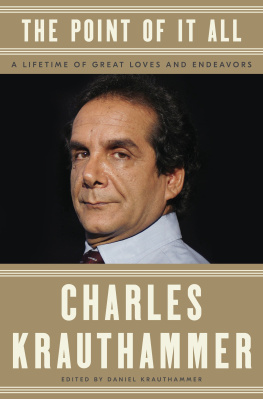

I. The Author and the Editor of This Book

Charles Krauthammer was my father. Writing that sentence in the past tense is still a shock to me, and it evokes a sadness far too deep to express in words. My father and I were very close. I feel the pain of his absence every day, as does every son who loved his father. There were a thousand secret private things between him and me that I alone had known and that I alone will miss about the man who was my dad.

But my father belonged not only to me, but to so many more: his friends, his colleagues, his readers, his viewers, the country and indeed the world. He played a large role in the political life of this nation, and though he was far too self-effacing to say so himself, his thinking, his ideas and his convictions shaped generations of political thinkers.

For almost four decades, he wrote a weekly column syndicated in the Washington Post and hundreds of other newspapers around the world. He wrote essays for preeminent magazines like The New Republic,Time and The Weekly Standard. He appeared on television to comment on the events of the day throughout his career, culminating with near-nightly appearances on Fox News Special Report for over a decade.

Policymakers and politicians in Washington read him, listened to him and often took their lead from him. But my father did not write solely for the cognoscenti and the power brokers. He always told me that he wanted to write and speak so that anyone with intelligence and interest could grapple with and benefit from his arguments. He believed in Einsteins (apocryphal) dictum that if you cant explain it simply, you dont understand it well enough. That, I believe, is the root of his extraordinary popularity. He didnt talk down. He thought that unnecessary complexity and heavy-handed erudition got in the way of true insight and knowledge: You dont want to talk in highfalutin, ridiculous abstractions that nobody understands, he said. Just try to make things plain and clear. He wished to express the truths he saw in the most universal, accessible, concise and convincing way that he could.

He felt a responsibility to his readers and viewers and, beyond that, to history itself. As he put it:

I left psychiatry to start writingbecause I felt history happening outside the examining-room door. That history was being shaped by a war of ideas and I wanted to be in the arena. Not for its own sake. I enjoy intellectual combat, but I dont live for it. I wanted to be in the arena because some things matter, some things need to be said, some things need to be defended.

My father was not just going through the motions. He cared deeply about everything he said and everything he wrote. He knew it would play a part in the discourses that shaped real policies, affected real people and determined the future of the country he loved. He did not take that responsibility lightly. In a 2013 interview, he described the sense of duty he felt to pursue his vocation with the highest order of integrity: Youre betraying your whole life if you dont say what you thinkand you dont say it honestly and bluntly.

He always said what he thought, and he championed the ideas he believed in. That is why he will be missed by everyone who appreciated his arguments and insights. And that is why it was so important to me to complete this book for him, and to complete it well. His thoughts mattered. His arguments mattered. His presence in our national discourse mattered. And I hope, through this book, they will continue to matter for future generations of readers.

II. The Origins of This Book

This book was a long time in the making. Following the success of his lauded collection of columns and essays Things That Matter, my father had intended to write several more books. He wished to write an original work on foreign policy, another on domestic policy and a more personal memoir that would trace his family history as well as his own. But in addition to these ambitions for new writing projects, he felt an ever-present desire to publish another collection. There were many more columns and essays of his that he wanted the world to see. Pieces that had not fit with the thematic organization of Things That Matter, pieces he had written in the time since and pieces that, frankly, he had felt were too personal to include the first time around. These columns and essays needed a home.

In 2016, my father decided he would move ahead simultaneously toward completion of that new collection and an original work on foreign policy. He put together an initial selection of columns and began organizing them into thematic chapters. Meanwhile, he began writing an extended essay for the work on foreign policy and collecting pieces he planned to draw on in composing the other entries for that book.

It was at this juncture that a health crisis struck my father. In August of 2017, he underwent surgery in Washington, DC, to remove a cancerous tumor from his abdomen. The surgery was thought to have been a success in removing the cancer, but a cascade of secondary complications followed. My father spent many months in the ICU and then many more at a specialized catastrophic care hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. Great progress was made in the following months toward restoring him to health. There were extraordinary difficulties and many setbacks, but the light at the end of the tunnel was clearly visible and we were slowly making our way.

Though his energies were intensely focused on his physical recovery, my father devoted what time and attention he could while he was in the hospital to working on the book. My mother and I were by his side for the entire ten months of that hospital sojourn. During that time I concocted an array of digital and physical displays of all shapes and sizes (with assistance from our favorite hospital staff friends, who helped me rewire our TVs and commandeer the buildings wi-fi) to build as practical a workplace for him as we could achieve amongst all the medical gadgets and gizmos. These helter-skelter arrangements worked well enough for my father to get by, and there were times when we were able to talk over his plans and ideas together and I could help him execute some of the details.