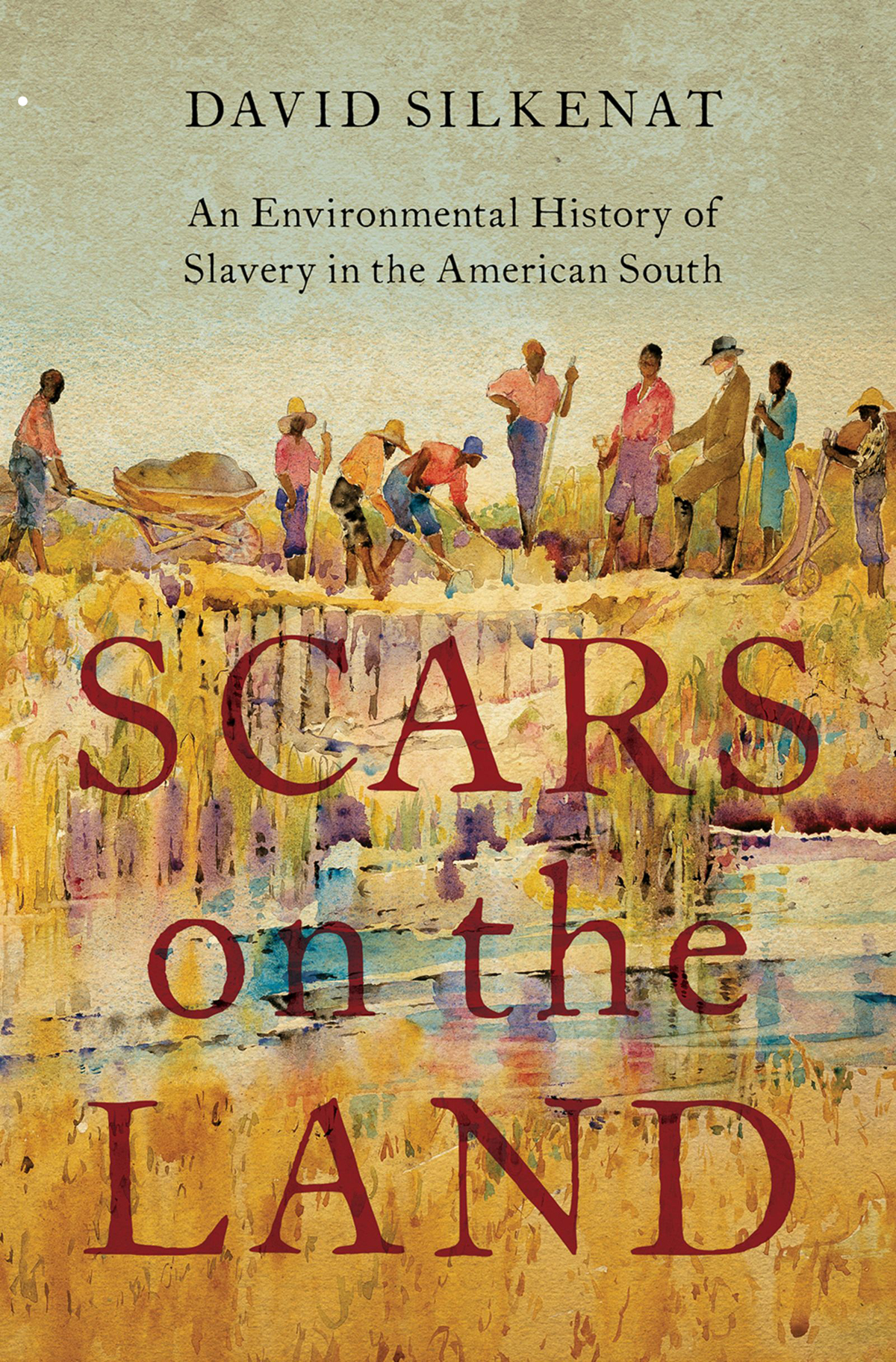

David Silkenat - Scars on the Land

Here you can read online David Silkenat - Scars on the Land full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: OxfordUP, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Scars on the Land

- Author:

- Publisher:OxfordUP

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Scars on the Land: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Scars on the Land" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Scars on the Land — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Scars on the Land" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197564226

eISBN 9780197564240

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197564226.001.0001

In enumerating the many barriers to freedom, Anderson lumped together natural and human obstacles. He understood that slaverys shackles were not just man-made; enslaved people toiled in an environment that conspired with slave owners to keep African Americans in bondage. At the same time, Anderson and other enslaved people knew the Southern environment in a way their enslavers never could. By day, they plucked worms from tobacco leaves, trod barefoot in the mud as they hoed rice fields, and felt the late summer sun on their backs as they picked cotton. By night, they clandestinely took to the woods and swamps to trap opossums and turtles, to visit relatives living on adjacent plantations, and to escape to freedom.

While the Southern environment provided the context for the peculiar institution, enslaved labor remade the landscape. One simple calculation had profound consequences: rather than measuring productivity based on outputs per acre, Southern planters sought to maximize how much labor they could extract from their enslaved workforce. They saw the landscape as disposable, relocating to more fertile prospects once they had leached the soils and cut down the forests. The expanding enslaved frontier irrevocably transformed the environment. On its leading edge, slavery laid waste to fragile ecosystems, draining swamps and clearing forests to plant crops and fuel steamships. On its trailing edge, slavery left eroded hillsides, rivers clogged with sterile soil, and the extinction of native species. Although the precise mechanisms and effects varied in Virginias tobacco fields, Louisianas swamps, and North Carolinas pine forests, slavery exacted the same swift price. While environmental destruction fueled slaverys expansion, no environment could long survive intensive slave labor. The scars manifested themselves in different ways, but the land too fell victim to the slave owners lash.

Slavery more than nature defined the South as a region. Geographers have identified dozens of distinct ecosystems within the American South, encompassing a vast variety of soil types, weather patterns, and biota. Two centuries of human bondage cemented these diverse biomes into a distinct cultural region. When they sought to establish a slaveholders republic in 1861, Southern partisans saw enslaved labor as the thread that linked the Eastern Coastal Plain, the Appalachian Piedmont, and the Mississippi Delta. The South is now in the formation of a Slave Republic, wrote L. W. Spratt, the editor of the Charleston Mercury, in February 1861. Its commitment to human bondage defined the South as a geographical section and provided what Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens described as the cornerstone of the new republic. Its advocates championed the Souths ecological diversity as an asset, one that enslaved labor could exploit. What a soil, and climate, and variety of productions, boasted Daniel M. Barringer in April 1861, shortly after the firing on Fort Sumter. Urging his fellow North Carolinians to join the newly established Southern Confederacy, Barringer saw its future in the expanding slave frontier, where almost everywhere an inviting soil, capable of every variety of production and, in many portions of the Confederacy, still of virgin fertilitywith every good climate of the world, and very little of the bad. For Spratt, Stephens, Barringer, and other Confederate nationalists, slavery undergirded the world they hoped to defend. As historian Ira Berlin has observed, the ethos of a slave society infused and infected all aspects of its social order: law, family, custom, religion, politics, and art. Slavery also shaped how white and Black Southerners came to view the land itself and their relationship to it.

This book begins from a simple premise: between 1665 and 1865 the environment fundamentally shaped American slavery, and slavery remade the Southern landscape. The complex interplay between slavery and the environment in the American South over two centuries does not lend itself to easy or straightforward narratives. Each of this books first six chapters adopts a feature of the Southern landscape as a vehicle for understanding how the environment shaped the lives of enslaved people and how they shaped their environment: soil, animals, trees, rivers, weather, and swamps. Although treated separately, these facets naturally intersect in intricate and powerful ways, as the environmental effects of enslaved labor cascaded throughout the ecosystem. The final chapter examines how the environmental factors during the Civil War shaped emancipation, demonstrating how African Americans drew upon accumulated environmental knowledge to liberate themselves. This thematic approach does not purport to provide an exhaustive or encyclopedic account, but rather to create a framework for understanding the relationship between slavery and the environment for others to expand upon, improve, and challenge.

To some degree, historians of American slavery have always recognized that environmental conditions mattered. In 1929, Ulrich B. Phillips opened his Life and Labor in the Old South by noting, Let us begin by discussing the weather, for that has been the chief agency in making the South distinctive. If not for the climate, Philips argued, plantation agriculture and thus slavery would never have developed. Historians also recognized that enslaved labor reshaped the landscape. Beginning with

This study draws upon some familiar sources such as fugitive slave narratives that recounted not only the horrors of human bondage but also how the Southern landscape shaped the contours of their enslavement. The particular demands of Virginias tobacco fields, South Carolinas rice marshes, and the Black Belts cotton plantations defined how slaves labored, each environment exacting a particular type of torture on the enslaved body and soul. The Southern landscape also determined their routes of escape. In evading slave patrols, fugitives hid in loblolly forests, pocosin swamps, alligator-infested rivers, and Smoky Mountain caves. Formerly enslaved people recalled their memories of these experiences and recounted them in WPA interviews conducted in the late 1930s. More than six decades after emancipation, elderly men and women vividly described how the soil, the weather, and the wilderness defined and confined their early lives.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Scars on the Land»

Look at similar books to Scars on the Land. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Scars on the Land and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.