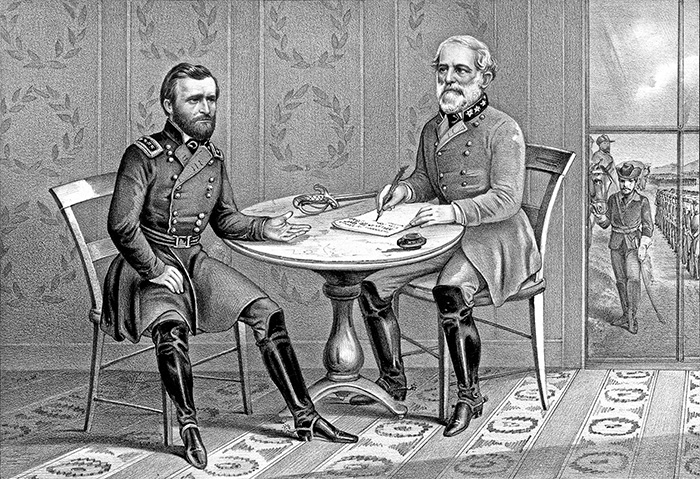

FIGURE 1. Currier & Ives, Surrender of General Lee at Appomattox, C.H. Va. April 9th 1865

FIGURE 2. Alfred Waud, Robert E. Lee leaving the McLean House following his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant

Raising the White Flag

FIGURE 1. Currier & Ives, Surrender of General Lee at Appomattox, C.H. Va. April9th 1865 (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-09914)

Introduction

Shortly after Confederate general Robert E. Lees surrender to Union general Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, New York printmakers Currier & Ives produced one of the first artistic representations of the scene. Issuing the lithograph in several different versions, in both color and black and white, Currier & Ives depicted the event as many would have envisioned it: the two men alone, seated across the table from each other, Lee writing the terms of the surrender, his sword resting between them on the table, while Grant waits for Lee to finish, his hand outstretched. Unfortunately, the illustrators got nearly everything in their depiction wrong. Lee and Grant sat at separate tables, and the dcor bears little resemblance to that in the McLean parlor, which, unlike the image, did not feature olive branch wallpaper. Lee had an aide with him, while Grant had more than a dozen members of his staff present. Grant wrote the original terms of surrender, to which Lee only made minor modifications.

Despite the images gross inaccuracies, it captured something of surrenders paradoxical nature. The two men appear as equals in the picture, mirroring each other at the table. Yet it was their radical inequality that prompted the meeting at Appomattox Courthouse. Lees army was surrounded, broken, and outnumbered. His men, some of whom had not eaten in days, could barely march. The image demonstrates none of these inequalities; indeed, if one did not know which man was the victor and which the vanquished, it would be impossible to tell from the image. In this respect, the Currier & Ives lithograph found itself in good company. Artistic depictions of Civil War surrender, those made both during and after the conflict, often created a visual equivalency between those surrendering and those accepting the surrender. They relied on the viewer to provide the subtext.

Surrenders present anomalous moments in times of war, a hiatus from bloodshed and death in favor of negotiation and compromise. They require

The American Civil War began with a surrender and ended with a series of surrenders, most famously at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia, but also at Bennett Place, North Carolina, at Citronelle, Alabama, and at Jacksonport, Arkansas, among other sites. Between Fort Sumter and Appomattox Courthouse, both Union and Confederate forces surrendered on dozens of occasions. Some of these surrenders are well known: Fort Donelson, Harpers Ferry, and Vicksburg among them. Many others, such as the Union surrender at San Augustin Springs in the New Mexico Territory in 1861 or the Confederate surrender on Roanoke Island in 1862, linger in relative obscurity. In the largest of these surrenders, soldiers numbering in the thousands laid down their arms. While the surrender of entire armies, such as at Vicksburg or Appomattox Courthouse, presented surrender in its most formal scale, in nearly every Civil War battle, soldiers found themselves in a position where choosing not to fight appeared to be their only option. At its smallest scale, individual soldiers, often because of injury or surprise, often surrendered. In between these extremes, Civil War soldiers surrendered at every level of military organization.

One of every four Civil War soldiers surrendered at some point during the conflict, making it one of the most common military experiences. Although the statistics are woefully incomplete, more than 673,000 soldiers surrendered during the American Civil War, including at least 211,000 Union and 462,000 Confederate soldiers. Formal surrenders, such as Vicksburg, Appomattox Courthouse, or Bennett Place, account for approximately half of this figure. Battlefield surrenders, when individual soldiers threw down their weapons and raised their hands in surrender, make up the remainder. To put these figures in context, the number of soldiers who surrendered during the Civil War is approximately equal to the number of soldiers killed. If death shaped the Civil War, so too did surrender.

Against this background, the Civil War presents a startling contrast. Americans, Northerners and Southerners alike, frequently surrendered, usually without stigma. Indeed, Maj. Robert Anderson became a celebrated national hero for his surrender at Fort Sumter, and Robert E. Lees stature only grew after Appomattox Courthouse. This book seeks to make sense of the anomalous place of surrender during the Civil War and to understand how Americans during the Civil War era understood surrender. It argues that American ideas about surrender at the beginning of the Civil War grew out of inherited notions that surrender helped to distinguish civilized warfare from barbarism. Although one could honorably surrender, dishonor and humiliation always loomed in the periphery and could be avoided only through carefully evaluating whom one surrendered to and whom one allowed to surrender and under what conditions. This initial conception of surrender, present at the time of Fort Sumter, evolved over the course of the Civil War. Demands for unconditional surrender, the enlistment of black men into the Union Army, the proliferation of guerilla warfare, and what some historians have termed hard warfare all challenged the meaning of surrender in the minds of soldiers, civilians, and politicians. In the final phase of the war, when Confederate defeat became inevitable, surrender became the route to peace, albeit a difficult and perilous one. In the 150 years since the wars end, Southerners and Northerners alike have struggled about how best to remember and commemorate surrenders. Unlike battlefields, where coherent patterns of commemoration decorated the landscape, surrender sites have demonstrated the difficulties Americans have had in making sense of surrender.

Next page