ASIA PACIFIC MODERN

Takashi Fujitani, Series Editor

Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times , by Miriam Silverberg

Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific , by Shu-mei Shih

The Politics of Gender in Colonial Korea: Education, Labor, and Health, 1910-1945 , by Theodore Jun Yoo

Frontier Constitutions: Christianity and Colonial Empire in the Nineteenth-Century Philippines , by John D. Blanco

Tropics of Savagery: The Culture of Japanese Empire in Comparative Frame , by Robert Thomas Tierney

Colonial Project, National Game: A History of Baseball in Taiwan , by Andrew D. Morris

Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II , by T. Fujitani

The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China's Collective Past , by Gail Hershatter

A Passion for Facts: Social Surveys and the Construction of the Chinese Nation-State, 1900-1949 , by Tong Lam

Imaging Disaster: Tokyo and the Visual Culture of Japan's Great Earthquake of 1923 , by Gennifer Weisenfeld

Redacted: The Archives of Censorship in Transwar Japan , by Jonathan E. Abel

Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 , by Todd A. Henry

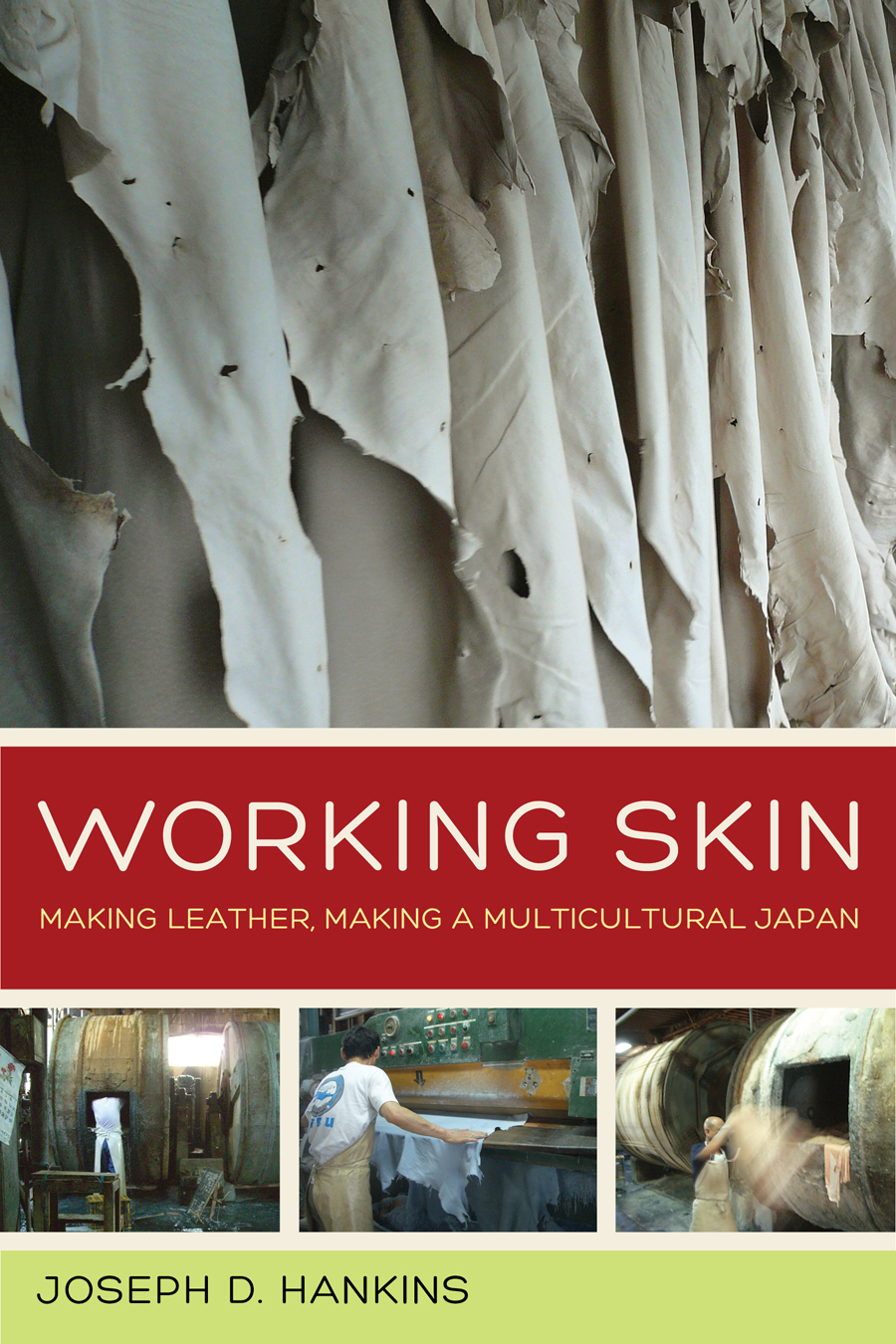

Working Skin: Making Leather, Making a Multicultural Japan , by Joseph D. Hankins

Working Skin

MAKING LEATHER, MAKING A MULTICULTURAL JAPAN

Joseph D. Hankins

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2014 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hankins, Joseph D.

Working skin: making leather, making a multicultural Japan / Joseph D. Hankins.

pages cm. (Asia Pacific modern; 13)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-28328-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-520-28329-9 (pbk.: alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-520-95916-3

1. Buraku peopleSocial conditions. 2. Buraku peopleGovernment policy. 3. MulticulturalismJapan. 4. LaborJapan. 5. Working classJapan. 6. JapanSocial conditions. 7. JapanPolitics and government. I. Title.

HT725.J3H255 2014

305.5680952dc23

2014005898

Manufactured in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Natural, a fiber that contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO z3948-1992 (R 1997) ( Permanence of Paper ).

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

Hailing from Texas

TEXAS IS AN OCCASIONAL but persistent part of the story this book tells. Much of the rawhide produced in West Texas in the last half of the twentieth century was sent to Japan to be processed into leather there. Chapter 2, Ushimatsu Left for Texas, touches on the ways in which Texas has lived in a Buraku imaginary as a place that values rather than stigmatizes human involvement in meat production. And, finally, I too am from West Texas and have been well served by that romantic imaginary in conducting my research on the leather industry in Japan.

To begin this book I would like to relate a story explaining how I came to this project, an account more personal than a similar examination that happens in the conclusion. My reasons and motivations for engaging in this research are more diffuse, contingent, and motivated than this one story might indicate. However, this story serves as a convenient shorthand to open the central issues of my research.

When I entered my PhD program in anthropology in 2001, I intended to research language use, gender, and sexuality in Japan. In my second year I moved from Chicago to Yokohama for language study and had the good fortune of joining a Minority Research Group at the University of Tokyo. Led by sociology professor Fukuoka Yasunori, this group met monthly to discuss the research of graduate students and faculty working on minority-related projects. After a few months, Fukuoka invited me to accompany him and a handful of his students to a leather tannery in Tochigi Prefecture, north of Tokyo, to tour the facility and conduct interviews over a weekend. It was to be a brief study tour of Buraku-related issues. At that time I was aware of Buraku issues. I knew they were a group of stigmatized people in Japan, but I thought of myself as studying something very different. However, one of my advisers in graduate school, Danilyn Rutherford, had repeatedly stressed the methodological value of accepting all invitations. In that spirit, I headed north with Fukuoka and a handful of his students.

FIGURE 1. Cattle in a feedlot outside of Lubbock, Texas.

When we arrived at the tannery in Tochigi, we were ushered into the main office to meet with the owner and manager. We went around the room introducing ourselves, and I could sense the curiosity building as my turn approached. Who was this obvious foreignerwhite, redheaded, and six foot twoand why was he present? When my turn came, I introduced myself to the group as a graduate student in anthropology from the University of Chicago, and also as a native of Lubbock, Texas. At that point the manager of the tannery stopped me and said, Lubbock? It's flat and dry and ugly there. While that is arguably the case, I was surprised that these men from a small town north of Tokyo would be at all familiar with an equally sized town in West Texas. I responded, Well, yes, Lubbock is flat and dry and ugly, but how do you know that?

It turned out that the majority of the rawhide used at this tannery came, in salted crates, from my hometown, shipped through Los Angeles to Tokyo and then up by train to Tochigi, to be tanned into leather there, 7,000 miles away from where it had started. A small group of the tannery management had traveled to Lubbock several years prior to tour ranches, feedlots, and slaughterhouses in the Texas Panhandle; they knew Lubbock was flat, dry, and ugly because they had been there. I was stunned by this information. Growing up in Lubbock, I had always been aware that the ranching and meat processing industry was largeanyone with a working nose is aware of the cattle, and the ranching heritage center around the corner from my house was a frequent destination on school field tripsbut I had not anticipated that parts of the cattle in the feedlots outside my hometown, feedlots where high school friends of mine worked, might end up on the other side of the planet where I too then lived.

I typically narrate this moment as one of epiphany, a paradigm shift for my project: I decided to take contingency as a sign of providence, discard an examination of language use and gender, and instead take up a study of Buraku issues as they connected to global commodity circuits reaching as far back as Lubbock, Texas. Providence, however, is a gloss that deserves some unpacking; the ethical and political impulses it encompasses are deeply entangled with the ethical impulses that are part of the subject matter of this book.