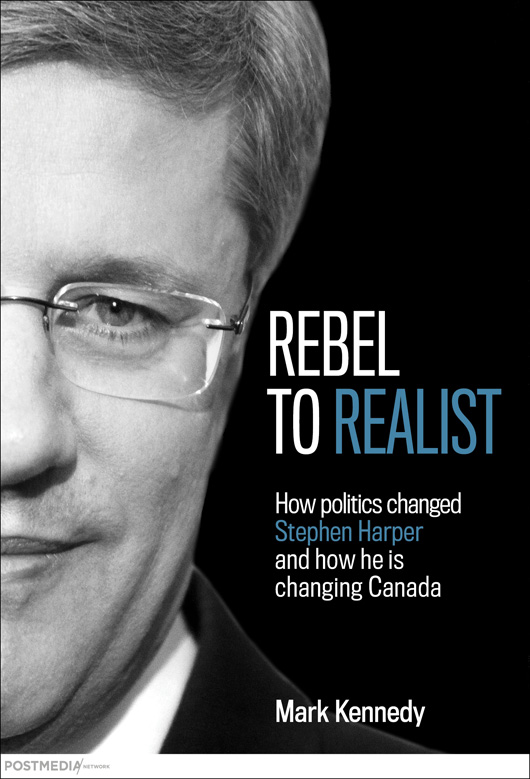

Mark Kennedy of Postmedia News, centre, speaks with Prime Minister Stephen Harper in his Parliament Hill office in February 2012. Ashley Fraser/ Postmedia News

It began with a tweet, at 9:44 a.m. on Jan. 28, 2013, as Canadas MPs returned to the House of Commons following a six-week break.

Had breakfast with Stanley.

Stanley, as the Twitter photo made clear, was a cat lazing on a kitchen chair.

But this was no ordinary cat. The tweet apparently had come from Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who was sitting next to the family pet, eating breakfast.

From there, the tweets continued: an avalanche of pixels and Twitter microbursts. Photos and videos of Harper leaving for the office; working and eating at his desk; speaking in the House of Commons; meeting war veterans; returning home to be greeted by wife Laureen and the familys pet chinchilla, Charlie; then working at his laptop late into the evening.

A day in the life of Stephen Harper, via Twitter. Twenty-eight tweets posted over nearly 12 hours. It generated the media buzz Harpers handlers had hoped for, despite the blatant superficiality.

Yet Harper is far from superficial. Throughout the 25 years in which I have covered federal politics a span that has included five prime ministers I have found he is the hardest to describe.

Principled yet pragmatic. Tough yet compassionate. Self-assured yet shy. Brilliant yet prone to mistakes. Its difficult to label him, in part because he has constantly changed over the past quarter-century.

In recent months, I set out to explore that evolution, interviewing dozens of people who know him well.

How could a man who was once so clear in his conservative principles become so politically pragmatic? Why did he decide to govern so cautiously?

And after seven years in power, how has Harpers Conservative government changed Canada?

I first wrote about Harper on Aug. 20, 1992, when he was the Reform partys 33-year-old chief policy officer, fighting to reform the Senate. He was defiant. Resolute. Even strident.

Two decades later, he was prime minister and I was covering him almost daily in Parliament, on the hustings, and on many of his foreign trips.

I have been fortunate enough to interview him several times usually in his parliamentary office, and once on his campaign jet. Notwithstanding his obvious wariness of the media, I generally found him to be more co-operative than his reputation would suggest. Ask Stephen Harper a straight-up question and you generally get a direct, often thoughtful, answer.

It was just that way one memorable afternoon, Jan. 12, 2011, when I interviewed him in his office across from Parliament Hill. He sat casually in a black leather chair, the Peace Tower visible in the window frame behind him, as we discussed everything from the economy to health care to public subsidies for political parties.

Harper was approaching his five-year anniversary in power, so I asked him what he had learned and what he thought of criticism that he was too controlling as prime minister.

Ive only ever heard two criticisms of prime ministers, he replied. Theyre either too controlling or theyre not in control. Prime ministers who arent in control dont last very long.

And what did he learn? He said its important that every prime minister know where he or she wants to take the country as they start the job. They need to know which broad principle they will apply.

But his pragmatic side also surfaced. Things just change constantly and you do have to be adaptable, he said. When things change as rapidly as they do, you cant be locked in to the same answer in every situation.

Not something I thought I would hear from the former Reformer who once railed against deficits, big government and the unelected Senate. But on this day, Harper made no apologies.

Weve done a lot of things where weve made some compromises but in the vast majority of cases weve done them for the right reasons and theyve worked out well, he said.

Four months later, Harper won a majority government.

By mid-2013, however, some Canadians werent sure he was the politician they once thought they knew. Some of his compromises had caught up with him.

More than a quarter-century after Harper walked into our lives as a rising young star in the Reform party, its worth understanding where he has come from, how hes changed and how hes stayed the same. I hope this book sheds some light on that.

Mark Kennedy

Ottawa, August 2013

Stephen Harper, centre, has been described as a child who got along with everybody. Image courtesy of Dimitri Soudas

On the morning of Tuesday, May 21, 2013, Prime Minister Stephen Harper walked into Room 237-C at the heart of Parliament Hills Centre Block to speak to members of the Conservative caucus.

He was met with a standing ovation from the MPs and senators jammed inside, many anxiously hoping their leader would work his magic and make a political hurricane disappear.

Forty-eight hours earlier, Harper had reluctantly announced the resignation of his chief of staff, Nigel Wright, who had given $90,172 of his own money to Sen. Mike Duffy. The money was meant to repay Duffys ineligible Senate housing expenses, and those present at the caucus meeting expected some explanations.

For years, Harper long an advocate of Senate reform had promised never to appoint anyone to the Senate. Yet, by 2013, he had appointed dozens. On one day alone, he made 18 appointments including Duffy, former broadcaster Pamela Wallin, and aboriginal leader Patrick Brazeau.