The Violence of the

GREEN

REVOLUTION

The Violence of the

GREEN

REVOLUTION

Third World Agriculture, Ecology

and Politics

VANDANA SHIVA

Copyright 2016 by Vandana Shiva

Published by the University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State Uninversity, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 S. Limestone St., Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

ISBN 978-0-8131-6654-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6681-0 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-8131-6680-3 (epub)

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Members of the Association of

American University Presses. |

Contents

Acknowledgements

This study of the ecological and social costs of the Green Revolution and the links between the ecological and ethnic crisis in Punjab, began in 1986, as part of the major project on Conflicts Over Natural Resources of the Peace and Global Transformation programme of the United Nations University.

Support from the Third World Network made it possible to continue the study during 1987-89. I am grateful to Prof. Uppal and Prof. Sidhu, and to the many scientists of Punjab Agricultural University in Ludhiana without whose inputs and cooperation, this study would not have been possible.

Anjali Kalgutkar has helped with maps and illustrations. The Third World Network secretariat especially Chee Yoke Heong, Christina Lim and Lim Jee Yuan, has taken care of all the details of the final editing and production of this book. I thank them for all of their contributions.

To Dr. Richaria,

for a lifetime of struggle to keep

peoples agriculture knowledge alive.

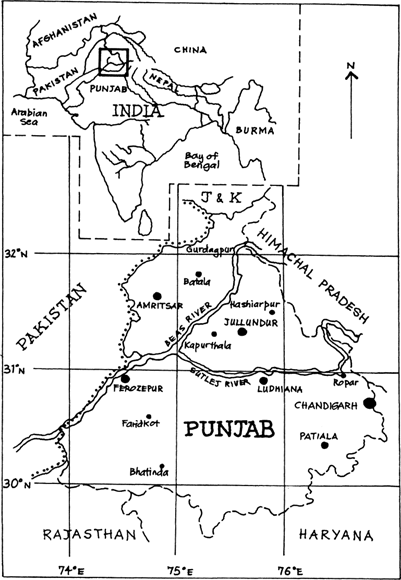

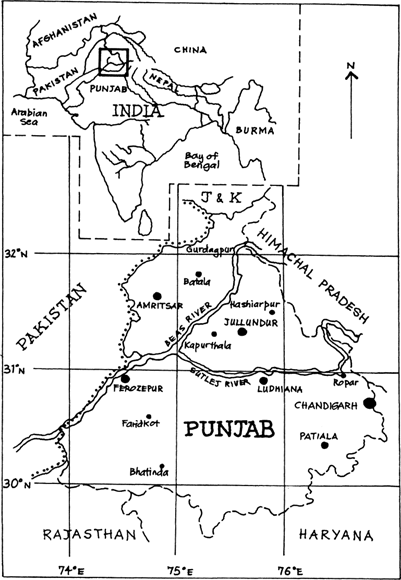

Study area location within the Indian Union

Source: Kang, 1982

INTRODUCTION

TWO MAJOR crises have emerged on an unprecedented scale in Asian societies during the 1980s. The first is the ecological crisis and the threat to life support systems posed by the destruction of natural resources like forests, land, water and genetic resources. The second is the cultural and ethnic crisis and the erosion of social structures that make cultural diversity and plurality possible as a democratic reality in a decentralised framework. The two crises are usually viewed as independent, both analytically as well as at the level of political action.

The tragedy of Punjab of the thousands of innocent victims of violence over the past few years has commonly been presented as an outcome of ethnic and communal conflict between two religious groups. This study presents a different aspect and interpretation of the Punjab tragedy. It introduces dimensions that have been neglected or gone unnoticed in understanding the emergent conflicts. It traces the conflicts and violence in contemporary Punjab to the ecological and political demands of the Green Revolution as an experiment in development and agricultural transformation. The Green Revolution has been heralded as a political and technological achievement, unprecedented in human history. It was designed as a techno-political strategy for peace, through the creation of abundance by breaking out of natures limits and variabilities. Paradoxically, two decades of the Green Revolution have left Punjab ravaged by violence and ecological scarcity. Instead of abundance, Punjab has been left with diseased soils, pest-infested crops, waterlogged deserts, and indebted and discontented farmers. Instead of peace, Punjab has inherited conflict and violence. 3,000 people were killed in Punjab during 1988. In 1987 the number was 1,544. In 1986, 598 people were killed.

The Punjab crisis is in large measure the tragic outcome of a resource intensive and politically and economically centralized experiment with food production. The experiment has failed even though the Green Revolution miracle continues to be advertised on every platform of every agency that stood to gain from it, the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, the World Bank, the seed and chemical multinationals, the Government of India and the various agencies it controls.

It is misleading to reduce the roots of communal conflict to religion, as most scholars and commentators have done, since the conflicts are also economic and political. They are not merely conflicts between two religious communities, but reflect cultural and social breakdown and tensions between a disillusioned farming community and a centralising state, which controls agricultural policy, finance, credit, inputs and prices of agricultural commodities. At the heart of these conflicts and disillusionments lies the Green Revolution. The present essay presents the other side of the Green Revolution story its social and ecological costs hidden and hitherto unnoticed. In so doing, it also offers a different perspective on the multiple roots of ethnic and political violence. It illustrates that ecological and ethnic fragmentation and breakdown are intimately connected and are an intrinsic part of a policy of planned destruction of diversity in nature and culture to create the uniformity demanded by centralised management systems.

This book is also an attempt to understand the paradox that is todays Punjab. Statistics show Punjab to be Indias most prosperous state, a model to which other regions and other countries aspire. Punjabs estimated gross domestic product per person was Rs2,528. The average per capita GDP for India was Rs1,334. The income of the average Punjabi was 65% greater than that of the average Indian.

According to the 1981 census, Punjabs population was 16.7 million, a little less than 2.5% of Indias population. Yet Punjab produces 7% of the countrys foodgrains, has 10% of Indias TV sets and 17% of Indias tractors. It has three times more roads per square kilometer. An average Punjabi uses twice as much energy per hour than an average Indian and three times as such fertilizer per hectare. Compared to 28% of the national average 80% of Punjabs 50,400 square kilometers of land are irrigated. The average Punjabi has twice as much money in the bank as the average Indian. On all conventional indicators of progress and development, Punjab has done better than the rest of India.

Yet Punjab is also the region most seething with discontent, with a sense of having been exploited and treated with discrimination. The sense of grievance runs so high that it has led to the largest numbers of killings in peacetime in independent India. At least 15,000 people have lost their lives in Punjab violence in the last six years.

Next page